W.J. Astore

The blurring and blending of sports and war

I never miss a Super Bowl, and this year’s game was close until its somewhat anti-climatic end. Of course, there’s always a winning team and a losing one, but perhaps the biggest winner remains the military-industrial complex, which is always featured and saluted in these games.

How so? The obligatory military flyover featured Navy jets flown by female pilots. Progress! The obligatory shot of an overseas (or on-the-sea) military unit featured the colorful crew of the USS Carl Vinson, an aircraft carrier. A Marine Corps color guard marched out the American flag along with the flags of each of the armed services. The announcers made a point to “honor those who fight for our nation.” All this is standard stuff, a repetitive ritual that turns the Super Bowl into Veterans Day, if only for a few minutes.

What was new about this year’s ceremony was the celebration of Pat Tillman’s life, the sole NFL player (and I think the only athlete in any of America’s “major” sports leagues) to give up his career and hefty paycheck to enlist in the U.S. military after 9/11. Yes, Pat Tillman deserves praise for that, and since the game was played in Arizona and Tillman had been with the Arizona Cardinals, honoring him was understandable. Yet, the network (in this case, Fox) quickly said he’d “lost his life in the line of duty.” No further details.

Tillman was killed in a friendly-fire incident that was covered up by the U.S. military in a conspiracy that went at least as high as Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld. The military told the Tillman family Pat had died heroically in combat with the enemy in Afghanistan and awarded him the Silver Star. The Tillman family eventually learned the truth, that Pat had been killed by accident in the chaos of war, a casualty of FUBAR, because troops in combat, hyped on adrenaline, confused and under stress, make deadly mistakes far more often than we’d like to admit.

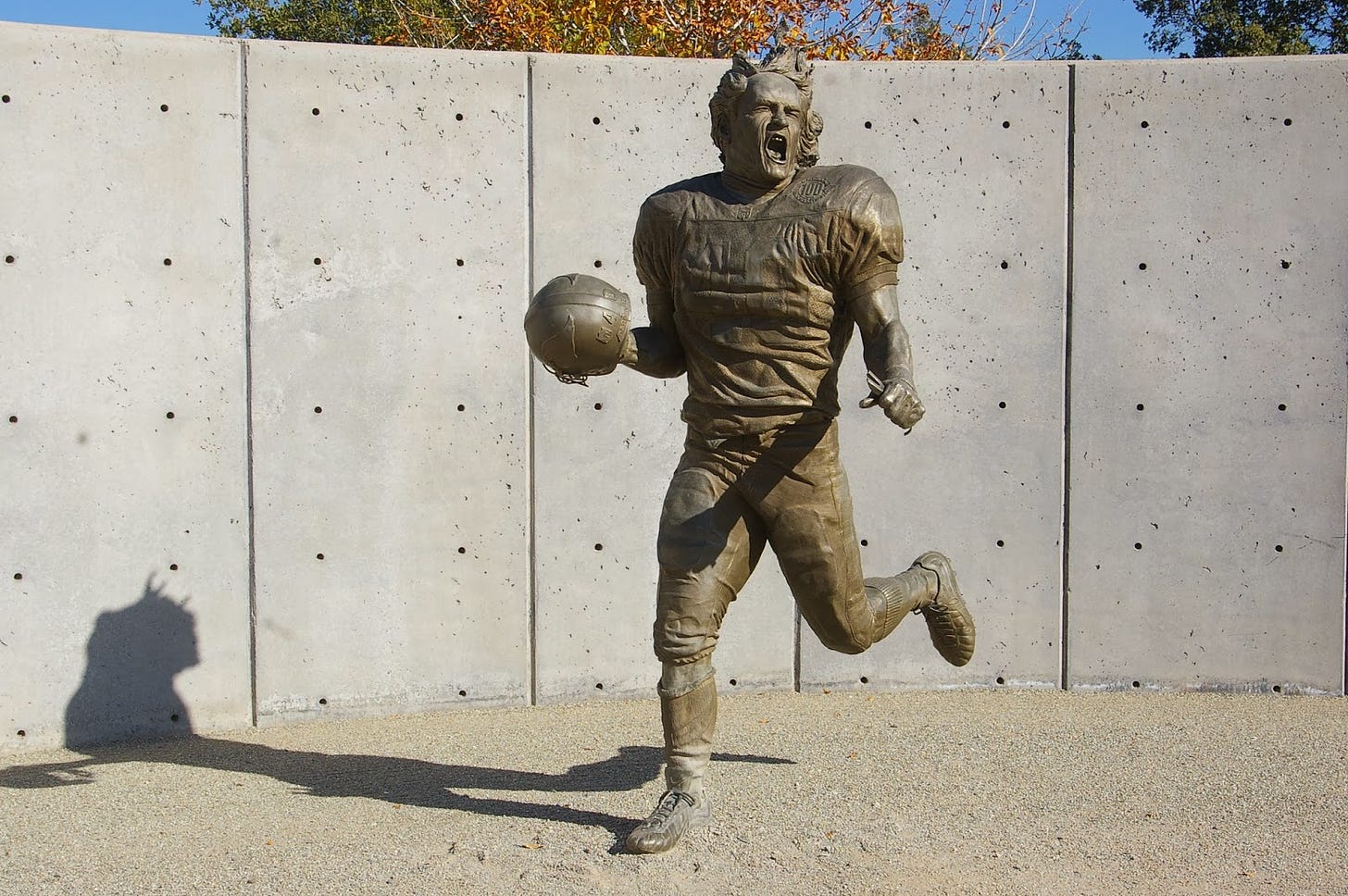

What makes me sad more than angry is how Tillman’s legacy is being used to sell the military as a good and noble place, a path toward self-actualization. Tillman, a thoughtful person, a soldier who questioned the war he was in, is now being reduced to a simple heroic archetype, just another recruitment statue for the U.S. military.

His life was more meaningful than that. His lesson more profound. His was a cautionary tale of a life of service and sacrifice in a war gone wrong; his death and the military’s lies about the same are grim lessons about the waste of war, its lack of nobility, the sheer awfulness of it all.

Tillman’s statue captures the essence of a man full of life. His death by friendly fire in a misbegotten war, made worse by the lies told to the Tillman family by the U.S. military, reminds us that the essence of war is death.

That was obviously not the intended message of this Super Bowl tribute. That message was of military service as transformative, as full of grace, and I’m sorry but I just can’t stomach it because of what happened to Pat Tillman and how he was killed not only by friendly fire on the ground but how his life was then mutilated by those at the highest levels of the U.S. military.