W.J. Astore

On Ending Militarism in America

Also at TomDispatch.com

I read the news today, oh boy. About a lucky man named Elon Musk. But he lost out on one thing: he didn’t get a top secret briefing on Pentagon war plans for China. And the news people breathed a sigh of relief.

With apologies to John Lennon and The Beatles, a day in the life is getting increasingly tough to take here in the land of the free. I’m meant to be reassured that Musk didn’t get to see America’s top-secret plans for — yes! — going to war with China, even as I’m meant to ignore the constant drumbeat of propaganda, the incessant military marches that form America’s background music, conveying the message that America must have war plans for China, that indeed war in or around China is possible, even probable, in the next decade. Maybe in 2027?

My fellow Americans, we should be far more alarmed by such secret U.S. war plans, along with those “pivots” to Asia and the Indo-Pacific, and the military base-building efforts in the Philippines, than reassured by the “good news” that Comrade Billionaire Musk was denied access to the war room, meaning (for Dr. Strangelove fans) he didn’t get to see “the big board.”

It’s war, war, everywhere in America. We do indeed have a strange love for it. I’ve been writing for TomDispatch for 18 years now — this is my 111th essay (the other 110 are in a new book of mine) — most of them focusing on militarism in this country, as well as our disastrous wars in Iraq, Afghanistan, and elsewhere, the ruinous weapons systems we continue to fund (including new apocalyptic nuclear weapons), and the war song that seems to remain ever the same.

A few recent examples of what I mean: President Trump has already bombed Yemen more than once. He’s already threatening Iran. He’s sending Israel all the explosives, all the weaponry it needs to annihilate the Palestinians in Gaza (so too, of course, did Joe Biden). He’s boasting of building new weapons systems like the Air Force’s much-hyped F-47 fighter jet, the “47” designation being an apparent homage by its builder, Boeing, to Trump himself, the 47th president. He and his “defense” secretary, Pete Hegseth, continually boast of “peace through strength,” an Orwellian construction that differs little from “war is peace.” And I could, of course, go on and on and on and on…

Occasionally, Trump sounds a different note. When Tulsi Gabbard became the director of national intelligence, he sang a dissonant note about a “warmongering military-industrial complex.” And however haphazardly, he does seem to be working for some form of peace with respect to the Russia-Ukraine War. He also talks about his fear of a cataclysmic nuclear war. Yet, if you judge him by deeds rather than words, he’s just another U.S. commander-in-chief enamored of the military and military force (whatever the cost, human or financial).

Consider here the much-hyped Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) led by that lucky man Elon Musk. Even as it dismantles various government agencies like the Department of Education and USAID, it has — no surprise here! — barely touched the Pentagon and its vast, nearly trillion-dollar budget. In fact, if a Republican-controlled Congress has any say in the matter, the Pentagon budget will likely be boosted significantly for Fiscal Year 2026 and thereafter. As inefficient as the Pentagon may be (and we really don’t know just how inefficient it is, since the bean counters there keep failing audit after audit, seven years running), targeted DOGE Pentagon cuts have been tiny. That means there’s little incentive for the generals to change, streamline their operations, or even rethink in any significant fashion. It’s just spend, spend, spend until the money runs out, which I suppose it will eventually, as the national debt soars toward $37 trillion and climbing.

Even grimmer than that, possibly, is America’s state of mind, our collective zeitgeist, the spirit of this country. That spirit is one in which a constant state of war (and preparations for more of the same) is accepted as normal. War, to put it bluntly, is our default state. It’s been that way since 9/11, if not before then. As a military historian, I’m well aware that the United States is, in a sense, a country made by war. It’s just that today we seem even more accepting of that reality, or resigned to it, than we’ve ever been. What gives?

Remember when, in 1963, Alabama Governor George Wallace said, “Segregation now, segregation tomorrow, and segregation forever”? Fortunately, after much struggle and bloodshed, he was proven wrong. So, can we change the essential American refrain of war now, war tomorrow, and war forever? Can we render that obsolete? Or is that too much to hope for or ask of America’s “exceptional” democracy?

Taking on the MICIMATT(SH)

Former CIA analyst Ray McGovern did America a great service when he came up with the acronym MICIMATT, or the Military-Industrial-Congressional-Intelligence-Media-Academia-Think-Tank complex, an extension of President Dwight D. Eisenhower’s military-industrial complex, or MIC (from his farewell speech in 1961). Along with the military and industry (weapons makers like Boeing and Lockheed Martin), the MICIMATT adds Congress (which Eisenhower had in his original draft speech but deleted in the interest of comity), the intelligence “community” (18 different agencies), the media (generally highly supportive of wars and weapons spending), academia (which profits greatly from federal contracts, especially research and development efforts for yet more destructive weaponry), and think tanks (which happily lap up Pentagon dollars to tell us the “smart” position is always to prepare for yet more war).

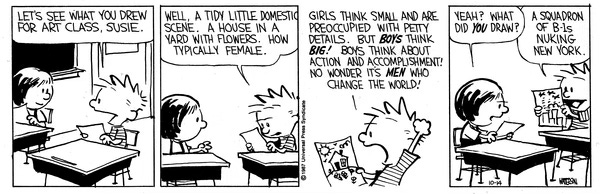

You’ll note, however, that I’ve added a parenthetical SH to McGovern’s telling acronym. The S is for America’s sporting world, which eternally gushes about how it supports and honors America’s military, and Hollywood, which happily sells war as entertainment (perhaps the best known and most recent film being Tom Cruise’s Top Gun: Maverick, in which an unnamed country that everyone knows is Iran gets its nuclear ambitions spanked by a plucky team of U.S. Naval pilots). A macho catchphrase from the original Top Gun was “I feel the need — the need for speed!” It may as well have been: I feel the need — the need for pro-war propaganda!

Yes, MICIMATT(SH) is an awkward acronym, yet it has the virtue of capturing some of the still-growing power, reach, and cultural penetration of Ike’s old MIC. It should remind us that it’s not just the military and the weapons-makers who are deeply invested in war and — yes! — militarism. It’s Congress; the CIA; related intel “community” members; the mainstream media (which often relies on retired generals and admirals for “unbiased” pro-war commentary); academia (consider how quickly institutions like Columbia University have bent the knee to Trump); and think tanks — in fact, all those “best and brightest” who advocate for war with China, the never-ending war on terror, war everywhere.

But perhaps the “soft power” of the sporting world and Hollywood is even more effective at selling war than the hard power of bombs and bullets. National Football League coaches patrol the sidelines wearing camouflage, allegedly to salute the troops. Military flyovers at games celebrate America’s latest death-dealing machinery. Hollywood movies are made with U.S. military cooperation and that military often has veto power over scripts. To cite only one example, the war movie 12 Strong (2018) turned the disastrous Afghan War that lasted two horrendous decades into a stunningly quick American victory, all too literally won by U.S. troops riding horses. (If only the famed cowboy actor John Wayne had still been alive to star in it!)

The MICIMATT(SH), employing millions of Americans, consuming trillions of dollars, and churning through tens of thousands of body bags for U.S. troops over the years, while killing millions of people abroad, is an almost irresistible force. And right now, it seems like there’s no unmovable object to blunt it.

Believe me, I’ve tried. I’ve written dozens of “Tomgrams” suggesting steps America could take to reverse militarism and warmongering. As I look over those essays, I see what still seem to me sensible ideas, but they die quick deaths in the face of, if not withering fire from the MICIMATT(SH), then being completely ignored by those who matter.

And while this country has a department of war (disguised as a department of defense), it has no department of peace. There’s no budget anywhere for making peace, either. We do have a colossal Pentagon that houses 30,000 workers, feverishly making war plans they won’t let Elon Musk (or any of us) see. It’s for their eyes only, not yours, though they may well ask you or your kids to serve in the military, because the best-laid plans of those war-men do need lots of warm bodies, even if those very plans almost invariably (Vietnam, Afghanistan, Iraq, etc.) go astray.

So, to repeat myself, how do you take on the MICIMATT(SH)? The short answer: It’s not easy, but I know of a few people who had some inspirational ideas.

On Listening to Ike, JFK, MLK, and, Yes, Madison, Too

Militarism isn’t exactly a new problem in America. Consider Randolph Bourne’s 1918 critique of war as “the health of the state,” or General Smedley Butler’s confession in the 1930s that “war is a racket” run by the “gangsters of capitalism.” In fact, many Americans have, over the years, spoken out eloquently against war and militarism. Many beautiful and moving songs have asked us to smile on your brother and “love one another right now.” War, as Edwin Starr sang so powerfully once upon a time, is good for “absolutely nothin’,” though obviously a lot of people disagree and indeed are making a living by killing and preparing for yet more of it.

And that is indeed the problem. Too many people are making too much money off of war. As Smedley Butler wrote so long ago: “Capital won’t permit the taking of the profit out of war until the people — those who do the suffering and still pay the price — make up their minds that those they elect to office shall do their bidding, and not that of the profiteers.” Pretty simple, right? Until you realize that those whom we elect are largely obedient to the moneyed class because the highest court in our land has declared that money is speech. Again, I didn’t say it was going to be easy. Nor did Butler.

As a retired lieutenant colonel in the U.S. Air Force, I want to end my 111th piece at TomDispatch by focusing on the words of Ike, John F. Kennedy (JFK), Martin Luther King, Jr. (MLK), and James Madison. And I want to redefine what words like duty, honor, country, and patriotism should mean. Those powerful words and sentiments should be centered on peace, on the preservation and enrichment of life, on tapping “the better angels of our nature,” as Abraham Lincoln wrote so long ago in his First Inaugural Address.

Why do we serve? What does our oath of office really mean? For it’s not just military members who take that oath but also members of Congress and indeed the president himself. We raise our right hands and swear to support and defend the U.S. Constitution against all enemies, foreign and domestic, to bear true faith and allegiance to the same.

There’s nothing in that oath about warriors and warfighters, but there is a compelling call for all of us, as citizens, to be supporters and defenders of representative democracy, while promoting the general welfare (not warfare), and all the noble sentiments contained in that Constitution. If we’re not seeking a better and more peaceful future, one in which freedom may expand and thrive, we’re betraying our oath.

If so, we have met the enemy — and he is us.

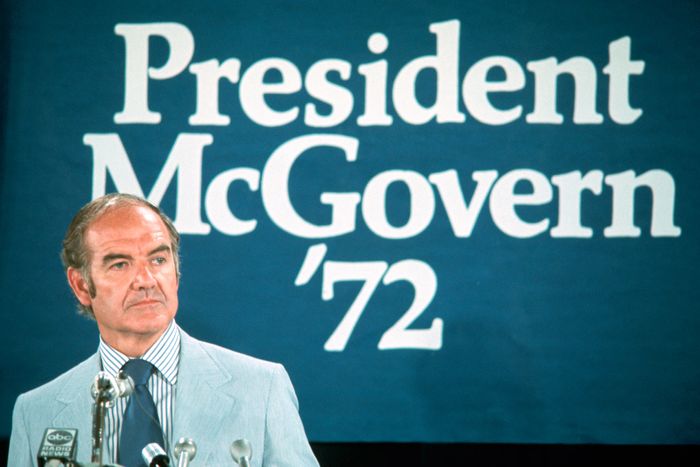

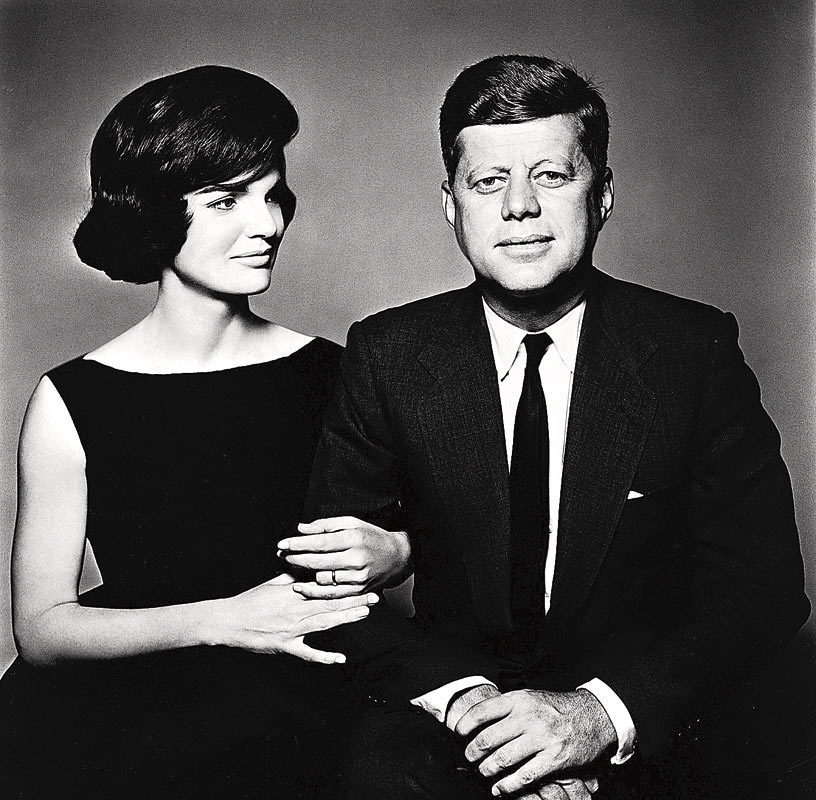

Ike told us in 1953 that constant warfare is no way of life at all, that it is (as he put it), humanity crucifying itself on a cross of iron. In 1961, he told us democracy was threatened by an emerging military-industrial complex and that we, as citizens, had to be both alert and knowledgeable enough to bring it to heel. Two years later, JFK told us that peace — even at the height of the Cold War — was possible, not just peace in our time, but peace for all time. However, it would, he assured us, require sacrifice, wisdom, and commitment.

How, in fact, can I improve on these words that JFK uttered in 1963, just a few months before he was assassinated?

What kind of peace do we seek? Not a Pax Americana enforced on the world by American weapons of war. Not the peace of the grave or the security of the slave. I am talking about genuine peace, the kind of peace that makes life on earth worth living…

I speak of peace because of the new face of war. Total war makes no sense in an age… when the deadly poisons produced by a nuclear exchange would be carried by wind and water and soil and seed to the far corners of the globe and to generations yet unborn… surely the acquisition of such idle [nuclear] stockpiles — which can only destroy and never create — is not the only, much less the most efficient, means of assuring peace.

I speak of peace, therefore, as the necessary rational end of rational men. I realize that the pursuit of peace is not as dramatic as the pursuit of war — and frequently the words of the pursuer fall on deaf ears. But we have no more urgent task.

Are we ready to be urgently rational, America? Are we ready to be blessed as peacemakers? Or are we going to continue to suffer from what MLK described in 1967 as our very own “spiritual death” due to the embrace of militarism, war, empire, and racism?

Of course, MLK wasn’t perfect, nor for that matter was JFK, who was far too enamored of the Green Berets and too wedded to a new strategy of “flexible response” to make a clean break in Vietnam before he was killed. Yet those men bravely and outspokenly promoted peace, something uncommonly rare in their time — and even more so in ours.

More than 200 years ago, James Madison warned us that continual warfare is the single most corrosive force to the integrity of representative democracy. No other practice, no other societal force is more favorable to the rise of authoritarianism and the rule of tyrants than pernicious war. Wage war long and it’s likely you can kiss your democracy, your rights, and just maybe your ass goodbye.

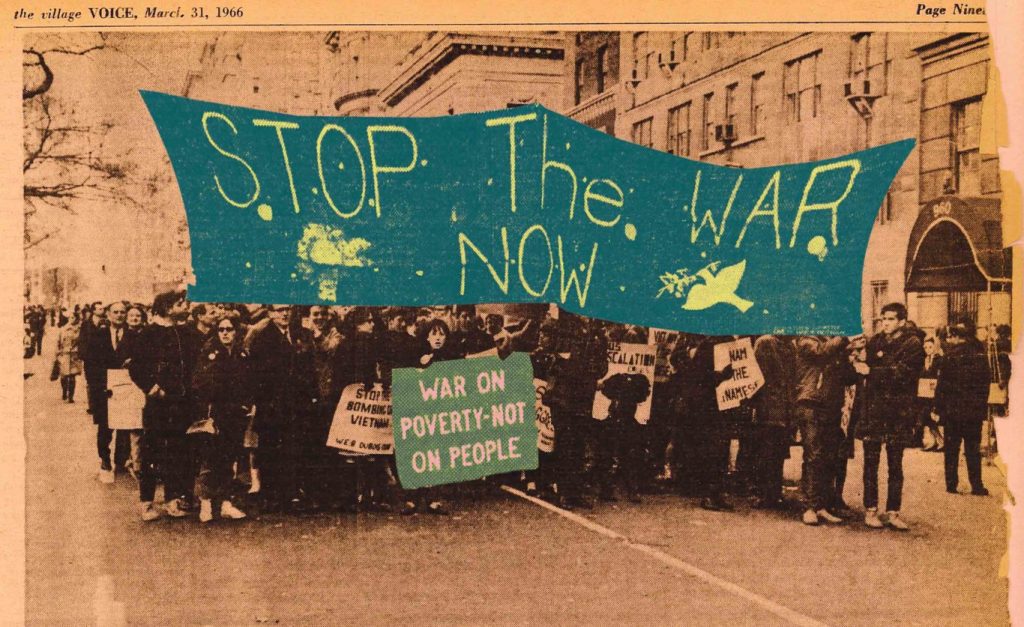

America, from visionaries and prophets like MLK, we have our marching orders. They are not to invest yet more in preparations for war, whether with China or any other country. Rather, they are to gather in the streets and otherwise raise our voices against the scourge of war. If we are ever to beat our swords into plowshares and our spears into pruning hooks and make war no more, something must be done.

Let’s put an end to militarism in America. Let’s be urgently rational. To cite John Lennon yet again: You may say I’m a dreamer, but I’m not the only one. Together, let’s imagine and create a better world.

Copyright 2025 William J. Astore.