W.J. Astore

“[W]ar is a distressing, ghastly, harrowing, horrific, fearsome and deplorable business. How can its actual awfulness be described to anyone?” Stuart Hills, By Tank Into Normandy, p. 244

“[E]very generation is doomed to fight its war, to endure the same old experiences, suffer the loss of the same old illusions, and learn the same old lessons on its own.” Philip Caputo, A Rumor of War, p. 81

The persistence of war is a remarkable thing. Two of the better books about war and its persistence are J. Glenn Gray’s “The Warriors” and Chris Hedges “War Is a Force that Gives Us Meaning.” Hedges, for example, writes about “the plague of nationalism,” our willingness to subsume our own identities in the service of an abstract “state” as well as our eagerness to serve that state by killing “them,” some “other” group that the state has vilified.

In warning us about the perils of nationalism, Hedges quotes Primo Levi’s words: “I cannot tolerate the fact that a man should be judged not for what he is but because of the group to which he belongs.” Levi’s lack of tolerance stems from the hardest of personal experiences: surviving Auschwitz as an Italian Jew during the Holocaust.

Gray takes this analysis in a different direction when he notes that those who most eagerly and bloodthirstily denounce “them,” the enemy, are typically far behind the battle lines or even safely at home. The troops who fight on the front lines more commonly feel a sort of grudging respect for the enemy, even a sense of kinship that comes with sharing danger in common.

Part of the persistence of war, in other words, stems from the ignorant passions of those who most eagerly seek it and trumpet its heroic wonders even as they stand (and strive to remain) safely on the sidelines.

Both Hedges and Gray also speak to the dangerous allure of war, its spectacle, its excitement, its awesomeness. Even the most visceral and “realistic” war films, like the first thirty minutes of “Saving Private Ryan,” represent war as a dramatic spectacle. War films tend to glamorize combat (think of “Apocalypse Now,” for example), which is why they do so little to put an end to war.

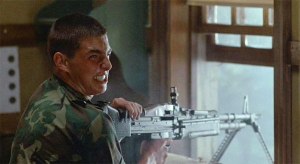

One of the best films to capture the dangerous allure of war to youth is “Taps.” I recall seeing it in 1981 at the impressionable age of eighteen. There’s a tiny gem of a scene near the end of the film when the gung ho honor guard commander, played by Tom Cruise before he was TOM CRUISE, mans a machine gun. He’s firing against American troops sent to put down a revolt at a military academy, but Cruise’s character doesn’t care who he’s firing at. He’s caught in the rapture of destruction.

He shouts, “It’s beautiful, man. Beautiful.” And then he himself is shot dead.

This small scene with Cruise going wild with the machine gun captures the adrenaline rush, that berserker capacity latent in us, which acts as an accelerant to the flames of war.

War continues to fascinate us, excite us. It taps primal roots of power and fear and ecstasy all balled together. It masters us, hence its persistence.

If and when we master ourselves, perhaps then we’ll finally put an end to war.