W.J. Astore

My wife and I were talking about the Republican attack on Planned Parenthood and how ludicrous it is in the grand scheme of things. The Federal Government contributes just over $500 million to the budget of Planned Parenthood. That’s the equivalent of two F-35 jet fighters to support vitally important health services provided at 700 clinics across the country. Talk about bang for the buck!

If a person playing with a full deck had to make a choice, which would she choose to fund: basic medical and information services for nearly three million Americans each year, or two underperforming F-35 jet fighters? Indeed, for the projected cost of the F-35 program, you could easily fund Planned Parenthood for more than 2000 years!

Speaking of Planned Parenthood, it’s reassuring to know such centers and clinics exist, especially given how squeamish Americans are, generally speaking, about sex. Planned Parenthood provides invaluable services at low cost, but I guess Congress prefers funding extraneous jet fighters at sky-high cost.

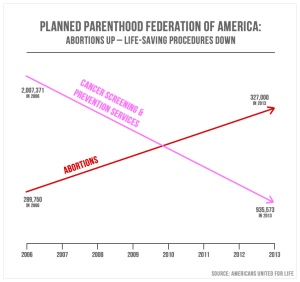

The true chart for the services rendered by Planned Parenthood is below, courtesy of Politifact. The false chart had been used to suggest Planned Parenthood was increasing abortions and decreasing cancer screening services. But a decline in cancer screening is due mainly to changes in frequency of pap smears, and abortion rates have held steady across time. Note all of the other services provided, to include screening for STDs.

<

Of course, phony charts and Congressional hearings are all about politics and hot button issues like abortion. Hysterical opposition to Planned Parenthood is a cynical exercise in emotional manipulation by disinformation and scare-mongering. The sad thing is how easily it gains traction in our country.

Even as Republican men (yes — it’s mostly men) beat their collective chests about Planned Parenthood, consider that the Federal Budget (discretionary) for FY 2016 is $1.168 trillion. Recall that total federal funding for Planned Parenthood is a mere $500 million. If this was shown on a pie chart, the budgetary piece for Planned Parenthood would not be a slice; not even a sliver. It would be a flake off of the crust.

Compare this to defense spending, Homeland Security, and war funding, which constitutes more than half the federal pie (discretionary spending), and which a Republican Congress wants to increase. Still think we should focus on flakes off the crust of the pie?

For shame, Congress. For shame, all of us, for allowing our politics to be manipulated by liars, opportunists, and ignoramuses.

(Note: Planned Parenthood “provides sexual and reproductive health care, education, information, and outreach to more than five million women, men, and adolescents worldwide each year. 2.7 million women and men in the United States annually visit Planned Parenthood affiliate health centers for trusted health care services and information.” Well, they would say that, wouldn’t they? Except that it’s true.)