W.J. Astore

Militarized Hype Obscures Deep Rot in the American Empire

Also at TomDispatch.com.

In his message to the troops prior to the July 4th weekend, Secretary of Defense Lloyd Austin offered high praise indeed. “We have the greatest fighting force in human history,” he tweeted, connecting that claim to the U.S. having patriots of all colors, creeds, and backgrounds “who bravely volunteer to defend our country and our values.”

As a retired Air Force lieutenant colonel from a working-class background who volunteered to serve more than four decades ago, who am I to argue with Austin? Shouldn’t I just bask in the glow of his praise for today’s troops, reflecting on my own honorable service near the end of what now must be thought of as the First Cold War?

Yet I confess to having doubts. I’ve heard it all before. The hype. The hyperbole. I still remember how, soon after the 9/11 attacks, President George W. Bush boasted that this country had “the greatest force for human liberation the world has ever known.” I also remember how, in a pep talk given to U.S. troops in Afghanistan in 2010, President Barack Obama declared them “the finest fighting force that the world has ever known.” And yet, 15 years ago at TomDispatch, I was already wondering when Americans had first become so proud of, and insistent upon, declaring our military the world’s absolute best, a force beyond compare, and what that meant for a republic that once had viewed large standing armies and constant warfare as anathemas to freedom.

In retrospect, the answer is all too straightforward: we need something to boast about, don’t we? In the once-upon-a-time “exceptional nation,” what else is there to praise to the skies or consider our pride and joy these days except our heroes? After all, this country can no longer boast of having anything like the world’s best educational outcomes, or healthcare system, or the most advanced and safest infrastructure, or the best democratic politics, so we better damn well be able to boast about having “the greatest fighting force” ever.

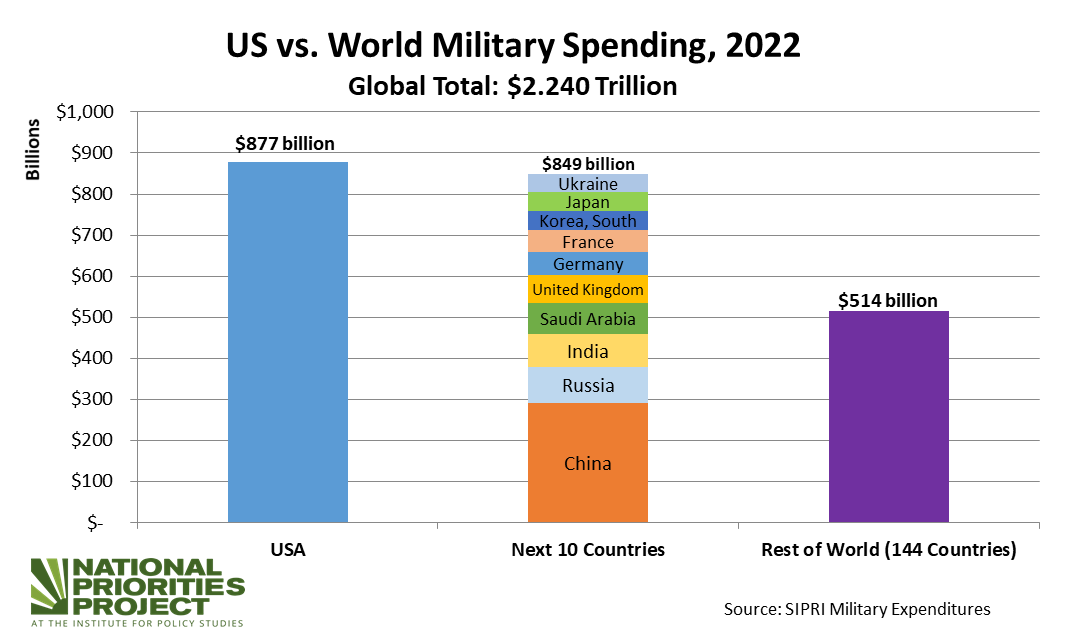

Leaving that boast aside, Americans could certainly brag about one thing this country has beyond compare: the most expensive military around and possibly ever. No country even comes close to our commitment of funds to wars, weapons (including nuclear ones at the Department of Energy), and global dominance. Indeed, the Pentagon’s budget for “defense” in 2023 exceeds that of the next 10 countries (mostly allies!) combined.

And from all of this, it seems to me, two questions arise: Are we truly getting what we pay so dearly for — the bestest, finest, most exceptional military ever? And even if we are, should a self-proclaimed democracy really want such a thing?

The answer to both those questions is, of course, no. After all, America hasn’t won a war in a convincing fashion since 1945. If this country keeps losing wars routinely and often enough catastrophically, as it has in places like Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq, how can we honestly say that we possess the world’s greatest fighting force? And if we nevertheless persist in such a boast, doesn’t that echo the rhetoric of militaristic empires of the past? (Remember when we used to think that only unhinged dictators like Adolf Hitler boasted of having peerless warriors in a megalomaniacal pursuit of global domination?)

Actually, I do believe the United States has the most exceptional military, just not in the way its boosters and cheerleaders like Austin, Bush, and Obama claimed. How is the U.S. military truly “exceptional”? Let me count the ways.

The Pentagon as a Budgetary Black Hole

In so many ways, the U.S. military is indeed exceptional. Let’s begin with its budget. At this very moment, Congress is debating a colossal “defense” budget of $886 billion for FY2024 (and all the debate is about issues that have little to do with the military). That defense spending bill, you may recall, was “only” $740 billion when President Joe Biden took office three years ago. In 2021, Biden withdrew U.S. forces from the disastrous war in Afghanistan, theoretically saving the taxpayer nearly $50 billion a year. Yet, in place of any sort of peace dividend, American taxpayers simply got an even higher bill as the Pentagon budget continued to soar.

Recall that, in his four years in office, Donald Trump increased military spending by 20%. Biden is now poised to achieve a similar 20% increase in just three years in office. And that increase largely doesn’t even include the cost of supporting Ukraine in its war with Russia — so far, somewhere between $120 billion and $200 billion and still rising.

Colossal budgets for weapons and war enjoy broad bipartisan support in Washington. It’s almost as if there were a military-industrial-congressional complex at work here! Where, in fact, did I ever hear a president warning us about that? Oh, perhaps I’m thinking of a certain farewell address by Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1961.

In all seriousness, there’s now a huge pentagonal-shaped black hole on the Potomac that’s devouring more than half of the federal discretionary budget annually. Even when Congress and the Pentagon allegedly try to enforce fiscal discipline, if not austerity elsewhere, the crushing gravitational pull of that hole just continues to suck in more money. Bet on that continuing as the Pentagon issues ever more warnings about a new cold war with China and Russia.

Given its money-sucking nature, perhaps you won’t be surprised to learn that the Pentagon is remarkably exceptional when it comes to failing fiscal audits — five of them in a row (the fifth failure being a “teachable moment,” according to its chief financial officer) — as its budget only continued to soar. Whether you’re talking about lost wars or failed audits, the Pentagon is eternally rewarded for its failures. Try running a “Mom and Pop” store on that basis and see how long you last.

Speaking of all those failed wars, perhaps you won’t be surprised to learn that they haven’t come cheaply. According to the Costs of War Project at Brown University, roughly 937,000 people have died since 9/11/2001 thanks to direct violence in this country’s “Global War on Terror” in Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, and elsewhere. (And the deaths of another 3.6 to 3.7 million people may be indirectly attributable to those same post-9/11 conflicts.) The financial cost to the American taxpayer has been roughly $8 trillion and rising even as the U.S. military continues its counterterror preparations and activities in 85 countries.

No other nation in the world sees its military as (to borrow from a short-lived Navy slogan) “a global force for good.” No other nation divides the whole world into military commands like AFRICOM for Africa and CENTCOM for the Middle East and parts of Central and South Asia, headed up by four-star generals and admirals. No other nation has a network of 750 foreign bases scattered across the globe. No other nation strives for full-spectrum dominance through “all-domain operations,” meaning not only the control of traditional “domains” of combat — the land, sea, and air — but also of space and cyberspace. While other countries are focused mainly on national defense (or regional aggressions of one sort or another), the U.S. military strives for total global and spatial dominance. Truly exceptional!

Strangely, in this never-ending, unbounded pursuit of dominance, results simply don’t matter. The Afghan War? Bungled, botched, and lost. The Iraq War? Built on lies and lost. Libya? We came, we saw, Libya’s leader (and so many innocents) died. Yet no one at the Pentagon was punished for any of those failures. In fact, to this day, it remains an accountability-free zone, exempt from meaningful oversight. If you’re a “modern major general,” why not pursue wars when you know you’ll never be punished for losing them?

Indeed, the few “exceptions” within the military-industrial-congressional complex who stood up for accountability, people of principle like Daniel Hale, Chelsea Manning, and Edward Snowden, were imprisoned or exiled. In fact, the U.S. government has even conspired to imprison a foreign publisher and transparency activist, Julian Assange, who published the truth about the American war on terror, by using a World War I-era espionage clause that only applies to American citizens.

And the record is even grimmer than that. In our post-9/11 years at war, as President Barack Obama admitted, “We tortured some folks” — and the only person punished for that was another whistleblower, John Kiriakou, who did his best to bring those war crimes to our attention.

And speaking of war crimes, isn’t it “exceptional” that the U.S. military plans to spend upwards of $2 trillion in the coming decades on a new generation of genocidal nuclear weapons? Those include new stealth bombers and new intercontinental ballistic missiles (ICBMs) for the Air Force, as well as new nuclear-missile-firing submarines for the Navy. Worse yet, the U.S. continues to reserve the right to use nuclear weapons first, presumably in the name of protecting life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. And of course, despite the countries — nine! — that now possess nukes, the U.S. remains the only one to have used them in wartime, in the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Finally, it turns out that the military is even immune from Supreme Court decisions! When SCOTUS recently overturned affirmative action for college admission, it carved out an exception for the military academies. Schools like West Point and Annapolis can still consider the race of their applicants, presumably to promote unit cohesionthrough proportional representation of minorities within the officer ranks, but our society at large apparently does not require racial equity for its cohesion.

A Most Exceptional Military Makes Its Wars and Their Ugliness Disappear

Here’s one of my favorite lines from the movie The Usual Suspects: “The greatest trick the devil ever pulled was convincing the world he did not exist.” The greatest trick the U.S. military ever pulled was essentially convincing us that its wars never existed. As Norman Solomon notes in his revealing book, War Made Invisible, the military-industrial-congressional complex has excelled at camouflaging the atrocious realitiesof war, rendering them almost entirely invisible to the American people. Call it the new American isolationism, only this time we’re isolated from the harrowing and horrific costs of war itself.

America is a nation perpetually at war, yet most of us live our lives with little or no perception of this. There is no longer a military draft. There are no war bond drives. You aren’t asked to make direct and personal sacrifices. You aren’t even asked to pay attention, let alone pay (except for those nearly trillion-dollar-a-year budgets and interest payments on a ballooning national debt, of course). You certainly aren’t asked for your permission for this country to fight its wars, as the Constitution demands. As President George W. Bush suggested after the 9/11 attacks, go visit Disneyworld! Enjoy life! Let America’s “best and brightest” handle the brutality, the degradation, and the ugliness of war, bright minds like former Vice President Dick (“So?”) Cheney and former Secretary of Defense Donald (“I don’t do quagmires”) Rumsfeld.

Did you hear something about the U.S. military being in Syria? In Somalia? Did you hear about the U.S. military supporting the Saudis in a brutal war of repression in Yemen? Did you notice how this country’s military interventions around the world kill, wound, and displace so many people of color, so much so that observers speak of the systemic racism of America’s wars? Is it truly progress that a more diverse military in terms of “color, creed, and background,” to use Secretary of Defense Austin’s words, has killed and is killing so many non-white peoples around the globe?

Praising the all-female-crewed flyover at the last Super Bowl or painting rainbow flags of inclusivity (or even blue and yellow flags for Ukraine) on cluster munitionswon’t soften the blows or quiet the screams. As one reader of my blog Bracing Viewsso aptly put it: “The diversity the war parties [Democrats and Republicans] will not tolerate is diversity of thought.”

Of course, the U.S. military isn’t solely to blame here. Senior officers will claim their duty is not to make policy at all but to salute smartly as the president and Congress order them about. The reality, however, is different. The military is, in fact, at the core of America’s shadow government with enormous influence over policymaking. It’s not merely an instrument of power; it is power — and exceptionally powerful at that. And that form of power simply isn’t conducive to liberty and freedom, whether inside America’s borders or beyond them.

Wait! What am I saying? Stop thinking about all that! America is, after all, the exceptional nation and its military, a band of freedom fighters. In Iraq, where war and sanctions killed untold numbers of Iraqi children in the 1990s, the sacrifice was “worth it,” as former Secretary of State Madeleine Albright once reassured Americans on 60 Minutes.

Even when government actions kill children, lots of children, it’s for the greater good. If this troubles you, go to Disney and take your kids with you. You don’t like Disney? Then, hark back to that old marching song of World War I and “pack up your troubles in your old kit-bag, and smile, smile, smile.” Remember, America’s troops are freedom-delivering heroes and your job is to smile and support them without question.

Have I made my point? I hope so. And yes, the U.S. military is indeed exceptional and being so, being #1 (or claiming you are anyway) means never having to say you’re sorry, no matter how many innocents you kill or maim, how many lives you disrupt and destroy, how many lies you tell.

I must admit, though, that, despite the endless celebration of our military’s exceptionalism and “greatness,” a fragment of scripture from my Catholic upbringing haunts me still: Pride goeth before destruction and a haughty spirit before a fall.

Copyright 2023 William J. Astore