W.J. Astore

I was on active duty in the military for twenty years. My experience: It’s very difficult to see the big picture in the military. The everyday pressures of the mission keep you focused on the short term. I recall writing many WARs (weekly activity reports) and being focused on the immediate. Even the yearly budgetary process tends to keep you focused on the short term. Assignments for officers and enlisted rarely last longer than three years, with combat tours typically much shorter. Personnel are constantly changing: for one acquisition project I worked on, four program managers (colonels) rotated in and out in three years.

Along with being focused on the immediate, you are actively discouraged from criticizing the system in any fundamental way. Of course, you’re not supposed to criticize the commander-in-chief, you’re not supposed to be insubordinate to your chain of command, you’re not supposed to undermine morale. At the same time, one mistake can be deadly to a career. People in the military therefore tend to play it safe. Doubters tend to conform. They shut their mouths. Or they vote with their feet by leaving the military.

Critics with the best of intentions often get squashed. Consider the Air Force pilot who found a problem with the F-22 Raptor’s cockpit oxygen supply system. This was a top priority, safety of flight, issue, but the Air Force played down the problem so as to protect procurement for the Raptor. The pilot eventually complained to CBS “60 Minutes” and saw his career stall as a result. Or consider General Eric Shinseki, who as Army Chief of Staff had the temerity to disagree with the Bush Administration’s rosy talk of low troop requirements in the wake of the invasion of Iraq in 2003. Shinseki was shunted aside by a system that had no room for well-informed dissent.

Pressures to conform and short-term planning and personnel cycles combine to produce mediocrity and to reproduce the past. John Paul Vann, an expert on the Vietnam War who died in that war, noted the U.S. military didn’t have 12 years’ experience in Vietnam: it had one years’ experience repeated 12 times over. Something similar is true in Afghanistan today: the U.S. doesn’t have 14 years’ experience fighting the Taliban and building Afghan security forces, but rather one years’ experience repeated 14 times.

U.S. military actions are sequential rather than synergistic. It’s just one damn thing after another. The reality of this is often seen more clearly by people who are outside of the military. Outsiders aren’t caught up in everyday pressures or limited by conformism. They’re not caught in a Pentagonal box in which misguided tactics and mistaken goals are accepted by insiders as SOP – standard operating procedure.

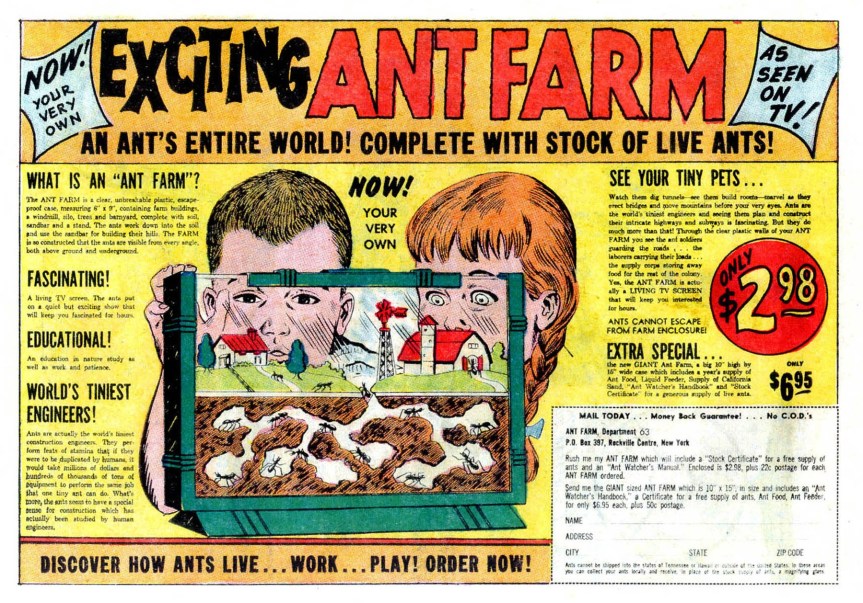

But perhaps “box” is the wrong image for the Pentagon and its unreflective busyness; ant farm might be better. If you’re of a certain age, you may remember those old ant farms advertised in the back pages of comic books. You could send away for a see-through container with sand and ants that allowed you to watch as your crew of ants busily worked away in your “farm.”

Today’s Pentagon reminds me of those old ant farms. The ants work busily within it. Anyone watching wouldn’t question their dedication. Yet as you’re standing outside the farm, watching them, you can see how tightly their world is delimited and circumscribed. What is obvious to you is simply beyond them. The ants keep digging in and rolling along.

It’s well worth asking why the U.S. military puts so much pride on working to the point of exhaustion. A friend of mine worked at the Pentagon. He worked hard during his normal shift – but he left on-time to go home. His co-workers, noses to the grindstone, would hassle him about leaving “early.” He’d reply: I can leave on-time because I didn’t spend hours rotating between the coffee maker and the gym.

A mindless emphasis on over-caffeinated work and fitness, as another friend suggested, may be a post-Vietnam War reaction to the McNamara “managerial” culture of the 1960s. As he put it, “One easy way of showing one has the right stuff is to be an exercise nut, and the penumbras of that mind-set have really distorted the allocation of effort in our military.” Recall that General David Petraeus made a moral fetish out of personal fitness and how that indirectly cost him his career (he made his initial connection to his mistress/biographer while running together). Recall that General Stanley McChrystal was celebrated for his fitness regimen, which didn’t convey the smarts to rein in the insubordinate behavior of his men.

One more anecdote about incessant “army ant” work. A Vietnam veteran told me this story about mindless work for the sake of show:

“One feature of my first Vietnam unit epitomized all this to me: the trucks in our motor pool were perfectly lined up. I don’t know how they did it. Must have had squads of soldiers pushing them to just the right spot then stuck chocks under the wheels to keep them there. The 4-star-corps commander used to drive by our motor pool frequently to go to USARV HQ. He never stopped to see if the trucks were drivable. They were not. Almost all deadlined.”

Lots of busy-work down on the ant farm may look good from a distance, but it does not produce victory.

Today’s U.S. military has its enemies outgunned. There’s little wrong with its work ethic. What the U.S. military hasn’t done is to outthink its enemies. Indeed, the military’s actions often conspire to create new ones. To admit this is not to place the blame entirely on the military. Its civilian leaders have to shoulder blame as well. But ultimately it’s the military that advises the president and Congress, and I haven’t witnessed senior military officers resigning because their advice hasn’t been followed.

If the U.S. military is to be reformed, you can’t look to the ants to do it. They’re too busy keeping the system running. We must look beyond the farm, to outsiders who are able and willing to think freely. Yet the military too needs to act, if for no other reason than to end a miserable run of defeats (or pyrrhic victories, if that sounds less harsh). Rather than simply promoting loyal and hardworking ants, it needs to foster seers and thinkers – people willing to buck the system.

It won’t be easy – but it’s sure better than losing.

For the ever-expanding, resource-devouring, never-accountable U.S. military, nothing succeeds like failure; or, put another way: nothing wins like losing. I have said for many years now that George Orwell’s famous three slogans of the party — Ignorance is Strength, Freedom is Slavery, War is Peace — required the addition of a fourth flagrantly oxymoronic credo, courtesy of the the post-WWII U.S. military and the corporate war-profiteers it services so shamelessly. Thankfully, the Russian ex-patriate engineer Dmitry Orlov has also seen the glaringly obvious truth about U.S. military bungling and has entertainingly described it in a recent essay. See, Defeat Is Victory, by Dmitry Orlov, Club Orlov (Tuesday, January 19, 2016).

So, onward and downward to our next profitable defeat. Right, fellow Crimestoppers?

LikeLike

… and the rats keep winning the rat race.

*sigh*

LikeLike

Pride might be the greatest problem for the US military. Unfortunately this pride is in small things like lined up trucks and separate service histories and the latest technology. This is the pride of peace-time soldiers instead of effective fighters. Where is the interest in effectiveness appropriate to being prepared for actual combat?

We have known for decades that US forces are inefficiently organized, but pride keeps musket and sailboat era chains of command [and resource competition] in a drone and satellite world.

The solution begins with Congress eliminating committees with special interests in individual services. Hearings need to include critiques from foreign and academic military experts with no service careers at stake. Reward US officers who find ways to reduce costs, to do more with less, by giving them senior civilian DoD assignments where their careers are not limited by the service culture and they can continue the work for which they have shown an aptitude.

The service academies also perpetuate specific cultures of pride. The academies provide engineering training which is now widely available. Even academy graduates get their military-specific training through later officer schools and war colleges. These hothouses with their strong elements of multi-generational insiders have internal and juvenile customs which further lock people into relationships and dominate the services, blocking out different points of view.

In this air age, overseas bases can be staffed by units sent on six month tours instead of individuals sent to changed stations.

Combat is conducted by enlisted troops. Officer positions create ancillary costs in terms of officer status privileges. Measure the ratio of officers to enlisted and compare this to historic and worldwide statistics to find target levels. We don’t need officer positions to attract pilots. If there is a civil service and military officer overlap in chief/deputy slots, then delete the military slot and reduce the total number of officers by one. Has anyone looked at reducing the size of the personal staffs of senior officers since automobiles and washing machines and computers made it possible to do more with fewer people?

Combat liability justifies military pension and wage rates. Cutting the budget means looking to eliminate non-combat positions. Eliminate as many as possible non-combat military specialties. Improve the tooth to tail ratio. Eliminate the slots, not just certain organizations.

Non-competing services means less need for military demonstration organizations of fliers, jumpers, bands. Modern combat does not need close order drill or musicians to pace it. Eliminate all military provided conveniences to the President now hidden in the Pentagon budget. Aspire to be a lean, mean, fighting machine with few other institutional distractions.

We need to use some cost-effectiveness ideas in evaluating US military forces instead of spreading so much pride.

LikeLike

And as the Good Book says, “Pride goeth before destruction …”

LikeLike

Bill.

Foster people willing to buck the system. Not in the genes, as you know.

LikeLike

How true, Walt. Do you own the stars, or do the stars own you? For too many of our generals, it’s the latter. The stars own them, and all they want is more stars.

LikeLike

Bill.

It is my experience that National Guard generals, particularly those who were “part time,” among all generals, were those most likely to buck the federal system – it is in our militia genes, and always has been. However, as the Guards are increasingly dominated by leaders who owe their entire income to it – what we call full-timers – these voices have all but disappeared.

Ironically, the system itself crushes us because the best part-time Guard officers are also those most in demand in the private sector. Ask too much time off to meet military education requirements, for example, and you are likely to be looking for a new job. I did the advanced course and staff college entirely by correspondence, and was promoted to flag without being a senior service college graduate. These options are no longer available.

LikeLike