W.J. Astore

Our government likes to talk about global security, which in their minds is basically synonymous with homeland security. They argue that the best defense is a good offense, that “leaning forward in the foxhole,” or always being ready to attack, is the best way to keep Americans safe. Hence the 800 U.S. military bases in foreign countries, the deployment of special operations units to 130+ countries, and the never-ending “war on terror.”

Consider this snippet from today’s FP: Foreign Policy report:

If Congress votes through the massive tax cuts currently on the House floor, it would likely mean future cuts to Pentagon budgets “for training, maintenance, force structure, flight missions, procurement and other key programs.”

That’s according to former defense secretaries Leon E. Panetta, Chuck Hagel and Ash Carter, who sent a letter to congressional leadership Wednesday opposing the plan. “The result is the growing danger of a ‘hollowed out’ military force that lacks the ability to sustain the intensive deployment requirements of our global defense mission,” the secretaries wrote.

“Our global defense mission”: this vision that the U.S., in order to be secure, must dominate the world ensures profligate “defense” spending, to the tune of nearly $700 billion for 2018. Indeed, the Congress and the President are currently competing to see which branch of government can throw more money at the Pentagon, all in the name of “security,” naturally.

Here’s a quick summary of the new “defense” bill and what it authorizes (from the Washington Post):

The bill as it stands increases financial support for missile defense, larger troop salaries and modernizing, expanding and improving the military’s fleet of ships and warplanes. The legislation dedicates billions more than Trump’s request for key pieces of military equipment, such as Joint Strike Fighters — there are 20 more in the bill than in the president’s request — and increasing the size of the armed forces. The bill also outlines an increase of almost 20,000 service members — nearly twice Trump’s request.

In the House of Representatives, the bill passed by a vote of 356-70. At least Congress can agree on something — more and more money for the Pentagon. (The $700 billion price tag includes $65.7 billion “for combat operations in Iraq, Afghanistan, Syria, Yemen, various places in Africa, and elsewhere,” notes FP: Foreign Policy.)

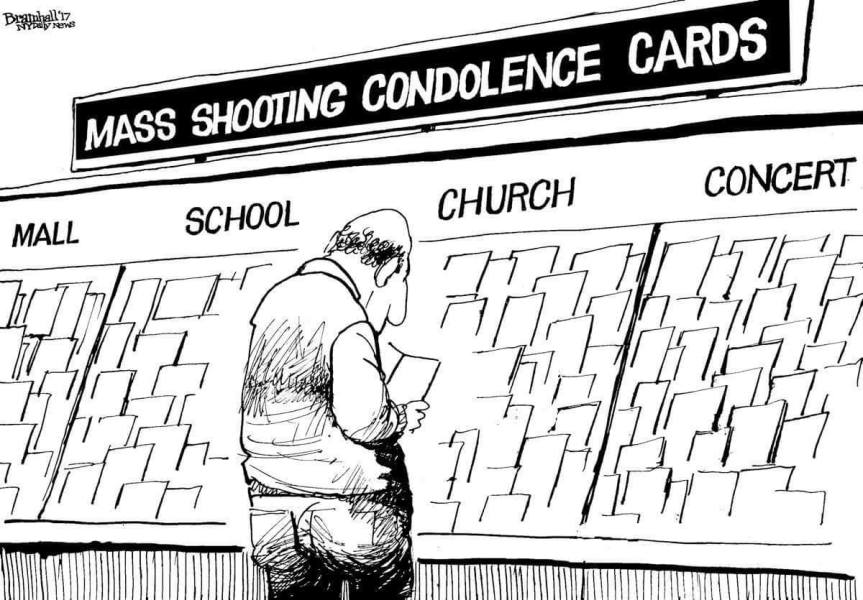

Besides all this wasteful spending (the Pentagon has yet to pass an audit!), the vision itself is deeply flawed. If you want to defend America, defend it. Strengthen the National Guard. Increase security at the border (including cyber security). Spend money on the Coast Guard. And, more than anything, start closing military bases overseas. End U.S. participation in wars in Afghanistan, Iraq, and throughout the greater Middle East and Africa. Bring ground troops home. And end air and drone attacks (this would also end the Air Force’s “crisis” of being short nearly 2000 pilots).

This is not a plea for isolationism. It’s a quest for sanity. America is not made safer by spreading military forces around the globe while bombing every “terrorist” in sight. Quite the reverse.

Until we change our vision of what national defense really means–and what it requires–America will be less safe, less secure, and less democratic.