An Old Paper from 1993

JAN 29, 2026

Scrolling through old files today, I came across this paper that I prepared for a “Strategic Studies Seminar” at Oxford that I presented on 28 January 1993. Back then, I was a captain in the Air Force, and in the room were other serving and retired military officers. Anyhow, here’s what I read to my peers (and the two professors hosting the seminar) about the U.S. defeat in Vietnam. Again, this presentation is 33 years old, but I hope it’s still useful despite its age.

Insurgencies and America’s Defeat in Vietnam (1993)

A revolutionary war is a war within a state; the ultimate aim of the insurgents is political control of the state. Nowhere is Clausewitz’s dictum of war as a continuation of politics more true than in a revolutionary war. It typically takes the form of a protracted struggle, conducted patiently and inexorably, a variant of Chinese water torture. Educating or, more accurately, indoctrinating, the people – gaining their sympathy, cooperation, and assistance – is paramount. And all people have a role to play: men and women, young and old. After World War II, insurgencies have been guided by Mao Zedong’s concept of People’s War, and inspired by a complex combination of nationalism, anti-colonialism, and communism. They have bedeviled France, Great Britain, and the United States. This paper addresses the strategy of People’s War in terms of means, ends, and will, and details some of the reasons why the United States lost the Vietnam War.

The strategic end of People’s War is simple in its boldness: the overthrow of the existing government and its replacement with an insurgent-led government. The means are incredibly complex, encompassing social, economic, psychological, military, and political dimensions, but it must be remembered that all means are directed towards the political end. Strength of will usually favors the insurgents, partly because a major goal of People’s War is to mold the minds of its followers to convince them of the righteousness of their cause.

People’s War passes through three stages. At first the insurgents get to know the people as they spread propaganda and build a political infrastructure.

Every insurgent is an ambassador for the cause. They create safe havens while intimidating opponents and neutrals, and they commit terrorist acts to undermine the legitimacy of the government. They build their safe havens on the periphery of the state, usually in rural or impoverished areas where they can feed on the misery of the people. The more difficult the terrain, the better, whether it be the mountains of Spain and Afghanistan or the jungles of Malaya and Vietnam. They extend their control over the countryside and into the urban areas during the second stage of People’s War. They use guerrilla tactics and terrorism to further undermine the political legitimacy of the government. The main target is not the government’s troops but the will of its leaders. As they extend their physical control over the countryside, they install their own political structure to control the people. With the government’s will fatally weakened, the insurgents move to the final stage: a conventional military offensive to overthrow the government.

The three stages are not rigidly sequential, however. For example, while conducting guerrilla operations against the government, the insurgents continue to build their infrastructure, conduct terrorist acts, and spread propaganda. Even during the last stage — the general offensive — the insurgents continue stages one and two. This aspect of People’s War was well expressed by John M. Gates in the Journal of Military History in July 1990:

American conventional war doctrine does not anticipate reliance upon population within the enemy’s territory for logistical and combat support. It does not rely upon guerrilla units to fix the enemy, establish clear lines of communication, and maintain security in the rear. And it certainly does not expect enemy morale to be undermined by political cadres within the very heart of the enemy’s territory, cadres who will assume positions of political power as the offensive progresses. Yet all of these things happened in South Vietnam in 1975….

Flexibility, judgement, and comprehensiveness of methods are the keys to success. If the insurgents overestimate the weakness of the government and lose large-scale battles, they slip back into the earlier two phases and continue to work towards weakening the government for the next general offensive.

It bears repeating the primary goal of insurgents is political control. Military actions are only one tool for obtaining this control. As Mao cautions, guerrilla operations are just “one aspect of the revolutionary struggle.” The insurgent appeals to the hearts and minds of the people. He is, after all, one of them. Too much can be made of Mao’s “fish and sea” analogy. The insurgent is not just a fish that swims in the sea of the people: his purpose is to convert the sea to his purpose. He wants to walk on water. He employs any method to command the sea to his will. He would prefer ideological converts, true believers, but converts through terror are acceptable. Those who can’t be converted he ruthlessly kills. That his methods produce squeamishness among some in the West only accentuates their value to him.

As a strategy, People’s War is difficult but not impossible to counter. The United States defeated the Philippine insurrection in the first two decades of this century, and after World War II Great Britain put down a communist insurgency in Malaya. More famous, however, have been the stunning successes of People’s War: Mao’s victory over Japan and the Nationalists in the 1930s and ‘40s, and Ho Chi Minh’s victories over France and the United States in the 1950s, ‘60s, and ‘70s. Perhaps most unsettling was America’s defeat in Vietnam. How could the world’s foremost superpower lose to, in the words of General Richard G. Stilwell in 1980, a “fourth-rate half-country?”

There are no simple answers to America’s defeat, although Hollywood tells us otherwise. A theory still believed by some in the US military is a variation of the German “stab-in-the-back” legend of the Great War. Our hands were tied by meddling civilians who didn’t let the military fight and win the war. One American soldier is the equal of hundreds of pajama-clad midgets, or so it appears in the Rambo flicks. A wretched, dishonorable government also abandoned our POWs to the godless communists, now rescued several times over by Stallone, Chuck Norris, and other martial arts experts. That such films make money is an affront to the genuine sacrifices of Americans represented so tragically by the Vietnam War memorial in Washington.

Perhaps such sentiments seem out of place in a paper devoted to a dispassionate strategic analysis of America’s role in Vietnam. Yet my feelings are perhaps typical of the emotionalism that still surrounds this topic among Americans. A dispassionate critique from an American, let alone an American service member, may still be impossible; nevertheless, I’ll give it a shot.

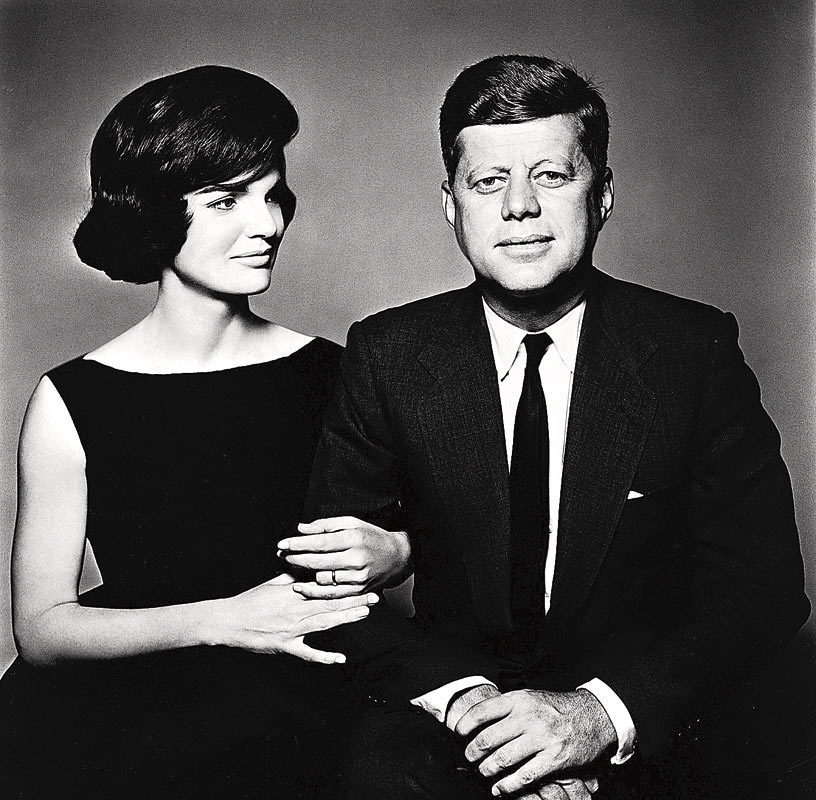

The United States lost the war for several related reasons. First, we fought the wrong kind of war. As the Navy and especially the Air Force built up their nuclear forces, the army chaffed against its “New Look” and diminished role in the 1950s. Under Kennedy and Johnson, the Army had a new doctrine – Flexible Response – and an opportunity – the Vietnam War – to prove its worth. Vietnam was to be the proving ground for a revitalized Army.

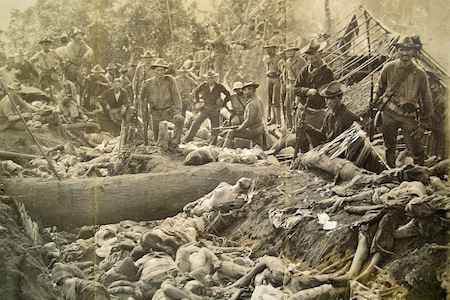

The opposite proved to be the case because the Army pursued the wrong strategy. From 1965-68, when we sent more than half a million troops to Vietnam, the US Army tried to fight a conventional war against the Viet Cong (VC) and North Vietnamese Army (NVA). As LTG Harry Kinnard, commander of the Army’s elite 1st Cavalry Division (Airmobile), put it, “I wanted to make them fight our kind of war. I wanted to turn it into a conventional war – boundaries – and here we go, and what are you going to do to stop us?” Obeying Mao’s teachings, the VC and NVA wisely avoided stand up fights. The Army responded with search-and-destroy operations to find, fix and kill the enemy. The goal was attrition through decisive battles, reflected by high body counts. Nothing illustrates the bankruptcy of American strategy better than the idea of body counts. In theory, a high body count means you’re killing the fish in the sea, without hurting the sea. In practice, a high body count is a measure of the success of the insurgents: they’re recruiting many fish to their cause. And in killing the fish, Americans poisoned the sea with defoliants, bomb craters, unexploded artillery shells, the list goes on. Americans were stuck in Catch-22 dilemmas: they had to destroy villages to save them, they had to destroy villagers’ crops while pursuing guerrilla bands. Such an approach flies in the face of Mao’s “Three Rules and Eight Remarks,” which exhibit a profound respect for the people and their property.

After killing, or perhaps more often not killing, the guerrillas, the Army left, and the guerrillas regained control of the area. This did not disturb LTG Stanley Larson, who observed that if guerrillas returned, “we’ll go back in and kill more of the sons of bitches.” But the VC and NVA retained the initiative, had plenty of manpower, and time was on their side.

Why did the Army pursue such a faulty strategy? In part due to the legacy of World War II, particularly American experience in the Pacific. In island-hopping to Japan, Americans gained faith in massive firepower and lost interest in controlling land. The islands were a means to an end, not the end itself, and success could be measured in some sense by the number of Japanese casualties. Such was not the case in Vietnam, where control of the land was essential to winning the support of the people. Part of the Army’s problem was its lack of experience in counterinsurgency (or COIN) operations. Ronald Spector reports that in the 1950s, COIN operations were limited to four hours in most infantry training courses. What little was taught focused on preventing a conventional enemy from holding raids or infiltrating rear areas. But in the end, the Army fought the war it was trained to fight: a conventional war of maneuver and massive firepower. This worked well in Desert Storm, but failed in Vietnam.

In contrast to the Army, the Marines were far more aware of the nature of the war they were fighting, reports Andrew Krepinevich. They combined 15 marines and 34 Popular Force territorial troops (who lived in and provided security for a village or hamlet) into combat action platoons (CAPs). These CAPs sought to destroy insurgent infrastructure, protect the people and the government infrastructure, organize local intelligence networks, and train local paramilitary troops. In other words, they adopted traditional COIN tactics. But the Army ran the show in Vietnam, and its leaders rejected the Marines’ approach.

The Marines were not alone in their appreciation of the multidimensional aspects of COIN. Robert Komer’s Phoenix program also targeted the Viet Cong infrastructure, but the efforts of the CIA were not well coordinated with those of the military or the State Department, let alone the South Vietnamese. In fact Westmoreland refused to create a combined command to coordinate American actions with those of the South Vietnamese. The latter were an especially neglected resource. Admittedly, the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) was corrupt and at times incompetent, but part of the problem was caused by American mistraining and the Army’s contempt. In the 1950s, American military advisors trained ARVN to repel a conventional invasion from the north, using North Korea as a model. From 1965-68, the US Army gave ARVN the static security mission, judged to be of low importance by the Army. US advisors assigned to help ARVN recognized their careers were endangered: they would advance far quicker if they had “true” combat assignments. After years of neglect, ARVN was built up with billions of US dollars during Nixon’s Vietnamization policy (and that’s exactly what it was – a policy, not a strategy), but by 1969 the rot had gone too far. ARVN lacked a unifying national spirit, VC agents had penetrated the ranks, and the officers were thoroughly politicized. Our ally always thought we’d be there if they ran into trouble, but they didn’t understand how American government worked. As Ambassador Bui Diem explained in 1990, “Our faith in America was total, and our ignorance was equally total.” South Vietnam paid the price in 1975.

Could the United States have won the Vietnam War if we had followed a proper strategy? This question may be unanswerable and ultimately moot, but it’s worth discussing. First, one must admit the war may not have been worth winning. Hannah Arendt has stated the Vietnam War was a case of excess means applied for minor aims in a region of marginal interest. In retrospect this seems irrefutable, but in the climate of the Cold War and Containment Vietnam seemed a critical theater in which communist aggression had to be stopped. Second, one must admit the United States was not protecting a viable government in South Vietnam: we were trying to create one. But we were creating one in our image. We ignored the Vietnamese culture and destroyed their economy with our hard currency. Rear area troops with money to spend spread prostitution and drugs in the streets of Saigon. In short, we alienated the people instead of winning them over to our cause. The few people we did win over were terrorized and often killed by the Viet Cong. Even following a proper COIN strategy, victory would have taken 5-10 more years at least. With weak support from the American people, (the “Silent Majority” was silent due to its ignorance and ambivalence), which waned dramatically after Tet, we never had a chance in Vietnam.

The one strategy that would have succeeded for the United States, I believe, is Mao’s People’s War. We must not deceive ourselves: if free elections had been held as promised in 1956, Ho Chi Minh would have won and unified the country. His was the legitimate government; we were trying to overthrow that government and replace it with almost any non-communist regime. In that effort, we should have formed an alliance of military, state department, intelligence, and academic resources to educate Americans in Vietnamese language and culture. These experts, with a suitable, politically-indoctrinated military force to protect them, would win the hearts of the people. Our main weapons would be our ideas and the ideological fervor of our troops, whether civilian or military. Diplomacy and military strikes would be used to cut-off the flow of arms to the VC and NVA from the Soviet Union. The political infrastructure of the enemy would be targeted, including Ho Chi Minh himself.

But this is ridiculous. Our very arrogance blinded us to the war’s complexities. We attacked the symptoms of the disease – the guerrillas and NVA – without examining what caused the disease in the body politic. Our can-do attitude was reinforced by our military traditions and our pride in our nation as being more moral than the rest of the world. We became our own worst enemy as we tried to manage the war. The commitment was there (at least among the soldiers), the energy was there, the money was there, the technology was there -the strategy, intelligence, and leadership wasn’t. People’s War proved superior to search-and-destroy, the VC and NVA intelligence proved superior to ARVN and ignorant Americans, the brilliant Giap out-thought the dedicated but shortsighted Westmoreland. The Vietnam War was ultimately unwinnable.

In the aftermath of the American-led victory over Iraq in Desert Storm, many Americans predicted the stigma of our defeat in Vietnam had finally been exorcised from our minds. Such was not the case, nor is such a result even desirable. The “dreaded V-word,” as the London Times recently described it, is being whispered again in the endless corridors of the Pentagon. If this breeds an aversion to the use of military force, harm may result; but if it leads to more thought and a more subtle study of the efficacy of military force as applied under different conditions, the dreaded V-word will have served a useful purpose, and those names engraved on the Wall in Washington will not have died in vain.