W.J. Astore

It didn’t take long, did it? The Taliban are already in Kabul and the American-supported central government has scattered to the winds. What happened? What can we learn from this dramatic collapse?

Images of Saigon in 1975 keep appearing in minds and on TV screens, but let’s not forget the collapse of the American-trained Iraqi military in 2014. It turns out that a special product of America’s military-industrial-Congressional complex is junk militaries, whether in Vietnam in 1975 or Iraq in 2014 or Afghanistan in 2021. As I wrote about in 2014 at TomDispatch.com, the U.S. really knows how to invest in junk armies. And when they inevitably collapse, no one is held responsible, whether in the military or in Congress or in the various mercenary corporations that ostensibly trained and equipped Afghan security forces.

What follows is an excerpt from my article written in 2014 when Iraqi forces collapsed. The lessons I drew from that collapse are applicable to the latest one in Afghanistan. Just substitute “The Taliban” for ISIS and Afghan security forces for Iraqi ones in the paragraphs below.

A Kleptocratic State Produces a Kleptocratic Military

In the military, it’s called an “after action report” or a “hotwash” — a review, that is, of what went wrong and what can be learned, so the same mistakes are not repeated. When it comes to America’s Iraq training mission, four lessons should top any “hotwash” list:

1. Military training, no matter how intensive, and weaponry, no matter how sophisticated and powerful, is no substitute for belief in a cause. Such belief nurtures cohesion and feeds fighting spirit. ISIS has fought with conviction. The expensively trained and equipped Iraqi army hasn’t. The latter lacks a compelling cause held in common. This is not to suggest that ISIS has a cause that’s pure or just. Indeed, it appears to be a complex mélange of religious fundamentalism, sectarian revenge, political ambition, and old-fashioned opportunism (including loot, plain and simple). But so far the combination has proven compelling to its fighters, while Iraq’s security forces appear centered on little more than self-preservation.

2. Military training alone cannot produce loyalty to a dysfunctional and disunified government incapable of running the country effectively, which is a reasonable description of Iraq’s sectarian Shia government. So it should be no surprise that, as Andrew Bacevich has noted, its security forces won’t obey orders. Unlike Tennyson’s six hundred, the Iraqi army is unready to ride into any valley of death on orders from Baghdad. Of course, this problem might be solved through the formation of an Iraqi government that fairly represented all major parties in Iraqi society, not just the Shia majority. But that seems an unlikely possibility at this point. In the meantime, one solution the situation doesn’t call for is more U.S. airpower, weapons, advisers, and training. That’s already been tried — and it failed.

3. A corrupt and kleptocratic government produces a corrupt and kleptocratic army. On Transparency International’s 2013 corruption perceptions index, Iraq came in 171 among the 177 countries surveyed. And that rot can’t be overcome by American “can-do” military training, then or now. In fact, Iraqi security forces mirror the kleptocracy they serve, often existing largely on paper. For example, prior to the June ISIS offensive, as Patrick Cockburn has noted, the security forces in and around Mosul had a paper strength of 60,000, but only an estimated 20,000 of them were actually available for battle. As Cockburn writes, “A common source of additional income for officers is for soldiers to kickback half their salaries to their officers in return for staying at home or doing another job.”

When he asked a recently retired general why the country’s military pancaked in June, Cockburn got this answer:

“‘Corruption! Corruption! Corruption!’ [the general] replied: pervasive corruption had turned the [Iraqi] army into a racket and an investment opportunity in which every officer had to pay for his post. He said the opportunity to make big money in the Iraqi army goes back to the U.S. advisers who set it up ten years ago. The Americans insisted that food and other supplies should be outsourced to private businesses: this meant immense opportunities for graft. A battalion might have a nominal strength of six hundred men and its commanding officer would receive money from the budget to pay for their food, but in fact there were only two hundred men in the barracks so he could pocket the difference. In some cases there were ‘ghost battalions’ that didn’t exist at all but were being paid for just the same.”

Only in fantasies like J.R.R. Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings do ghost battalions make a difference on the battlefield. Systemic graft and rampant corruption can be papered over in parliament, but not when bullets fly and blood flows, as events in June proved.

Such corruption is hardly new (or news). Back in 2005, in his article “Why Iraq Has No Army,” James Fallows noted that Iraqi weapons contracts valued at $1.3 billion shed $500 million for “payoffs, kickbacks, and fraud.” In the same year, Eliot Weinberger, writing in the London Review of Books, cited Sabah Hadum, spokesman for the Iraqi Ministry of the Interior, as admitting, “We are paying about 135,000 [troop salaries], but that does not necessarily mean that 135,000 are actually working.” Already Weinberger saw evidence of up to 50,000 “ghost soldiers” or “invented names whose pay is collected by [Iraqi] officers or bureaucrats.” U.S. government hype to the contrary, little changed between initial training efforts in 2005 and the present day, as Kelley Vlahos noted recently in her article “The Iraqi Army Never Was.”

4. American ignorance of Iraqi culture and a widespread contempt for Iraqis compromised training results. Such ignorance was reflected in the commonplace use by U.S. troops of the term “hajji,” an honorific reserved for those who have made the journey (or hajj) to Mecca, for any Iraqi male; contempt in the use of terms such as “raghead,” in indiscriminate firing and overly aggressive behavior, and most notoriously in the events at Abu Ghraib prison. As Douglas Macgregor, a retired Army colonel, noted in December 2004, American generals and politicians “did not think through the consequences of compelling American soldiers with no knowledge of Arabic or Arab culture to implement intrusive measures inside an Islamic society. We arrested people in front of their families, dragging them away in handcuffs with bags over their heads, and then provided no information to the families of those we incarcerated. In the end, our soldiers killed, maimed, and incarcerated thousands of Arabs, 90 percent of whom were not the enemy. But they are now.”

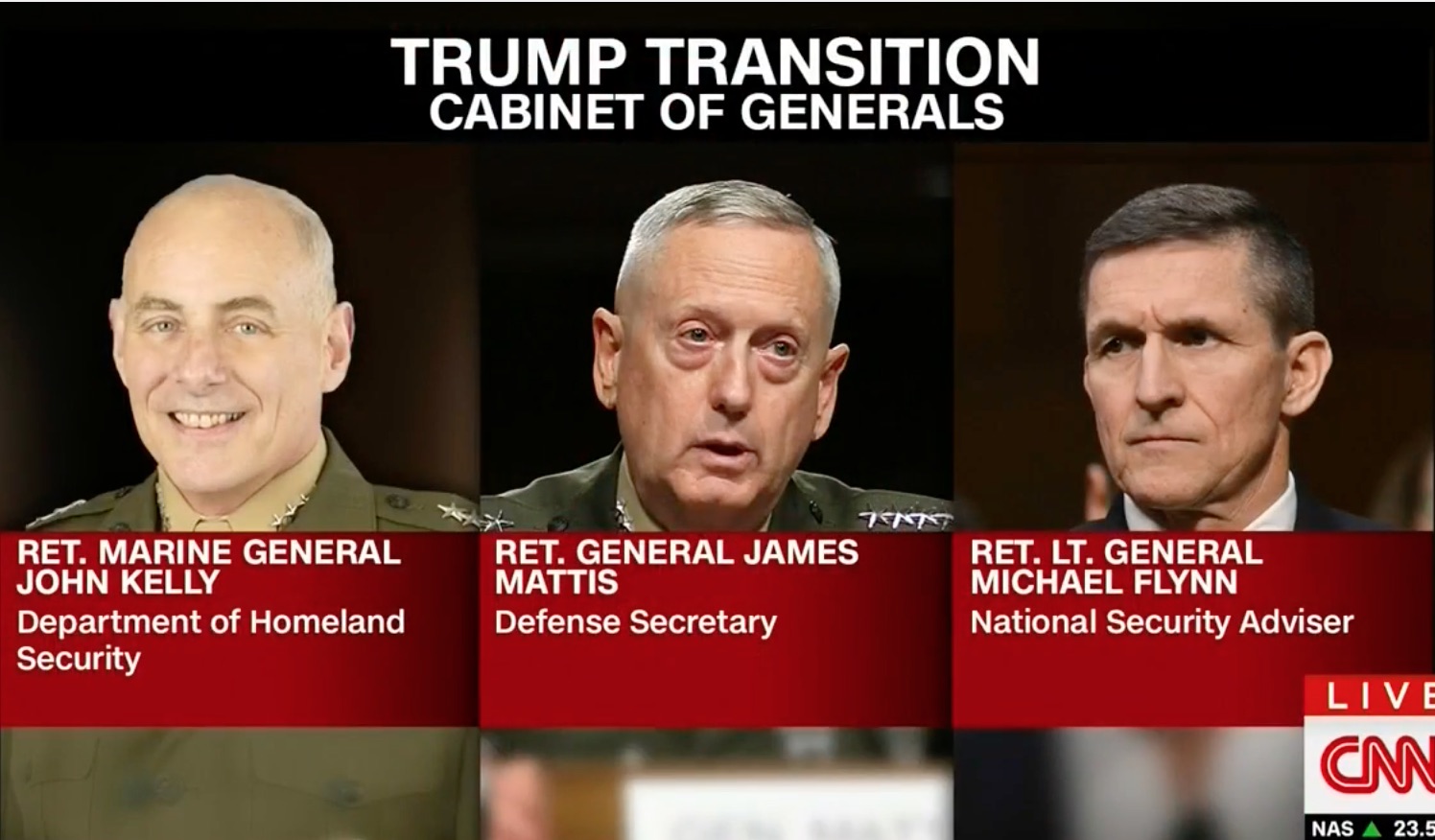

Sharing that contempt was Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld, who chose a metaphor of parent and child, teacher and neophyte, to describe the “progress” of the occupation. He spoke condescendingly of the need to take the “training wheels” off the Iraqi bike of state and let Iraqis pedal for themselves. A decade later, General Allen exhibited a similarly paternalistic attitude in an article he wrote calling for the destruction of the Islamic State. For him, the people of Iraq are “poor benighted” souls, who can nonetheless serve American power adequately as “boots on the ground.” In translation that means they can soak up bullets and become casualties, while the U.S. provides advice and air support. In the general’s vision — which had déjà vu all over again scrawled across it — U.S. advisers were to “orchestrate” future attacks on IS, while Iraq’s security forces learned how to obediently follow their American conductors.

The commonplace mixture of smugness and paternalism Allen revealed hardly bodes well for future operations against the Islamic State.

What Next?

The grim wisdom of Private Hudson in the movie Aliens comes to mind: “Let’s just bug out and call it ‘even,’ OK? What are we talking about this for?”

Unfortunately, no one in the Obama administration is entertaining such sentiments at the moment, despite the fact that ISIS does not actually represent a clear and present danger to the “homeland.” The bugging-out option has, in fact, been tested and proven in Vietnam. After 1973, the U.S. finally walked away from its disastrous war there and, in 1975, South Vietnam fell to the enemy. It was messy and represented a genuine defeat — but no less so than if the U.S. military had intervened yet again in 1975 to “save” its South Vietnamese allies with more weaponry, money, troops, and carpet bombing. Since then, the Vietnamese have somehow managed to chart their own course without any of the above and almost 40 years later, the U.S. and Vietnam find themselves informally allied against China.

To many Americans, IS appears to be the latest Islamic version of the old communist threat — a bad crew who must be hunted down and destroyed. This, of course, is something the U.S. tried in the region first against Saddam Hussein in 1991 and again in 2003, then against various Sunni and Shiite insurgencies, and now against the Islamic State. Given the paradigm — a threat to our way of life — pulling out is never an option, even though it would remove the “American Satan” card from the IS propaganda deck. To pull out means to leave behind much bloodshed and many grim acts. Harsh, I know, but is it any harsher than incessant American-led bombing, the commitment of more American “advisers” and money and weapons, and yet more American generals posturing as the conductors of Iraqi affairs? With, of course, the usual results.

One thing is clear: the foreign armies that the U.S. invests so much money, time, and effort in training and equipping don’t act as if America’s enemies are their enemies. Contrary to the behavior predicted by Donald Rumsfeld, when the U.S. removes those “training wheels” from its client militaries, they pedal furiously (when they pedal at all) in directions wholly unexpected by, and often undesirable to, their American paymasters.

And if that’s not a clear sign of the failure of U.S. foreign policy, I don’t know what is.