W.J. Astore

In my latest article for TomDispatch.com, I suggest how America can pursue a wiser, more peaceful, course. This is exactly what our leaders are not doing (and haven’t been doing for decades), as I document in the first half of my article, which I’m sharing here. Bottom line: perpetual war doesn’t produce perpetual peace. Nor does it make us safer.

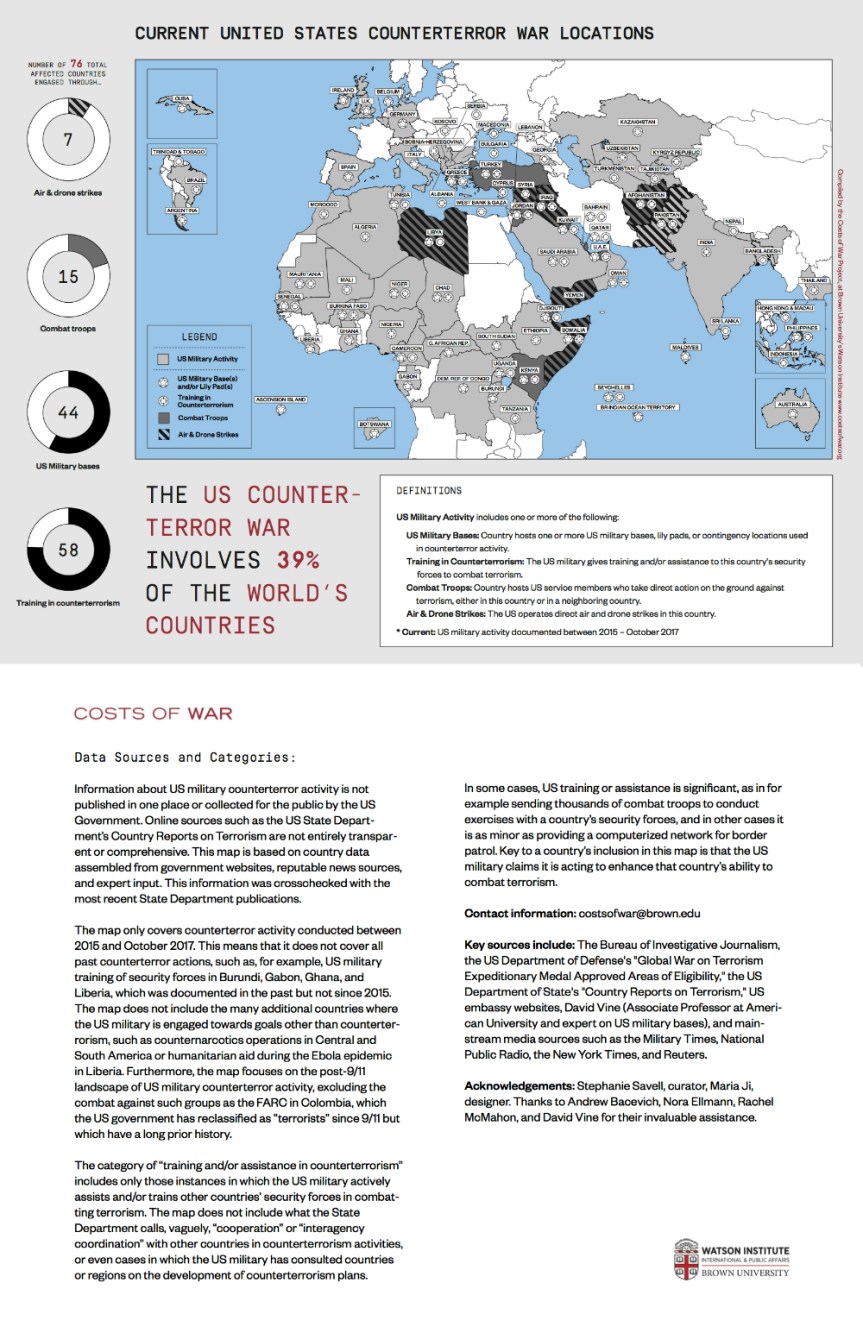

Whether the rationale is the need to wage a war on terror involving 76 countries or renewed preparations for a struggle against peer competitors Russia and China (as Defense Secretary James Mattis suggested recently while introducing America’s new National Defense Strategy), the U.S. military is engaged globally. A network of 800 military bases spread across 172 countries helps enable its wars and interventions. By the count of the Pentagon, at the end of the last fiscal year about 291,000 personnel (including reserves and Department of Defense civilians) were deployed in 183 countries worldwide, which is the functional definition of a military uncontained. Lady Liberty may temporarily close when the U.S. government grinds to a halt, but the country’s foreign military commitments, especially its wars, just keep humming along.

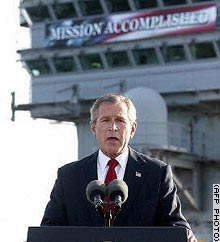

As a student of history, I was warned to avoid the notion of inevitability. Still, given such data points and others like them, is there anything more predictable in this country’s future than incessant warfare without a true victory in sight? Indeed, the last clear-cut American victory, the last true “mission accomplished” moment in a war of any significance, came in 1945 with the end of World War II.

Yet the lack of clear victories since then seems to faze no one in Washington. In this century, presidents have regularly boasted that the U.S. military is the finest fighting force in human history, while no less regularly demanding that the most powerful military in today’s world be “rebuilt” and funded at ever more staggering levels. Indeed, while on the campaign trail, Donald Trump promised he’d invest so much in the military that it would become “so big and so strong and so great, and it will be so powerful that I don’t think we’re ever going to have to use it.”

As soon as he took office, however, he promptly appointed a set of generals to key positions in his government, stored the mothballs, and went back to war. Here, then, is a brief rundown of the first year of his presidency in war terms.

In 2017, Afghanistan saw a mini-surge of roughly 4,000 additional U.S. troops (with more to come), a major spike in air strikes, and an onslaught of munitions of all sorts, including MOAB (the mother of all bombs), the never-before-used largest non-nuclear bomb in the U.S. arsenal, as well as precision weapons fired by B-52s against suspected Taliban drug laboratories. By the Air Force’s own count, 4,361 weapons were “released” in Afghanistan in 2017 compared to 1,337 in 2016. Despite this commitment of warriors and weapons, the Afghan war remains — according to American commanders putting the best possible light on the situation — “stalemated,” with that country’s capital Kabul currently under siege.

How about Operation Inherent Resolve against the Islamic State? U.S.-led coalition forces have launched more than 10,000 airstrikes in Iraq and Syria since Donald Trump became president, unleashing 39,577 weapons in 2017. (The figure for 2016 was 30,743.) The “caliphate” is now gone and ISIS deflated but not defeated, since you can’t extinguish an ideology solely with bombs. Meanwhile, along the Syrian-Turkish border a new conflict seems to be heating up between American-backed Kurdish forces and NATO ally Turkey.

Yet another strife-riven country, Yemen, witnessed a sixfold increase in U.S. airstrikes against al-Qaeda on the Arabian Peninsula (from 21 in 2016 to more than 131 in 2017). In Somalia, which has also seen a rise in such strikes against al-Shabaab militants, U.S. forces on the ground have reached numbers not seen since the Black Hawk Down incident of 1993. In each of these countries, there are yet more ruins, yet more civilian casualties, and yet more displaced people.

Finally, we come to North Korea. Though no real shots have yet been fired, rhetorical shots by two less-than-stable leaders, “Little Rocket Man” Kim Jong-un and “dotard” Donald Trump, raise the possibility of a regional bloodbath. Trump, seemingly favoring military solutions to North Korea’s nuclear program even as his administration touts a new generation of more usable nuclear warheads, has been remarkably successful in moving the world’s doomsday clock ever closer to midnight.

Clearly, his “great” and “powerful” military has hardly been standing idly on the sidelines looking “big” and “strong.” More than ever, in fact, it seems to be lashing out across the Greater Middle East and Africa. Seventeen years after the 9/11 attacks began the Global War on Terror, all of this represents an eerily familiar attempt by the U.S. military to kill its way to victory, whether against the Taliban, ISIS, or other terrorist organizations.

This kinetic reality should surprise no one. Once you invest so much in your military — not just financially but also culturally (by continually celebrating it in a fashion which has come to seem like a quasi-faith) — it’s natural to want to put it to use. This has been true of all recent administrations, Democratic and Republican alike, as reflected in the infamous question Madeleine Albright posed to Chairman of the Joint Chiefs Colin Powell in 1992: “What’s the point of having this superb military you’re always talking about if we can’t use it?”

With the very word “peace” rarely in Washington’s political vocabulary, America’s never-ending version of war seems as inevitable as anything is likely to be in history. Significant contingents of U.S. troops and contractors remain an enduring presence in Iraq and there are now 2,000 U.S. Special Operations forces and other personnel in Syria for the long haul. They are ostensibly engaged in training and stability operations. In Washington, however, the urge for regime change in both Syria and Iran remains strong — in the case of Iran implacably so. If past is prologue, then considering previous regime-change operations in Afghanistan, Iraq, and Libya, the future looks grim indeed.

Despite the dismal record of the last decade and a half, our civilian leaders continue to insist that this country must have a military not only second to none but globally dominant. And few here wonder what such a quest for total dominance, the desire for absolute power, could do to this country. Two centuries ago, however, writing to Thomas Jefferson, John Adams couldn’t have been clearer on the subject. Power, he said, “must never be trusted without a check.”

Despite the dismal record of the last decade and a half, our civilian leaders continue to insist that this country must have a military not only second to none but globally dominant. And few here wonder what such a quest for total dominance, the desire for absolute power, could do to this country. Two centuries ago, however, writing to Thomas Jefferson, John Adams couldn’t have been clearer on the subject. Power, he said, “must never be trusted without a check.”

The question today for the American people: How is the dominant military power of which U.S. leaders so casually boast to be checked? How is the country’s almost total reliance on the military in foreign affairs to be reined in? How can the plans of the profiteers and arms makers to keep the good times rolling be brought under control?

As a start, consider one of Donald Trump’s favorite generals, Douglas MacArthur, speaking to the Sperry Rand Corporation in 1957:

“Our swollen budgets constantly have been misrepresented to the public. Our government has kept us in a perpetual state of fear — kept us in a continuous stampede of patriotic fervor — with the cry of grave national emergency. Always there has been some terrible evil at home or some monstrous foreign power that was going to gobble us up if we did not blindly rally behind it by furnishing the exorbitant funds demanded. Yet, in retrospect, these disasters seem never to have happened, seem never to have been quite real.”

No peacenik MacArthur. Other famed generals like Smedley Butler and Dwight D. Eisenhower spoke out with far more vigor against the corruptions of war and the perils to a democracy of an ever more powerful military, though such sentiments are seldom heard in this country today. Instead, America’s leaders insist that other people judge us by our words, our stated good intentions, not our murderous deeds and their results.

For ten suggestions (plus a bonus) on how the U.S. can pursue a wiser, and far less bellicose, course, please read the rest of my article here at TomDispatch.com.