W.J. Astore

There was a time when American democracy, however imperfectly practiced, and American ideals served to inspire peoples and independence movements around the world. Heck, even Ho Chi Minh in the 1940s confessed his admiration for Thomas Jefferson and the U.S. Declaration of Independence. But now it seems all that really matters in our foreign policy is troops and weapons. If we’re not basing troops or at least deploying them to a country, or if we’re not exporting arms to a country, we believe we have no influence.

So: Unless we’re fighting wars in Iraq (or Syria, or maybe even Iran?), the United States has no leverage. Indeed, in Iraq the U.S. risks being emasculated by the Iranians, who are swinging their big dicks in the form of tanks, rockets, and so on.

And those primitive Iraqis: All they respect is military force, right? If that’s so, why don’t they love America? After all, no country has “courageously” bombed them more over the last 25 years.

Talk about projection! Maybe it’s not the Iraqis or other unnamed Middle Easterners who are enthralled by “courage on the battlefield.” Maybe it’s all those “American sniper” wannabees, especially in Congress.

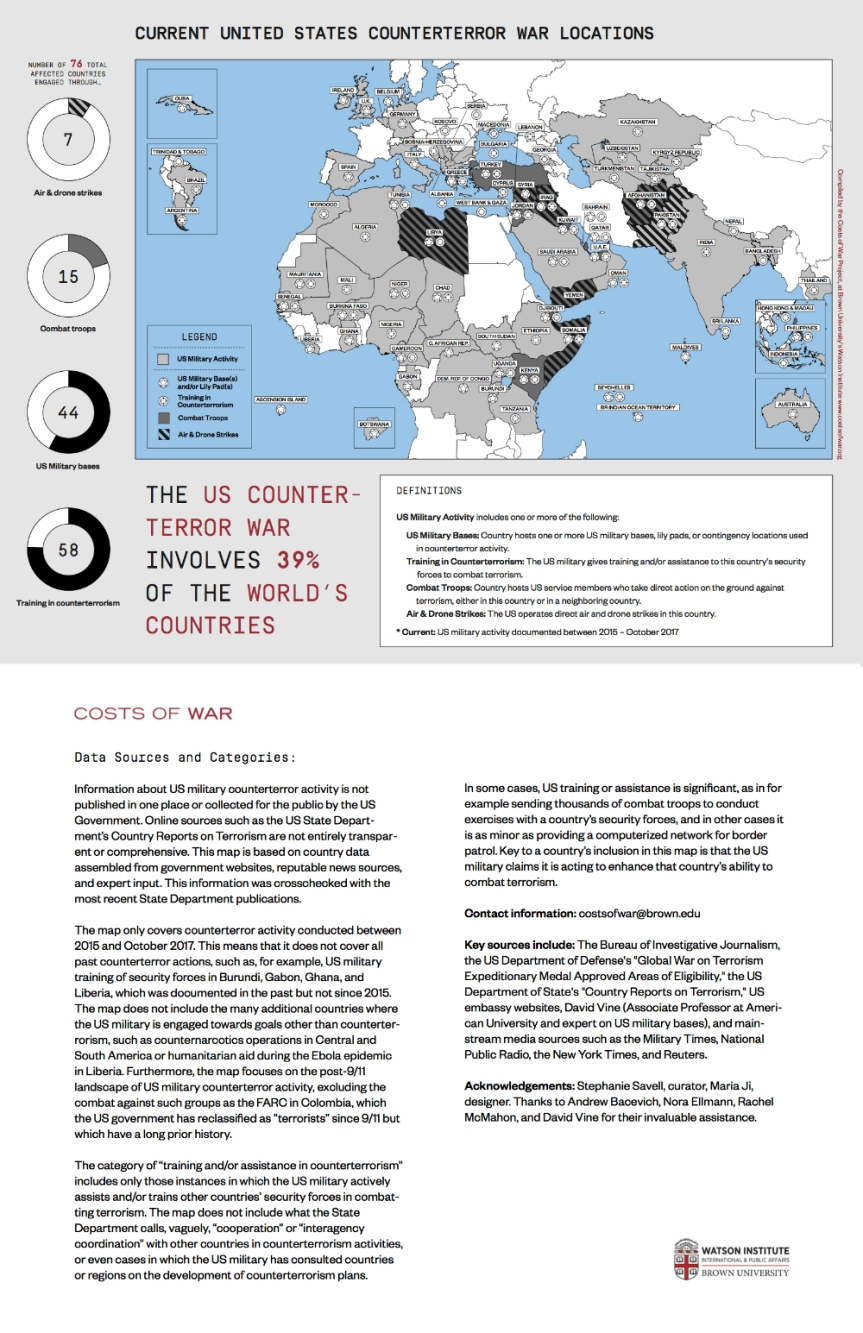

Consistent with Members of Congress clamoring for more war, America’s real ambassadors today are special forces and the special ops “community.” As Nick Turse noted for TomDispatch.com:

During the fiscal year that [started on October 1, 2013 and] ended on September 30, 2014, U.S. Special Operations forces (SOF) deployed to 133 countries — roughly 70% of the nations on the planet — according to Lieutenant Colonel Robert Bockholt, a public affairs officer with U.S. Special Operations Command (SOCOM). This capped a three-year span in which the country’s most elite forces were active in more than 150 different countries around the world, conducting missions ranging from kill/capture night raids to training exercises. And this year could be a record-breaker. Only a day before the failed raid that ended Luke Somers life — just 66 days into fiscal 2015 — America’s most elite troops had already set foot in 105 nations, approximately 80% of 2014’s total.”

As the U.S. deploys its special ops forces around the planet, part of their mission, stated or unstated, is to encourage foreign military sales (FMS in the trade). Naturally, in selling weapons to various “allies” around the world, the United States continues to dominate the world’s arms trade, a lead that we’re supposed to keep until the year 2021. Think about it. What other sector of industrial manufacturing will the U.S. dominate for the next seven years?

Here’s an excerpt from the Grimmett Report (2012) that tracks weapons sales around the globe. Note that U.S. dominance of the global arms trade has come under a Democratic president who was awarded a Nobel Peace Prize:

Recently, from 2008 to 2011, the United States and Russia have dominated the arms market in the developing world, with both nations either ranking first or second for each of these four years in the value of arms transfer agreements. From 2008 to 2011, the United States made nearly $113 billion in such agreements, 54.5% of all these agreements (expressed in current dollars). Russia made $31.1 billion, 15% of these agreements. During this same period, collectively, the United States and Russia made 69.5% of all arms transfer agreements with developing nations, ($207.3 billion in current dollars) during this four-year period. In 2011, the United States ranked first in arms transfer agreements with developing nations with over $56.3 billion or 78.7% of these agreements, an extraordinary increase in market share from 2010, when the United States held a 43.6% market share. In second place was Russia with $4.1 billion or 5.7% of such agreements. In 2011, the United States ranked first in the value of arms deliveries to developing nations at $10.5 billion, or 37.6% of all such deliveries. Russia ranked second in these deliveries at $7.5 billion or 26.8%.”

When it comes to deploying troops to foreign countries or to selling weapons overseas, the U.S. is indeed Number One. And that is precisely the problem. Troops and weapons do not spread freedom. Troops are trained to fight wars; they are trained to kill. Weapons are designed to kill. It’s a foreign policy based on a readiness — a willingness — perhaps even an eagerness — to kill.

For U.S. foreign policy, our national security state has reached one clear conclusion: the sword is mightier (and far more profitable) than the pen. Sorry, Thomas Jefferson.

The Pentagon is unable to account for more than $500 million in U.S. military aid given to Yemen, amid fears that the weaponry, aircraft and equipment is at risk of being seized by Iranian-backed rebels or al-Qaeda, according to U.S. officials.With Yemen in turmoil and its government splintering, the Defense Department has lost its ability to monitor the whereabouts of small arms, ammunition, night-vision goggles, patrol boats, vehicles and other supplies donated by the United States. The situation has grown worse since the United States closed its embassy in Sanaa, the capital, last month and withdrew many of its military advisers.

In recent weeks, members of Congress have held closed-door meetings with U.S. military officials to press for an accounting of the arms and equipment. Pentagon officials have said that they have little information to go on and that there is little they can do at this point to prevent the weapons and gear from falling into the wrong hands.

“We have to assume it’s completely compromised and gone,” said a legislative aide on Capitol Hill who spoke on the condition of anonymity because of the sensitivity of the matter.

U.S. military officials declined to comment for the record. A defense official, speaking on the condition of anonymity under ground rules set by the Pentagon, said there was no hard evidence that U.S. arms or equipment had been looted or confiscated. But the official acknowledged that the Pentagon had lost track of the items.

“Even in the best-case scenario in an unstable country, we never have 100 percent accountability,” the defense official said.

Yemen’s government was toppled in January by Shiite Houthi rebels who receive support from Iran and have strongly criticized U.S. drone strikes in Yemen. The Houthis have taken over many Yemeni military bases in the northern part of the country, including some in Sanaa that were home to U.S.-trained counterterrorism units. Other bases have been overrun by fighters from al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.

As a result, the Defense Department has halted shipments to Yemen of about $125 million in military hardware that were scheduled for delivery this year, including unarmed ScanEagle drones, other types of aircraft and Jeeps. That equipment will be donated instead to other countries in the Middle East and Africa, the defense official said.

Although the loss of weapons and equipment already delivered to Yemen would be embarrassing, U.S. officials said it would be unlikely to alter the military balance of power there. Yemen is estimated to have the second-highest gun ownership rate in the world, ranking behind only the United States, and its bazaars are well stocked with heavy weaponry. Moreover, the U.S. government restricted its lethal aid to small firearms and ammunition, brushing aside Yemeni requests for fighter jets and tanks.

In Yemen and elsewhere, the Obama administration has pursued a strategy of training and equipping foreign militaries to quell insurgencies and defeat networks affiliated with al-Qaeda. That strategy has helped to avert the deployment of large numbers of U.S. forces, but it has also met with repeated challenges.

Washington spent $25 billion to re-create and arm Iraq’s security forces after the 2003 U.S.-led invasion, only to see the Iraqi army easily defeated last year by a ragtag collection of Islamic State fighters who took control of large parts of the country. Just last year, President Obama touted Yemen as a successful example of his approach to combating terrorism.

“The administration really wanted to stick with this narrative that Yemen was different from Iraq, that we were going to do it with fewer people, that we were going to do it on the cheap,” said Rep. Mac Thornberry (R-Tex.), chairman of the House Armed Services Committee. “They were trying to do with a minimalist approach because it needed to fit with this narrative . . .that we’re not going to have a repeat of Iraq.”

Auditors with the Government Accountability Office found that Humvees donated to the Yemeni Interior Ministry sat idle or broken because the Defense Ministry refused to share spare parts. (Government Accountability Office)

Auditors with the Government Accountability Office found that Humvees donated to the Yemeni Interior Ministry sat idle or broken because the Defense Ministry refused to share spare parts. (Government Accountability Office)Washington has supplied more than $500 million in military aid to Yemen since 2007 under an array of Defense Department and State Department programs. The Pentagon and CIA have provided additional assistance through classified programs, making it difficult to know exactly how much Yemen has received in total.

U.S. government officials say al-Qaeda’s branch in Yemen poses a more direct threat to the U.S. homeland than any other terrorist group. To counter it, the Obama administration has relied on a combination of proxy forces and drone strikes launched from bases outside the country.

As part of that strategy, the U.S. military has concentrated on building an elite Yemeni special-operations force within the Republican Guard, training counterterrorism units in the Interior Ministry and upgrading Yemen’s rudimentary air force.

Making progress has been difficult. In 2011, the Obama administration suspended counterterrorism aid and withdrew its military advisers after then-President Ali Abdullah Saleh cracked down against Arab Spring demonstrators. The program resumed the next year when Saleh was replaced by his vice president, Abed Rabbo Mansour Hadi, in a deal brokered by Washington.

In a 2013 report, the U.S. Government Accountability Office found that the primary unclassified counterterrorism program in Yemen lacked oversight and that the Pentagon had been unable to assess whether it was doing any good.

Among other problems, GAO auditors found that Humvees donated to the Yemeni Interior Ministry sat idle or broken because the Defense Ministry refused to share spare parts. The two ministries also squabbled over the use of Huey II helicopters supplied by Washington, according to the report.

A senior U.S. military official who has served extensively in Yemen said that local forces embraced their training and were proficient at using U.S. firearms and gear but that their commanders, for political reasons, were reluctant to order raids against al-Qaeda.

“They could fight with it and were fairly competent, but we couldn’t get them engaged” in combat, the military official said, speaking on the condition of anonymity because he was not authorized to speak with a reporter.

All the U.S.-trained Yemeni units were commanded or overseen by close relatives of Saleh, the former president. Most were gradually removed or reassigned after Saleh was forced out in 2012. But U.S. officials acknowledged that some of the units have maintained their allegiance to Saleh and his family.

According to an investigative report released by a U.N. panel last month, the former president’s son, Ahmed Ali Saleh, looted an arsenal of weapons from the Republican Guard after he was dismissed as commander of the elite unit two years ago. The weapons were transferred to a private military base outside Sanaa that is controlled by the Saleh family, the U.N. panel found.

It is unclear whether items donated by the U.S. government were stolen, although Yemeni documents cited by the U.N. investigators alleged that the stash included thousands of M-16 rifles, which are manufactured in the United States.

The list of pilfered equipment also included dozens of Humvees, Ford vehicles and Glock pistols, all of which have been supplied in the past to Yemen by the U.S. government. Ahmed Saleh denied the looting allegations during an August 2014 meeting with the U.N. panel, according to the report.

Many U.S. and Yemeni officials have accused the Salehs of conspiring with the Houthis to bring down the government in Sanaa. At Washington’s urging, the United Nations imposed financial and travel sanctions in November against the former president, along with two Houthi leaders, as punishment for destabilizing Yemen.

Ali Abdullah Saleh has dismissed the accusations; last month, he told The Washington Post that he spends most of his time these days reading and recovering from wounds he suffered during a bombing attack on the presidential palace in 2011.

There are clear signals that Saleh and his family are angling for a formal return to power. On Friday, hundreds of people staged a rally in Sanaa to call for presidential elections and for Ahmed Saleh to run.

Although the U.S. Embassy in the capital closed last month, a handful of U.S. military advisers have remained in the southern part of the country at Yemeni bases controlled by commanders that are friendly to the United States.

Craig Whitlock covers the Pentagon and national security. He has reported for The Washington Post since 1998.