W.J. Astore

Twenty years ago, I left the Air Force Academy in Colorado Springs for my next assignment. I haven’t been back since, but today I travel there (if only in my imagination) to give my graduation address to the class of 2022. So, won’t you take a few minutes and join me, as well as the corps of cadets, in Falcon Stadium?

Congratulations to all you newly minted second lieutenants! As a former military professor who, for six years, taught cadets very much like you at the Academy, I salute you and your accomplishments. You’ve weathered a demanding curriculum, far too many room and uniform inspections, parades, restrictions, and everything else associated with a military that thrives on busywork and enforced conformity. You’ve emerged from all of that today as America’s newest officers, part of what recent commanders-in-chief like to call “the finest fighting force” in human history. Merely for the act of donning a uniform and taking the oath of office, many of your fellow Americans already think of you as heroes deserving of a hearty “thank you for your service” and unqualified expressions of “support.”

And I must say you do exude health, youth, and enthusiasm, as well as a feeling that you’re about to graduate to better things, like pilot training or intelligence school, among so many other Air Force specialties. Some of you will even join America’s newest service, the Space Force, which resonates with me, as my first assignment in 1985 was to Air Force Space Command.

In my initial three years in the service, I tested the computer software the Air Force used back then to keep track of all objects in earth orbit, an inglorious but necessary task. I also worked on war games in Cheyenne Mountain, America’s ultimate command center for its nuclear defense. You could say I was paid to think about the unthinkable, the end of civilization as we know it due to nuclear Armageddon. That was near the tail end of the Cold War with the Soviet Union. So much has changed since I wore gold bars like you and yet, somehow, we find ourselves once again in another “cold war” with Russia, this time centered on an all-too-hot war in Ukraine, a former Soviet republic, instead of, as in 1962, a country in our immediate neighborhood, Cuba. Still, that distant conflict is only raising fresh fears of a nuclear nightmare that could well destroy us all.

What does this old light colonel, who’s been retired for almost as long as he wore the uniform, have to teach you cadets so many years later? What can I tell you that you haven’t heard before in all the classes you’ve attended and all the lectures you’ve endured?

How about this: You’ve been lied to big time while you’ve been here at the Academy.

Ah, I see I have your attention now. More than a few of you are smiling. I used to joke with cadets about how four years at a military school were designed to smother idealism and encourage cynicism, or so it sometimes seemed. Yes, our lead core value may still be “integrity first,” but the brass, the senior leadership, often convinces itself that what really comes first is the Air Force itself, an ideal of “service” that, I think you’ll agree, is far from selfless.

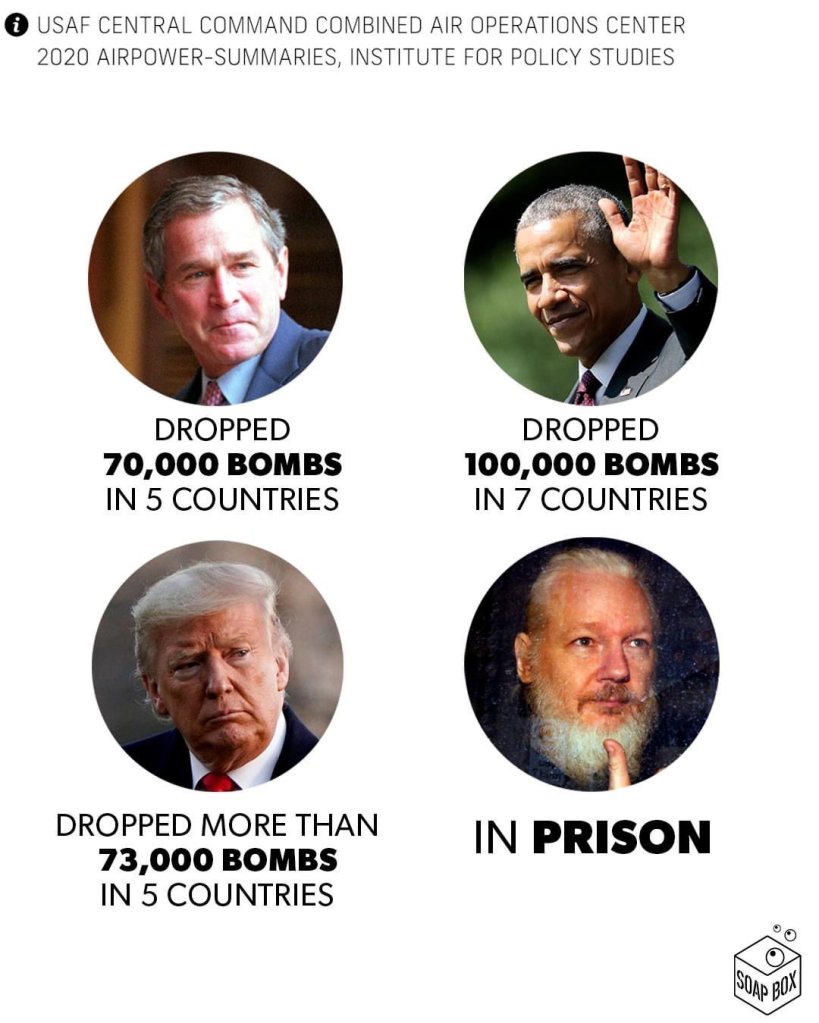

What do I mean when I say you’ve been lied to while being taught the glorious history of the U.S. Air Force? Since World War II began, the air forces of the United States have killed millions of people around the world. And yet here’s the strange thing: we can’t even say that we’ve clearly won a war since the “Greatest Generation” earned its wings in the 1930s and 1940s. In short, boasts to the contrary, airpower has proven to be neither cheap, surgical, nor decisive. You see what I mean about lies now, I hope.

I know, I know. You’re not supposed to think this way. You eat in Mitchell Hall, named after General Billy Mitchell, that airpower martyr who fought so hard after World War I for an independent air service. (His and our collective dream, long delayed, finally came to fruition in 1947.) You celebrate the Doolittle Raiders, those intrepid aviators who flew off an aircraft carrier in 1942, launching a daring and dangerous surprise attack on Tokyo, a raid that helped restore America’s sagging morale after Pearl Harbor. You mark the courage of the Tuskegee Airmen, those African American pilots who broke racial barriers, while proving their mettle in the skies over Nazi Germany. They are indeed worthy heroes to celebrate.

And yet shouldn’t we airmen also reflect on the bombing of Germany during World War II that killed roughly 600,000 civilians but didn’t prove crucial to the defeat of Adolf Hitler? (In fact, Soviet troops deserve the lion’s share of the credit there.) We should reflect on the firebombing of Tokyo that killed more than 100,000 people, among 60 other sites firebombed, and the atomic bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki that, both instantly and over time, killed an estimated 220,000 Japanese. During the Korean War, our air forces leveled North Korea and yet that war ended in a stalemate that persists to this day. During Vietnam, our air power pummeled Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia, unleashing high explosives, napalm, and poisons like Agent Orange against so many innocent people caught up in American rhetoric that the only good Communist was a dead one. Yet the Vietnamese version of Communism prevailed, even as the peoples of Southeast Asia still suffer and die from the torrent of destruction we rained down on them half a century ago.

Turning to more recent events, the U.S. military enjoyed total air supremacy in Afghanistan, Iraq, and other battlefields of the war on terror, yet that supremacy led to little but munitions expended, civilians killed, and wars lost. It led to tens of thousands of deaths by airpower, because, sadly, there are no such things as freedom bombs or liberty missiles.

If you haven’t thought about such matters already (though I’ll bet you have, at least a little), consider this: You are potentially a death-dealer. Indeed, if you become a nuclear launch officer in a silo in Wyoming or North Dakota, you may yet become a death-dealer of an almost unimaginable sort. Even if you “fly” a drone while sitting in a trailer thousands of miles from your target, you remain a death-dealer. Recall that the very last drone attack the U.S. launched in Afghanistan in 2021 killed 10 civilians, including seven children, and that no one in the chain of command was held accountable. There’s a very good reason, after all, why those drones, or, as we prefer to call them, remotely piloted aircraft, have over the years been given names like Predator and Reaper. Consider that a rare but refreshing burst of honesty.

I remember how “doolies,” or new cadets, had to memorize “knowledge” and recite it on command to upper-class cadets. Assuming that’s still a thing, here’s a phrase I’d like you to memorize and recite: Destroying the town is not saving it. The opposite sentiment emerged as an iconic and ironic catchphrase of the Vietnam War, after journalist Peter Arnett reported a U.S. major saying of devastated Ben Tre, “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.” Incredibly, the U.S. military came to believe, or at least to assert, that destroying such a town was a form of salvation from the alleged ideological evil of communism. But whether by bombs or bullets or fire, destruction is destruction. It should never be confused with salvation.

Will you have the moral courage, when it’s not strictly in defense of the U.S. Constitution to which you, once again, swore an oath today, to refuse to become a destroyer?

Two Unsung Heroes of the U.S. Air Force

In your four years here, you’ve learned a lot about heroes like Billy Mitchell and Lance Sijan, an Academy grad and Medal of Honor recipient who demonstrated enormous toughness and resilience after being shot down and captured in Vietnam. We like to showcase airmen like these, the true believers, the ones prepared to sacrifice everything, even their own lives, to advance what we hold dear. And they are indeed easy to respect.

I have two more courageous and sacrificial role models to introduce to you today. One you may have heard of; one you almost certainly haven’t. Let’s start with the latter. His name was James Robert “Cotton” Hildreth and he rose to the rank of major general in our service. As a lieutenant colonel in Vietnam, Cotton Hildreth and his wingman, flying A-1 Skyraiders, were given an order to drop napalm on a village that allegedly harbored enemy Viet Cong soldiers. Hildreth disobeyed that order, dropping his napalm outside the target area and saving (alas, only temporarily) the lives of 1,200 innocent villagers.

How could Hildreth have possibly disobeyed his “destroy the town” order? The answer: because he and his wingman took the time to look at the villagers they were assigned to kill. In their Skyraiders, they flew low and slow. Seeing nothing but apparently friendly people waving up at them, including children, they sensed that something was amiss. It turns out that they were oh-so-right. The man who wanted the village destroyed was ostensibly an American ally, a high-ranking South Vietnamese official. The village hadn’t paid its taxes to him, so he was using American airpower to exact his revenge and set an example for other villages that dared to deny his demands. By refusing to bomb and kill innocents, Hildreth passed his “gut check,” if you will, and his career doesn’t appear to have suffered for it.

But he himself did suffer. He spoke about his Vietnam experiences in an oral interview after he’d retired, saying they’d left him “really sick” and “very bitter.” In a melancholy, almost haunted, tone, he added, “I don’t talk about this [the war] very much,” and one can understand why.

So, what happened to the village that Hildreth and his wingman had spared from execution by napalm? Several days later, it was obliterated by U.S. pilots flying high and fast in F-105s, rather than low and slow as Hildreth had flown in his A-1. The South Vietnamese provincial official had gotten his way and Hildreth’s chain of command was complicit in the destruction of 1,200 people whose only crime was fighting a tax levy.

My second hero is not a general, not even an officer. He’s a former airman who’s currently behind bars, serving a 45-month sentence because he leaked the so-called drone papers, which revealed that our military’s drone strikes killed far more innocent civilians than enemy combatants in the war on terror. His name is Daniel Hale, and you should all know about him and reflect on his integrity and honorable service to our country.

What was his “crime”? He wanted the American people to know about their military and the innocent people being killed in our name. He felt the burden of the lies he was forced to shoulder, the civilians he watched dying on video monitors due to drone strikes. He wanted us to know, too, because he thought that if enough Americans knew, truly knew, we’d come together and put a stop to such atrocities. That was his crime.

Daniel Hale was an airman of tremendous moral courage. Before he was sentenced to prison, he wrote an eloquent and searing letter about what had moved him to share information that, in my view, was classified mainly to cover up murderous levels of incompetence. I urge you to read Hale’s letter in which he graphically describes the deaths of children and the trauma he experienced in coming to grips with what he termed “the undeniable cruelties that I perpetuated” while serving as an Air Force intelligence analyst.

It’s sobering stuff, but we airmen, you graduates in particular, deserve just such sobering information, because you’re going to be potential death-dealers. Yet it’s important that you not become indiscriminate murderers, even if you never see the people being vaporized by the bombs you drop and missiles you’ll launch with such profligacy.

In closing, do me one small favor before you throw your caps in the air, before the Thunderbirds roar overhead, before you clap yourselves on the back, before you head off to graduation parties and the congratulations of your friends and family. Think about a saying I learned from Spider-Man. Yes, I really do mean the comic-book hero. “With great power comes great responsibility.”

Like so many airmen before you, you may soon find yourself in possession of great power over life and death in wars and other conflicts that, at least so far in this century, have been all too grim. Are you really prepared for such a burden? Because power and authority, unchecked by morality and integrity, will lead you and our country down a very dark path indeed.

Always remember your oath, always aim high, the high of Hildreth and Hale, the high of those who remember that they are citizen-airmen in service to a nation founded on lofty ideals. Listen to your conscience, do the right thing, and you may yet earn the right to the thanks that so many Americans will so readily grant you just by virtue of wearing the uniform.

And if you’ll allow this aging airman one final wish: I wish you a world where the bombs stay in their aircraft, the missiles in their silos, the bullets in their guns, a world, dare I say it, where America is finally at peace.

Copyright 2022 William J. Astore. Originally at TomDispatch.com. Please read TomDispatch.com, a regular antidote to the mainstream media. Thank you!