W.J. Astore

William Westmoreland (“Westy”) looked like a general should, and that was part of the problem. Tall, handsome, square-jawed, he carried himself rigidly; there was no slouching for Westy. A go-getter, a hard-charger, he did everything necessary to get promoted. He was a product of the Army, a product of a system that began at West Point during World War II and ended with four stars and command in Vietnam during the most critical years of that war (1965-68). His unimaginative and mediocre performance in a losing effort said (and says) much about that system.

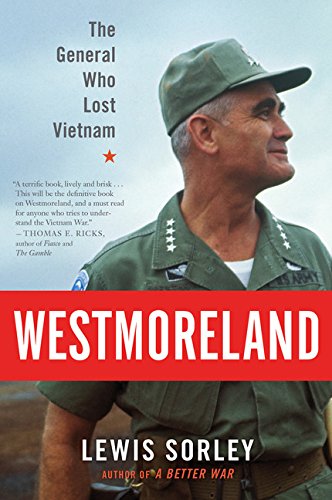

I had these thoughts as I read Lewis Sorley’s devastating biography of Westy, recommended to me by a good friend. (Thanks, Paul!) Before tackling the big stuff about Westy, the Army, and Vietnam, I’d like to focus on little things that stayed with me as I read the book.

- Visiting West Point as the Army’s Chief of Staff, Westy met the new First Captain, the highest-ranking cadet. Westy thought this cadet wasn’t quite tall enough to be First Captain. It made me wonder whether Napoleon might have won Waterloo if he’d been as tall as Westy.

- Westy loved uniforms and awards. Sporting an impressive array of ribbons, badges, devices, and the like, his busy uniform was consistent with his concern for outward show, for image and action over substance and meaning.

- Westy tended to focus on the trivial. He’d visit lower commands and ask junior officers whether the troops were getting their mail (vital for morale, he thought). He’d ask narrow technical questions about mortars versus artillery performance. He was a details man in a position that required a much broader sweep of mind.

- Westy liked to doodle, including drawing the rank of a five-star general. He arguably saw himself as destined to this rank, following in the hallowed steps of Douglas MacArthur, Dwight Eisenhower, and Omar Bradley.

- Westy never attended professional military education (PME), such as the Army War College, and he showed little interest in books. He was incurious and rather proud of it.

Interestingly, Sorley cites another general who argued Westy’s career should have ended as a regimental colonel. Others believed he served adequately as a major general in command of a division. Above this rank, Westy was, some of his fellow officers agreed, out his depth.

Sorley depicts Westy as an unoriginal and conventional thinker for a war that was unconventional and complex. Bewildered by Vietnam, Westy fell back to what he (and the Army) knew best: massive firepower, search and destroy tactics, and made-up metrics like “body count” as measures of “success.” He tried to win a revolutionary war using a strategy of attrition, paying little attention to political dimensions. For example, he shunted the South Vietnamese military (ARVN) to the side while giving them inferior weaponry to boot.

Another personal weakness: Westy didn’t respond well to criticism. When General Douglas Kinnard published his classic study of the Vietnam War, “The War Managers,” which surveyed senior officers who’d served in Vietnam, Westy wanted him to tattle on those officers who’d objected to his pursuit of body count. (Kinnard refused.)

Sorley identifies Westmoreland as the general who lost Vietnam, and there’s truth in that. Deeply flawed, Westy’s strategy was fated to fail. Yet even the most skilled American general may have lost in Vietnam. Consider here the words of President Lyndon B. Johnson in the middle of 1964. He told McGeorge Bundy “It looks to me like we’re getting’ into another Korea…I don’t think it’s worth fightin’ for and I don’t think we can get out. It’s just the biggest damn mess…What the hell is Vietnam worth to me?…What is it worth to this country?” [Quoted in Robert Dallek, “Three New Revelations About LBJ,” The Atlantic, April 1998]

McGeorge Bundy himself, LBJ’s National Security Adviser, said to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara that committing large numbers of U.S. troops to Vietnam was “rash to the point of folly.” In October 1964 his brother William Bundy, then the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, said in a confidential memorandum that Vietnam was “A bad colonial heritage of long standing…a nationalist movement taken over by Communism ruling in the other half of an ethnically and historically united country, the Communist side inheriting much the better military force and far more than its share of the talent—these are the facts that dog us today.”

Not worth fighting for, rash to the point of folly: Why did the U.S. go to war in Vietnam when the cause was arguably lost before the troops were committed? Traditional answers include the containment of communism, the domino theory, American overconfidence, and so forth, but perhaps there was a larger purpose to the “folly.”

What was that larger purpose? I recall a “letter to the editor” that I clipped from a newspaper years ago. Echoing a critique made by Noam Chomsky,** this letter argued America’s true strategic aim in Vietnam was to prevent Vietnam’s independent social and economic development; to subjugate and/or subordinate Vietnam and its resources to the whims of Western corporations and investors. Winning on the battlefield was less important than winning in the global marketplace. Vietnam would send a loud signal to other countries that, if you tried to chart your own course independent of American interests, you’d end up like Vietnam, a battlefield, a wasteland.

For sure, Westy lost on the battlefield. But did U.S. economic interests triumph globally due to his punishment of Vietnam and the intimidation it established? How compelling, how coercive, were such interests? Think of Venezuela today as it attempts to chart an independent course. Think of U.S. interest in subordinating Venezuela and its reserves of oil to the agendas of Western investors and corporations. There are trillions of dollars to be made here, not just from oil, but by preserving the strength of the petrodollar. (The U.S. dollar’s value is propped up by global oil sales done in dollars, as vouchsafed by leading oil producers like Saudi Arabia. Venezuela has acted against the petrodollar standard.)

Westy was the wrong man for Vietnam, but he was also a fall guy for a doomed war. He and the U.S. military did succeed, however, in visiting a level of destruction on that country that sent a message to those who contemplated resisting Western economic demands. Westy may have been a lousy general, but perhaps he was the perfect message boy for economic interests that prospered more by destruction and intimidation than by traditional victory of arms.

**For Chomsky, America didn’t accidentally or inadvertently or ham-fistedly destroy the Vietnamese village to save it; the village was destroyed precisely to destroy it, thereby strengthening capitalism and U.S. economic hegemony throughout the developing world. As General Smedley Butler said, sometimes generals are economic hit men, even when they don’t know it.

As a general rule, it’s a lot easier in U.S. politics to sell a war as containing or defeating communist aggression (or radical Islamic terrorism in the case of Iran, or ruthless dictators in the cases of Iraq and Libya) than it is for economic interests and the profits of powerful multinational corporations. For the average grunt, “Remember Exxon-Mobil!” isn’t much of a battle-cry.