W.J. Astore

Most Americans would say we have a military for national defense and security. But our military is not a defensive force. Defense is not its ethos, nor is it how our military is structured. Our military is a power-projection force. It is an offensive force. It is designed to take the fight to the enemy. To strike first, usually justified as “preemptive” or “preventive” action. It’s a military that believes “the best defense is a good offense,” with leaders who believe in “full-spectrum dominance,” i.e. quick and overwhelming victories, enabled by superior technology and firepower, whether on the ground, on the seas, in the air, or even in space or cyberspace.

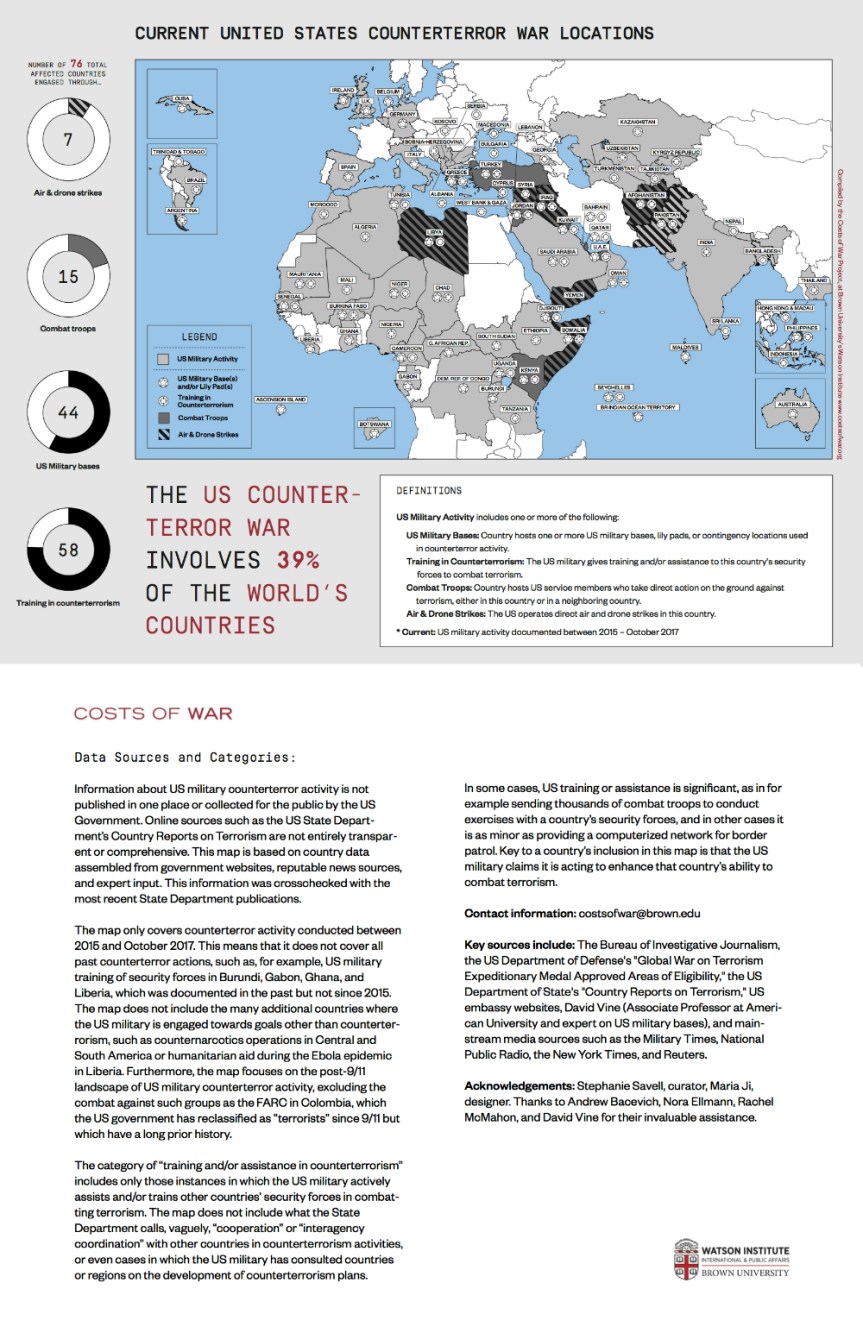

Thus the “global war on terror” wasn’t a misnomer, or at least the word “global” wasn’t. Consider the article below today at TomDispatch.com by Stephanie Savell. Our military is involved in at least 80 countries in this global war, with no downsizing of the mission evident in the immediate future (perhaps, perhaps, a slow withdrawal from Syria; perhaps, perhaps, a winding down of the Afghan War; meanwhile, we hear rumblings of possible military interventions in Venezuela and Iran).

Here’s a sad reality: U.S. military troops and military contractors/weapons dealers have become America’s chief missionaries, our ambassadors, our diplomats, our aid workers, even our “peace” corps, if by “peace” you mean more weaponry and combat training in the name of greater “stability.”

We’ve become a one-dimensional country. All military all the time. W.J. Astore

Mapping the American War on Terror

Now in 80 Countries, It Couldn’t Be More Global

By Stephanie Savell

In September 2001, the Bush administration launched the “Global War on Terror.” Though “global” has long since been dropped from the name, as it turns out, they weren’t kidding.

When I first set out to map all the places in the world where the United States is still fighting terrorism so many years later, I didn’t think it would be that hard to do. This was before the 2017 incident in Niger in which four American soldiers were killed on a counterterror mission and Americans were given an inkling of how far-reaching the war on terrorism might really be. I imagined a map that would highlight Afghanistan, Iraq, Pakistan, and Syria — the places many Americans automatically think of in association with the war on terror — as well as perhaps a dozen less-noticed countries like the Philippines and Somalia. I had no idea that I was embarking on a research odyssey that would, in its second annual update, map U.S. counterterror missions in 80 countries in 2017 and 2018, or 40% of the nations on this planet (a map first featured in Smithsonian magazine).

As co-director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, I’m all too aware of the costs that accompany such a sprawling overseas presence. Our project’s research shows that, since 2001, the U.S. war on terror has resulted in the loss — conservatively estimated — of almost half a million lives in Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan alone. By the end of 2019, we also estimate that Washington’s global war will cost American taxpayers no less than $5.9 trillion already spent and in commitments to caring for veterans of the war throughout their lifetimes.

In general, the American public has largely ignored these post-9/11 wars and their costs. But the vastness of Washington’s counterterror activities suggests, now more than ever, that it’s time to pay attention. Recently, the Trump administration has been talking of withdrawing from Syria and negotiating peace with the Taliban in Afghanistan. Yet, unbeknownst to many Americans, the war on terror reaches far beyond such lands and under Trump is actually ramping up in a number of places. That our counterterror missions are so extensive and their costs so staggeringly high should prompt Americans to demand answers to a few obvious and urgent questions: Is this global war truly making Americans safer? Is it reducing violence against civilians in the U.S. and other places? If, as I believe, the answer to both those questions is no, then isn’t there a more effective way to accomplish such goals?

Combat or “Training” and “Assisting”?

The major obstacle to creating our database, my research team would discover, was that the U.S. government is often so secretive about its war on terror. The Constitution gives Congress the right and responsibility to declare war, offering the citizens of this country, at least in theory, some means of input. And yet, in the name of operational security, the military classifies most information about its counterterror activities abroad.

This is particularly true of missions in which there are American boots on the ground engaging in direct action against militants, a reality, my team and I found, in 14 different countries in the last two years. The list includes Afghanistan and Syria, of course, but also some lesser known and unexpected places like Libya, Tunisia, Somalia, Mali, and Kenya. Officially, many of these are labeled “train, advise, and assist” missions, in which the U.S. military ostensibly works to support local militaries fighting groups that Washington labels terrorist organizations. Unofficially, the line between “assistance” and combat turns out to be, at best, blurry.

Some outstanding investigative journalists have documented the way this shadow war has been playing out, predominantly in Africa. In Niger in October 2017, as journalists subsequently revealed, what was officially a training mission proved to be a “kill or capture” operation directed at a suspected terrorist.

Some outstanding investigative journalists have documented the way this shadow war has been playing out, predominantly in Africa. In Niger in October 2017, as journalists subsequently revealed, what was officially a training mission proved to be a “kill or capture” operation directed at a suspected terrorist.

Such missions occur regularly. In Kenya, for instance, American service members are actively hunting the militants of al-Shabaab, a US-designated terrorist group. In Tunisia, there was at least one outright battle between joint U.S.-Tunisian forces and al-Qaeda militants. Indeed, two U.S. service members were later awarded medals of valor for their actions there, a clue that led journalists to discover that there had been a battle in the first place.

In yet other African countries, U.S. Special Operations forces have planned and controlled missions, operating in “cooperation with” — but actually in charge of — their African counterparts. In creating our database, we erred on the side of caution, only documenting combat in countries where we had at least two credible sources of proof, and checking in with experts and journalists who could provide us with additional information. In other words, American troops have undoubtedly been engaged in combat in even more places than we’ve been able to document.

Another striking finding in our research was just how many countries there were — 65 in all — in which the U.S. “trains” and/or “assists” local security forces in counterterrorism. While the military does much of this training, the State Department is also surprisingly heavily involved, funding and training police, military, and border patrol agents in many countries. It also donates equipment, including vehicle X-ray detection machines and contraband inspection kits. In addition, it develops programs it labels “Countering Violent Extremism,” which represent a soft-power approach, focusing on public education and other tools to “counter terrorist safe havens and recruitment.”

Such training and assistance occurs across the Middle East and Africa, as well as in some places in Asia and Latin America. American “law enforcement entities” trained security forces in Brazil to monitor terrorist threats in advance of the 2016 Summer Olympics, for example (and continued the partnership in 2017). Similarly, U.S. border patrol agents worked with their counterparts in Argentina to crack down on suspected money laundering by terrorist groups in the illicit marketplaces of the tri-border region that lies between Argentina, Brazil, and Paraguay.

To many Americans, all of this may sound relatively innocuous — like little more than generous, neighborly help with policing or a sensibly self-interested fighting-them-over-there-before-they-get-here set of policies. But shouldn’t we know better after all these years of hearing such claims in places like Iraq and Afghanistan where the results were anything but harmless or effective?

Such training has often fed into, or been used for, the grimmest of purposes in the many countries involved. In Nigeria, for instance, the U.S. military continues to work closely with local security forces which have used torture and committed extrajudicial killings, as well as engaging in sexual exploitation and abuse. In the Philippines, it has conducted large-scale joint military exercises in cooperation with President Rodrigo Duterte’s military, even as the police at his command continue to inflict horrific violence on that country’s citizenry.

The government of Djibouti, which for years has hosted the largest U.S. military base in Africa, Camp Lemonnier, also uses its anti-terrorism laws to prosecute internal dissidents. The State Department has not attempted to hide the way its own training programs have fed into a larger kind of repression in that country (and others). According to its 2017 Country Reports on Terrorism, a document that annually provides Congress with an overview of terrorism and anti-terror cooperation with the United States in a designated set of countries, in Djibouti, “the government continued to use counterterrorism legislation to suppress criticism by detaining and prosecuting opposition figures and other activists.”

In that country and many other allied nations, Washington’s terror-training programs feed into or reinforce human-rights abuses by local forces as authoritarian governments adopt “anti-terrorism” as the latest excuse for repressive practices of all sorts.

A Vast Military Footprint

As we were trying to document those 65 training-and-assistance locations of the U.S. military, the State Department reports proved an important source of information, even if they were often ambiguous about what was really going on. They regularly relied on loose terms like “security forces,” while failing to directly address the role played by our military in each of those countries.

Sometimes, as I read them and tried to figure out what was happening in distant lands, I had a nagging feeling that what the American military was doing, rather than coming into focus, was eternally receding from view. In the end, we felt certain in identifying those 14 countries in which American military personnel have seen combat in the war on terror in 2017-2018. We also found it relatively easy to document the seven countries in which, in the last two years, the U.S. has launched drone or other air strikes against what the government labels terrorist targets (but which regularly kill civilians as well): Afghanistan, Iraq, Libya, Pakistan, Somalia, Syria, and Yemen. These were the highest-intensity elements of that U.S. global war. However, this still represented a relatively small portion of the 80 countries we ended up including on our map.

In part, that was because I realized that the U.S. military tends to advertise — or at least not hide — many of the military exercises it directs or takes part in abroad. After all, these are intended to display the country’s global military might, deter enemies (in this case, terrorists), and bolster alliances with strategically chosen allies. Such exercises, which we documented as being explicitly focused on counterterrorism in 26 countries, along with lands which host American bases or smaller military outposts also involved in anti-terrorist activities, provide a sense of the armed forces’ behemoth footprint in the war on terror.

Although there are more than 800 American military bases around the world, we included in our map only those 40 countries in which such bases are directly involved in the counterterror war, including Germany and other European nations that are important staging areas for American operations in the Middle East and Africa.

To sum up: our completed map indicates that, in 2017 and 2018, seven countries were targeted by U.S. air strikes; double that number were sites where American military personnel engaged directly in ground combat; 26 countries were locations for joint military exercises; 40 hosted bases involved in the war on terror; and in 65, local military and security forces received counterterrorism-oriented “training and assistance.”

A Better Grand Plan

How often in the last 17 years has Congress or the American public debated the expansion of the war on terror to such a staggering range of places? The answer is: seldom indeed.

After so many years of silence and inactivity here at home, recent media and congressional attention to American wars in Afghanistan, Syria, and Yemen represents a new trend. Members of Congress have finally begun calling for discussion of parts of the war on terror. Last Wednesday, for instance, the House of Representatives voted to end U.S. support for the Saudi-led war in Yemen, and the Senate has passed legislation requiring Congress to vote on the same issue sometime in the coming months.

On February 6th, the House Armed Services Committee finally held a hearing on the Pentagon’s “counterterrorism approach” — a subject Congress as a whole has not debated since, several days after the 9/11 attacks, it passed the Authorization for the Use of Military Force that Presidents George W. Bush, Barack Obama, and now Donald Trump have all used to wage the ongoing global war. Congress has not debated or voted on the sprawling expansion of that effort in all the years since. And judging from the befuddled reactions of several members of Congress to the deaths of those four soldiers in Niger in 2017, most of them were (and many probably still are) largely ignorant of how far the global war they’ve seldom bothered to discuss now reaches.

With potential shifts afoot in Trump administration policy on Syria and Afghanistan, isn’t it finally time to assess in the broadest possible way the necessity and efficacy of extending the war on terror to so many different places? Research has shown that using war to address terror tactics is a fruitless approach. Quite the opposite of achieving this country’s goals, from Libya to Syria, Niger to Afghanistan, the U.S. military presence abroad has often only fueled intense resentment of America. It has helped to both spread terror movements and provide yet more recruits to extremist Islamist groups, which have multiplied substantially since 9/11.

In the name of the war on terror in countries like Somalia, diplomatic activities, aid, and support for human rights have dwindled in favor of an ever more militarized American stance. Yet research shows that, in the long term, it is far more effective and sustainable to address the underlying grievances that fuel terrorist violence than to answer them on the battlefield.

All told, it should be clear that another kind of grand plan is needed to deal with the threat of terrorism both globally and to Americans — one that relies on a far smaller U.S. military footprint and costs far less blood and treasure. It’s also high time to put this threat in context and acknowledge that other developments, like climate change, may pose a far greater danger to our country.

Stephanie Savell, a TomDispatch regular, is co-director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University’s Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs. An anthropologist, she conducts research on security and activism in the U.S. and in Brazil. She co-authored The Civic Imagination: Making a Difference in American Political Life.

Copyright 2019 Stephanie Savell