W.J. Astore

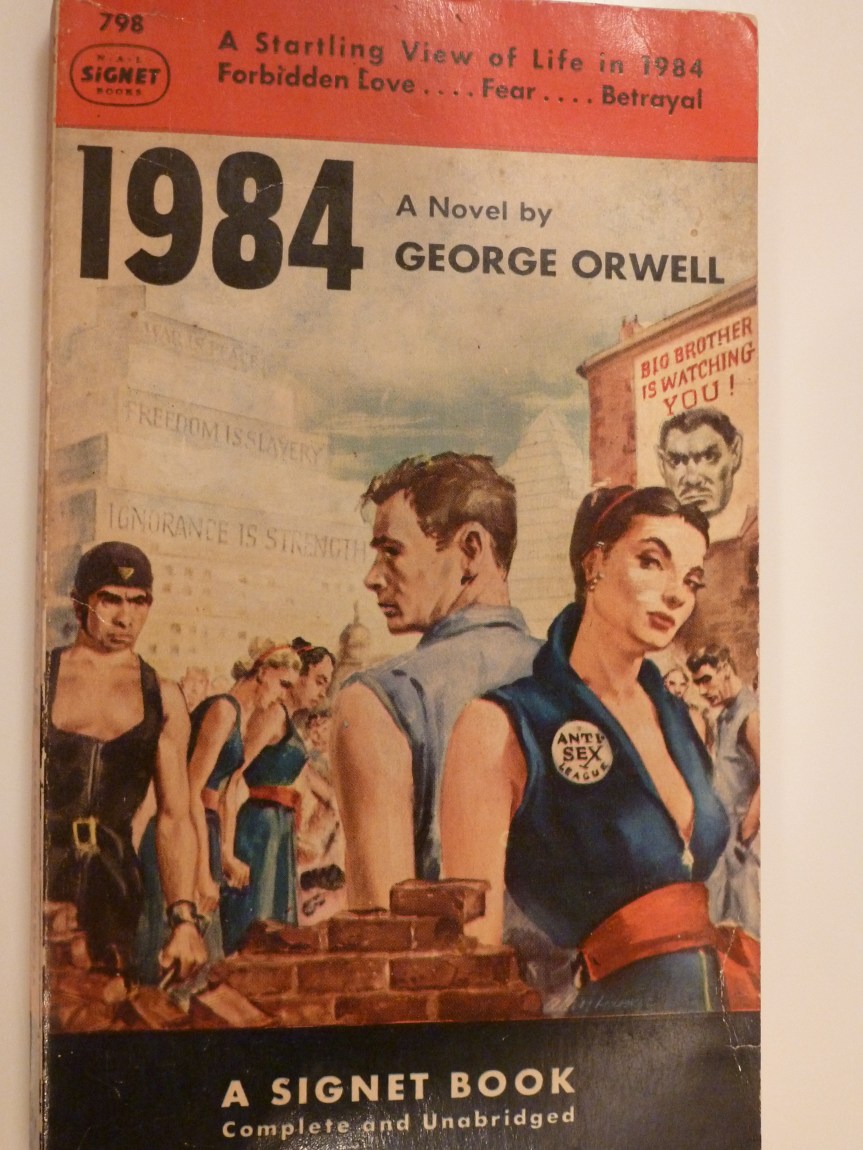

Syme is a minor character in George Orwell’s “1984.” A philologist, Syme works on the Eleventh Edition of the Newspeak dictionary, “the definitive edition” according to him. What’s fascinating is Orwell’s description of the intent and main functions of Newspeak, as given by Syme in this passage:

“You think … our chief job is inventing new words. But not a bit of it! We’re destroying words—scores of them, hundreds of them, every day. We’re cutting language down to the bone … You don’t grasp the beauty of the destruction of words. Do you know that Newspeak is the only language in the world whose vocabulary gets smaller every year?”

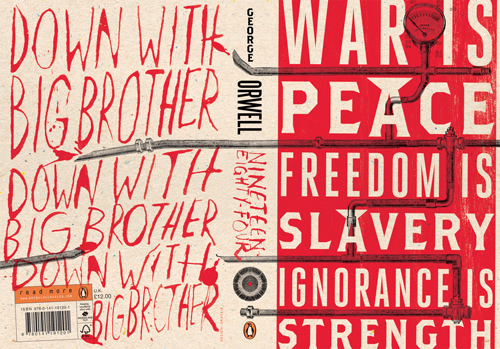

“Don’t you see that the whole aim of Newspeak is to narrow the range of thought? In the end we shall make thought-crime literally impossible, because there will be no words in which to express it. Every concept that can ever be needed will be expressed by exactly one word, with its meaning rigidly defined and all its subsidiary meanings rubbed out and forgotten … Every year fewer and fewer words, and the range of consciousness always a little smaller… The Revolution will be complete when the language is perfect…”

“Even the literature of the Party will change. Even the slogans will change. How could you have a slogan like ‘freedom is slavery’ when the concept of freedom has been abolished? The whole climate of thought will be different. In fact there will be no thought, as we understand it now. Orthodoxy means not thinking—not needing to think. Orthodoxy is unconsciousness.”

This brilliant passage by Orwell sends chills up my spine. There will be no thought. Orthodoxy means not thinking. Is this not in fact true of many people today, content to express unquestioning and unwavering obedience to “the Party,” like the people who support Donald Trump simply because he says he’ll make America great again?

After Syme’s oration on Newspeak, Winston Smith, the main protagonist of “1984,” thinks to himself: “Syme will be vaporized. He is too intelligent. He sees too clearly and speaks too plainly. The Party does not like such people. One day he will disappear. It is written in his face.”

A couple of pages later, Syme makes another penetrating observation:

“There is a word in Newspeak … I don’t know whether you know it: duckspeak, to quack like a duck. It is one of those interesting words that have two contradictory meanings. Applied to an opponent, it is abuse; applied to someone you agree with, it is praise.”

To this observation, Winston thinks to himself: “Unquestionably Syme will be vaporized.”

Why? Orwell notes that Syme is a Party zealot, a true believer. But what he lacks, Orwell makes clear, is unconsciousness. Syme is too self-aware, and speaks too plainly, therefore he must go. And indeed later in the book he does disappear.

(As an aside, I like Orwell’s reference to some of Syme’s fatal flaws: that he “read too many books” and “frequented … [the] haunt of painters and musicians.” Yes: books and the arts are indeed the enemy of unconscious orthodoxy in any state.)

The other day, a reader sent to me the following unattributed saying: We build our houses out of words, then we live in them.

In “1984,” the Party sought total control over language, over words, as a way of dominating people’s consciousness.

One of my favorite sayings of Orwell, also from “1984” and one I always shared with my students, goes something like this: Who controls the past controls the future. Who controls the present controls the past.

I think you could add to that: Who controls the language, the very words with which we communicate and think, controls the present.

Language is the key, a point Orwell brilliantly makes through the character of Syme in “1984.”