W.J. Astore

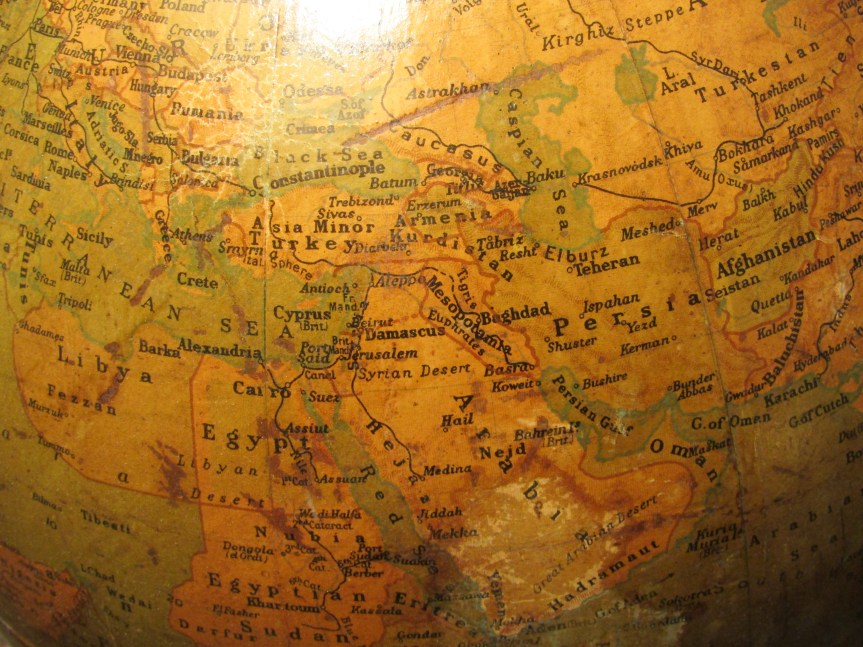

How about a contrary perspective on the Middle East, courtesy of my old globe? It dates from the early 1920s, just after World War I but before Russia became the Soviet Union. Taking a close look at the Middle East (a geographic term that I use loosely), you’ll notice more than a few differences from today’s maps and globes:

- Iraq and Syria don’t exist. Neither does Israel. Today’s Iran is yesterday’s Persia, of course.

- Instead of Iraq and Syria, we have Mesopotamia, a name that resonates history, part of the Fertile Crescent that encompassed the Tigris and Euphrates Rivers as well as the Nile in Egypt. Six thousand years ago, the cradle of human civilization, and now more often the scene of devastation caused mainly by endless war.

- Ah, Kurdistan! The Kurds today in northern Iraq and southern Turkey would love to have their own homeland. Naturally, the Arabs and Turks, along with the Persians, feel differently.

- Look closely and you’ll see “Br. Mand.” and “Fr. Mand.” With the collapse of the Ottoman Empire (roughly a larger version of modern-day Turkey) at the end of World War I, the British gained a mandate over Palestine and Mesopotamia and the French gained one over territory that would become Lebanon and Syria. The British made conflicting promises to Jews and Arabs over who would control Palestine while scheming to protect their own control over the Suez Canal. A large portion of Palestine, of course, was given to Jews after the Holocaust of World War II, marking the creation of Israel and setting off several Arab-Israeli Wars(1948-73) and the ongoing low-level war between Israel and the Palestinians, most bitterly over the status of the “Occupied Territories”: land captured by the Israelis during these wars, i.e. the West Bank (of the Jordan River) and the Gaza Strip (both not labeled on my outdated globe).

- Improvisation marked the creation of states such as Lebanon, Syria, and Iraq. Borders encapsulated diverse peoples with differing goals. Western powers like Britain and France cared little for tribal allegiances or Sunni/Shia sensitivities or political leanings, favoring autocratic rulers who could keep the diverse peoples who lived there in line.

- Historically powerful peoples with long memories border the Middle East. The Turks and the Persians (Iranians), of course, with Russians hovering in the near distance. They all remain players with conflicting goals in the latest civil war in Syria and the struggle against ISIS/ISIL.

- Three of the world’s “great” religions originated from a relatively tiny area of our globe: Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. Talk about a fertile crescent! Sadly, close proximity and shared roots did not foster tolerance: quite the reverse.

- Remember when Saudi Arabia was just Arabia? Ah, those were the good old days, Lawrence.

- Nobody talks much about Jordan, an oasis of relative calm in the area (not shown on my old globe). Lucky Jordan.

- The presence of Armenia in Turkey on my old globe raises all kinds of historical ghosts, to include the Armenian genocide of World War I. Today, Turkey continues to deny that the word “genocide” is appropriate to the mass death of Armenians during World War I.

My fellow Americans, one statement: The idea that America “must lead” in this area of the world speaks to our hubris and ignorance. We are obviously not seen as impartial. Our “leadership” is mainly expressed by violent military action.

But we just can’t help ourselves. The idea of “global reach, global power” is too intoxicating. We see the globe as ours to spin. Ours to control.

Perhaps old globes can teach us the transitory nature of power. After all, those British and French mandates are gone. European powers, however grudgingly, learned to retrench. (Of course, the British and French, together with the Germans, are now bombing and blasting old mandates in the name of combating terrorism.)

I wonder how a globe made in 2115 will depict this area of the world. Will it look like today’s globe, or more like my globe from c.1920, or something entirely different? Will it show a new regional empire or more fragmentation? An empire based on Islam or a shattered and blasted infertile crescent ravaged by war and an inhospitable climate driven by global warming?

Readers: I welcome your comments and predictions.