W.J. Astore

Winning a war based on lies is truly a fool’s errand, which is why the U.S. military’s record since World War II is so poor. Yet no one is ever held responsible for these lies, which suggests something worse than a losing military: one that is without honor, especially among the brass. That’s the theme of my latest article for TomDispatch, which is appended below in its entirety.

As a military professor for six years at the U.S. Air Force Academy in the 1990s, I often walked past the honor code prominently displayed for all cadets to see. Its message was simple and clear: they were not to tolerate lying, cheating, stealing, or similar dishonorable acts. Yet that’s exactly what the U.S. military and many of America’s senior civilian leaders have been doing from the Vietnam War era to this very day: lying and cooking the books, while cheating and stealing from the American people. And yet the most remarkable thing may be that no honor code turns out to apply to them, so they’ve suffered no consequences for their mendacity and malfeasance.

Where’s the “honor” in that?

It may surprise you to learn that “integrity first” is the primary core value of my former service, the U.S. Air Force. Considering the revelations of the Pentagon Papers, leaked by Daniel Ellsberg in 1971; the Afghan War papers, first revealed by the Washington Post in 2019; and the lack of weapons of mass destruction in Iraq, among other evidence of the lying and deception that led to the invasion and occupation of that country, you’ll excuse me for assuming that, for decades now when it comes to war, “integrity optional” has been the true core value of our senior military leaders and top government officials.

As a retired Air Force officer, let me tell you this: honor code or not, you can’t win a war with lies — America proved that in Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq — nor can you build an honorable military with them. How could our high command not have reached such a conclusion themselves after all this time?

So Many Defeats, So Little Honesty

Like many other institutions, the U.S. military carries with it the seeds of its own destruction. After all, despite being funded in a fashion beyond compare and spreading its peculiar brand of destruction around the globe, its system of war hasn’t triumphed in a significant conflict since World War II (with the war in Korea remaining, almost three-quarters of a century later, in a painful and festering stalemate). Even the ending of the Cold War, allegedly won when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, only led to further wanton military adventurism and, finally, defeat at an unsustainable cost — more than $8 trillion — in Washington’s ill-fated Global War on Terror. And yet, years later, that military still has a stranglehold on the national budget.

So many defeats, so little honesty: that’s the catchphrase I’d use to characterize this country’s military record since 1945. Keeping the money flowing and the wars going proved far more important than integrity or, certainly, the truth. Yet when you sacrifice integrity and the truth in the cause of concealing defeat, you lose much more than a war or two. You lose honor — in the long run, an unsustainable price for any military to pay.

Or rather it should be unsustainable, yet the American people have continued to “support” their military, both by funding it astronomically and expressing seemingly eternal confidence in it — though, after all these years, trust in the military has dipped somewhat recently. Still, in all this time, no one in the senior ranks, civilian or military, has ever truly been called to account for losing wars prolonged by self-serving lies. In fact, too many of our losing generals have gone right through that infamous “revolving door” into the industrial part of the military-industrial complex — only to sometimes return to take top government positions.

Our military has, in fact, developed a narrative that’s proven remarkably effective in insulating it from accountability. It goes something like this: U.S. troops fought hard in [put the name of the country here], so don’t blame us. Indeed, you must support us, especially given all the casualties of our wars. They and the generals did their best, under the usual political constraints. On occasion, mistakes were made, but the military and the government had good and honorable intentions in Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, and elsewhere.

Besides, were you there, Charlie? If you weren’t, then STFU, as the acronym goes, and be grateful for the security you take for granted, earned by America’s heroes while you were sitting on your fat ass safe at home.

It’s a narrative I’ve heard time and time again and it’s proven persuasive, partially because it requires the rest of us, in a conscription-free country, to do nothing and think nothing about that. Ignorance is strength, after all.

War Is Brutal

The reality of it all, however, is so much harsher than that. Senior military leaders have performed poorly. War crimes have been covered up. Wars fought in the name of helping others have produced horrendous civilian casualties and stunning numbers of refugees. Even as those wars were being lost, what President Dwight D. Eisenhowerfirst labeled the military-industrial complex has enjoyed windfall profits and expanding power. Again, there’s been no accountability for failure. In fact, only whistleblowing truth-tellers like Chelsea Manning and Daniel Hale have been punished and jailed.

Ready for an even harsher reality? America is a nation being unmade by war, the very opposite of what most Americans are taught. Allow me to explain. As a country, we typically celebrate the lofty ideals and brave citizen-soldiers of the American Revolution. We similarly celebrate the Second American Revolution, otherwise known as the Civil War, for the elimination of slavery and reunification of the country; after which, we celebrate World War II, including the rise of the Greatest Generation, America as the arsenal of democracy, and our emergence as the global superpower.

By celebrating those three wars and essentially ignoring much of the rest of our history, we tend to view war itself as a positive and creative act. We see it as making America, as part of our unique exceptionalism. Not surprisingly, then, militarism in this country is impossible to imagine. We tend to see ourselves, in fact, as uniquely immune to it, even as war and military expenditures have come to dominate our foreign policy, bleeding into domestic policy as well.

If we as Americans continue to imagine war as a creative, positive, essential part of who we are, we’ll also continue to pursue it. Or rather, if we continue to lie to ourselves about war, it will persist.

It’s time for us to begin seeing it not as our making but our unmaking, potentially even our breaking — as democracy’s undoing as well as the brutal thing it truly is.

A retired U.S. military officer, educated by the system, I freely admit to having shared some of its flaws. When I was an Air Force engineer, for instance, I focused more on analysis and quantification than on synthesis and qualification. Reducing everything to numbers, I realize now, helps provide an illusion of clarity, even mastery. It becomes another form of lying, encouraging us to meddle in things we don’t understand.

This was certainly true of Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, his “whiz kids,” and General William Westmoreland during the Vietnam War; nor had much changed when it came to Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld and General David Petraeus, among others, in the Afghan and Iraq War years. In both eras, our military leaders wielded metrics and swore they were winning even as those wars circled the drain.

And worse yet, they were never held accountable for those disasters or the blunders and lies that went with them (though the antiwar movement of the Vietnam era certainly tried). All these years later, with the Pentagon still ascendant in Washington, it should be obvious that something has truly gone rotten in our system.

Here’s the rub: as the military and one administration after another lied to the American people about those wars, they also lied to themselves, even though such conflicts produced plenty of internal “papers” that raised serious concerns about lack of progress. Robert McNamara typically knew that the situation in Vietnam was dire and the war essentially unwinnable. Yet he continued to issue rosy public reports of progress, while calling for more troops to pursue that illusive “light at the end of the tunnel.” Similarly, the Afghan War papers released by the Washington Post show that senior military and civilian leaders realized that war, too, was going poorly almost from the beginning, yet they reported the very opposite to the American people. So many corners were being “turned,” so much “progress” being made in official reports even as the military was building its own rhetorical coffin in that Afghan graveyard of empires.

Too bad wars aren’t won by “spin.” If they were, the U.S. military would be undefeated.

Two Books to Help Us See the Lies

Two recent books help us see that spin for what it was. In Because Our Fathers Lied, Craig McNamara, Robert’s son, reflects on his father’s dishonesty about the Vietnam War and the reasons for it. Loyalty was perhaps the lead one, he writes. McNamara suppressed his own serious misgivings out of misplaced loyalty to two presidents, John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson, while simultaneously preserving his own position of power in the government.

Robert McNamara would, in fact, later pen his own mea culpa, admitting how “terribly wrong” he’d been in urging the prosecution of that war. Yet Craig finds his father’s late confession of regret significantly less than forthright and fully honest. Robert McNamara fell back on historical ignorance about Vietnam as the key contributing factor in his unwise decision-making, but his son is blunt in accusing his dad of unalloyed dishonesty. Hence the title of his book, citing Rudyard Kipling’s pained confession of his own complicity in sending his son to die in the trenches of World War I: “If any question why we died/Tell them, because our fathers lied.”

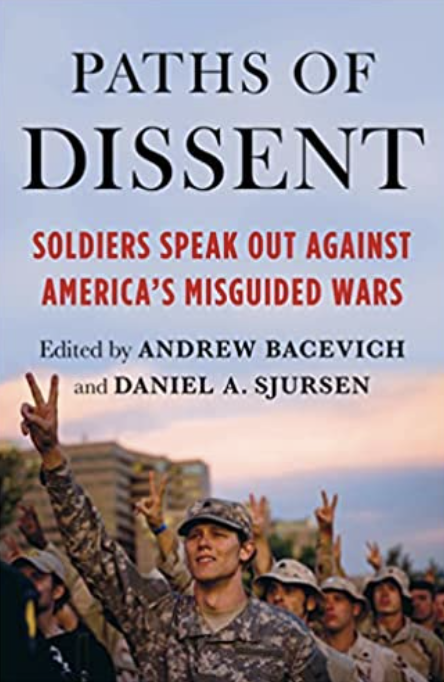

The second book is Paths of Dissent: Soldiers Speak Out Against America’s Misguided Wars, edited by Andrew Bacevich and Danny Sjursen. In my view, the word “misguided” doesn’t quite capture the book’s powerful essence, since it gathers 15 remarkable essays by Americans who served in Afghanistan and Iraq and witnessed the patent dishonesty and folly of those wars. None dare speak of failure might be a subtheme of these essays, as initially highly motivated and well-trained troops became disillusioned by wars that went nowhere, even as their comrades often paid the ultimate price, being horribly wounded or dying in those conflicts driven by lies.

This is more than a work of dissent by disillusioned troops, however. It’s a call for the rest of us to act. Dissent, as West Point graduate and Army Captain Erik Edstrom reminds us, “is nothing short of a moral obligation” when immoral wars are driven by systemic dishonesty. Army Lieutenant Colonel Daniel Davis, who blew an early whistle on how poorly the Afghan War was going, writes of his “seething” anger “at the absurdity and unconcern for the lives of my fellow soldiers displayed by so many” of the Army’s senior leaders.

Former Marine Matthew Hoh, who resigned from the State Department in opposition to the Afghan “surge” ordered by President Barack Obama, speaks movingly of his own “guilt, regret, and shame” at having served in Afghanistan as a troop commander and wonders whether he can ever atone for it. Like Craig McNamara, Hoh warns of the dangers of misplaced loyalty. He remembers telling himself that he was best suited to lead his fellow Marines in war, no matter how misbegotten and dishonorable that conflict was. Yet he confesses that falling back on duty and being loyal to “his” Marines, while suppressing the infamies of the war itself, became “a washing of the hands, a self-absolution that ignores one’s complicity” in furthering a brutal conflict fed by lies.

As I read those essays, I came to see anew how this country’s senior leaders, military and civilian, consistently underestimated the brutalizing impact of war, which, in turn, leads me to the ultimate lie of war: that it is somehow good, or at least necessary — making all the lying (and killing) worth it, whether in the name of a victory to come or of duty, honor, and country. Yet there is no honor in lying, in keeping the truth hidden from the American people. Indeed, there is something distinctly dishonorable about waging wars kept viable only by lies, obfuscation, and propaganda.

An Epigram from Goethe

John Keegan, the esteemed military historian, cites an epigram from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe as being essential to thinking about militaries and their wars. “Goods gone, something gone; honor gone, much gone; courage gone, all gone.”

The U.S. military has no shortage of goods, given its whopping expenditures on weaponry and equipment of all sorts; among the troops, it doesn’t lack for courage or fighting spirit, not yet, anyway. But it does lack honor, especially at the top. Much is gone when a military ceases to tell the truth to itself and especially to the people from whom its forces are drawn. And courage is wasted when in the service of lies.

Courage wasted: Is there a worst fate for a military establishment that prides itself on its members being all volunteers and is now having trouble filling its ranks?

Copyright 2022 William J. Astore