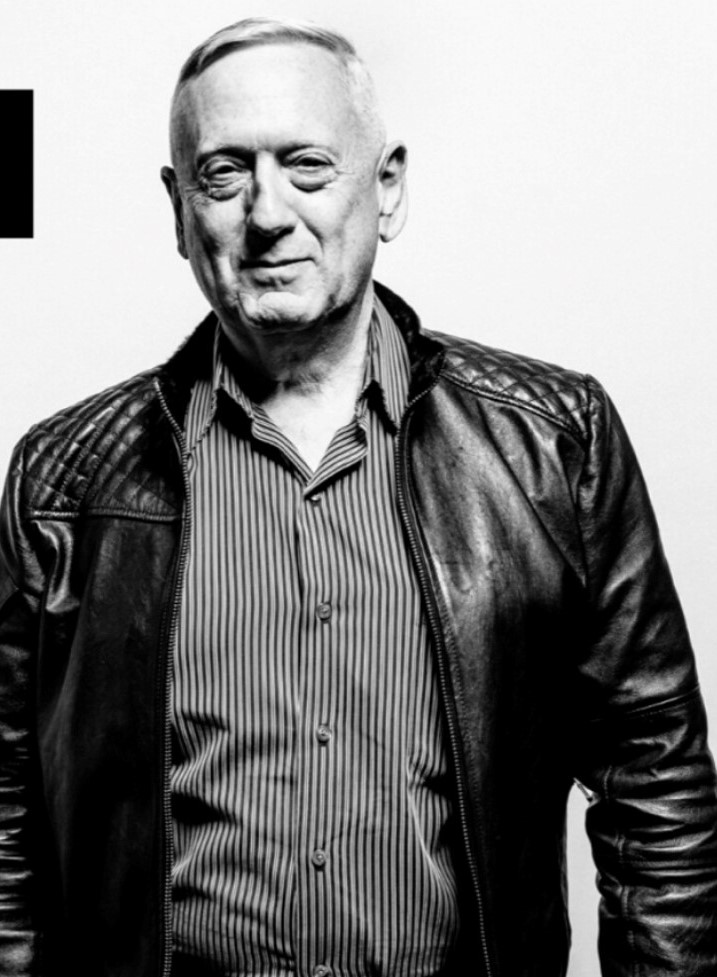

W.J. Astore

Of “Legal” Drug Ads and Anti-Russia Messaging

Mobsters are known for breaking kneecaps to bend people to their will. Marketers break into heads with repetitive and manipulative advertising, images, and narratives. Mobsters of the mind, they are.

I thought of this after watching all those repetitive (and largely interchangeable) ads for “legal” prescription drugs. Rarely do they show the often serious conditions they allegedly treat. Instead it’s image after image of people enjoying life, whether at amusement parks, the beach, dancing, or what-have-you. It’s as if drug companies are selling happiness pills whose only side effect is experiencing the best day of your life. Meanwhile, as images spill into your head of eternal bliss, a narrator quietly intones about potential serious side effects, even possible death in the case of one drug I’ve seen advertised.

Drug ads are the worst. People wonder why Americans take so many illegal drugs and why we have so many drug addictions — well, just look at all the ads for legal drugs, and how they’re advertised as making people incandescently happy. It’s all about the messaging: the repetition of powerful feel-good imagery, with drugs as panaceas.

Speaking of repetition, something similar is true of political manipulation. To cite one example: Russia. Has there ever been a worse “drug” with more serious side effects than Russia? Russia keeps hacking our elections! Russia is led by war criminals! Russia is raping Ukraine! Over and over again, the mainstream media encourages us to hate Russia and Vladimir Putin. Is this truly all we need to know about Russia? As Sting sang, don’t the Russians love their children too? (Back in the 1980s, the media didn’t go easy on Sting for his alleged naïveté and pro-Russian sentiments.)

Whether it’s drug advertisers, the mainstream media, or the U.S. government for that matter, America is infested with various “ministries of truth” that are driven by a mobster-like mentality. They may not break your kneecaps, but they nevertheless find ways to break into your mind.

Now you’ll excuse me while I pop a few pills while denouncing Russia. And China too, perhaps?