With fires raging in California and Oregon, and with unemployment rates high, I recalled the experiences of my dad, which I wrote about twelve years ago for TomDispatch.com. My dad served in the Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC), mainly fighting forest fires in Oregon. The CCC was one of those alphabet soup agencies created by FDR’s administration to put people back to work while paying them a meaningful wage. You might call it “democratic socialism,” but I prefer to call it common sense and applaud its spirit of service to country.

We need to revive national service while deemphasizing its military aspects. There are all sorts of honorable services one can render to one’s fellow citizens, as my father’s example shows from the 1930s, an era that now seems almost biblical in its remoteness from today’s concerns.

How America Was Once Rebuilt

Before surging ahead, however, let’s look back. Seventy-five years ago, our country faced an even deeper depression. Millions of men had neither jobs, nor job prospects. Families were struggling to put food on the table. And President Franklin Delano Roosevelt acted. He created the Civilian Conservation Corps, soon widely known as the CCC.

From 1933 to 1942, the CCC enrolled nearly 3.5 million men in roughly 4,500 camps across the country. It helped to build roads, build and repair bridges, clear brush and fight forest fires, create state parks and recreational areas, and otherwise develop and improve our nation’s infrastructure — work no less desperately needed today than it was back then. These young men — women were not included — willingly lived in primitive camps and barracks, sacrificing to support their families who were hurting back home.

My father, who served in the CCC from 1935 to 1937, was among those young men. They earned $30 a month for their labor — a dollar a day — and he sent home $25 of that to support the family. For those modest wages, he and others like him gave liberally to our country in return. The stats are still impressive: 800 state parks developed; 125,000 miles of road built; more than two billion trees planted; 972 million fish stocked. The list goes on and on in jaw-dropping detail.

Not only did the CCC improve our country physically, you might even say that experiencing it prepared a significant part of the “greatest generation” of World War II for greatness. After all, veterans of the CCC had already learned to work and sacrifice for something larger than themselves — for, in fact, their families, their state, their country. As important as the G.I. Bill was to veterans returning from that war and to our country’s economic boom in the 1950s, the CCC was certainly no less important in building character and instilling an ethic of teamwork, service, and sacrifice in a generation of American men.

Today, we desperately need to tap a similar ethic of service to country. The parlous health of our communities, our rickety infrastructure, and our increasingly rickety country demands nothing less.

Of course, I’m hardly alone in suggesting the importance of national service. Last year, in Time Magazine, for example, Richard Stengel called for a revival of national service and urged the formation of a “Green Corps,” analogous to the CCC, and dedicated to the rejuvenation of our national infrastructure.

To mark the seventh anniversary of 9/11, John McCain and Barack Obama recently spoke in glowing terms of national service at a forum hosted by Columbia University. Both men expressed support for increased governmental spending, with McCain promising that, as president, he would sign into law the Kennedy-Hatch “Serve America Act,” which would, among other things, triple the size of the AmeriCorps. (Of course, McCain had just come from a Republican convention that had again and again mocked Obama’s time as a “community organizer” and, even at Columbia, he expressed a preference for faith-based organizations and the private sector over service programs run by the government.) Obama has made national service a pillar of his campaign, promising to spend $3.5 billion annually to more than triple the size of AmeriCorps, while also doubling the size of the Peace Corps.

It all sounds impressive. But is it? Compared to the roughly $900 billion being spent in FY2009 on national defense, homeland security, intelligence, and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, $3.5 billion seems like chump change, not a major investment in national service or in Americans. When you consider the problems facing American workers and our country, both McCain and Obama are remarkable in their timidity. Now is surely not the time to tinker with the controls on a ship of state that’s listing dangerously to starboard.

Do I overstate? Here are just two data points. Last month our national unemployment rate rose to 6.1%, a five-year high. This year alone, we’ve shed more than 600,000 jobs in eight months. If you include the so-called marginally attached jobless, 11 million Americans are currently out of work, which adds up to a real unemployment rate of 7.1%. Now, that doesn’t begin to compare to the unemployment rate during the Great Depression which, at times, exceeded 20%. In absolute terms, however, 11 million unemployed American workers represent an enormous waste of human potential.

How can we get people off the jobless rolls, while offering them useful tasks that will help support families, while building character, community, and country?

Here’s where our federal government really should step in, just as it did in 1933. For we face an enormous national challenge today which goes largely unaddressed: shoring up our nation’s crumbling infrastructure. The prestigious American Society of Civil Engineers did a survey of, and a report card on, the state of the American infrastructure. Our country’s backbone earned a dismal “D,” barely above a failing (and fatal) grade. The Society estimates that we need to invest $1.6 trillion in infrastructure maintenance and improvements over the next five years or face ever more collapsing bridges and bursting dams. It’s a staggering sum, until you realize that we’re already approaching a trillion dollars spent on the Iraq war alone.

No less pressing than a trillion-dollar investment in our nation’s physical health is a commensurate investment in the emotional and civic well-being of our country — not just the drop-in-the-bucket amounts both Obama and McCain are talking about, but something commensurate with the task ahead of us. As our president dithers, even refusing to use the “R” word of recession, The Wall Street Journal quotes Mark Gertler, a New York University economist, simply stating this is “the worst financial crisis since the Great Depression.”

The best and fairest way to head off that crisis is not simply to spend untold scores of billions of taxpayer dollars rescuing (or even liquidating) recklessly speculative outfits that gave no thought to ordinary workers while they were living large. Rather, our government should invest scores of billions in empowering the ordinary American worker, particularly those who have suffered the most from the economic ravages of our financial hurricane.

Just as in 1933, a call today to serve our country and strengthen its infrastructure would serve to reenergize a shared sense of commitment to America. Such service would touch millions of Americans in powerful ways that can’t be fully predicted in advance, just as it touched my father as a young man.

What “Ordinary” Americans Are Capable Of

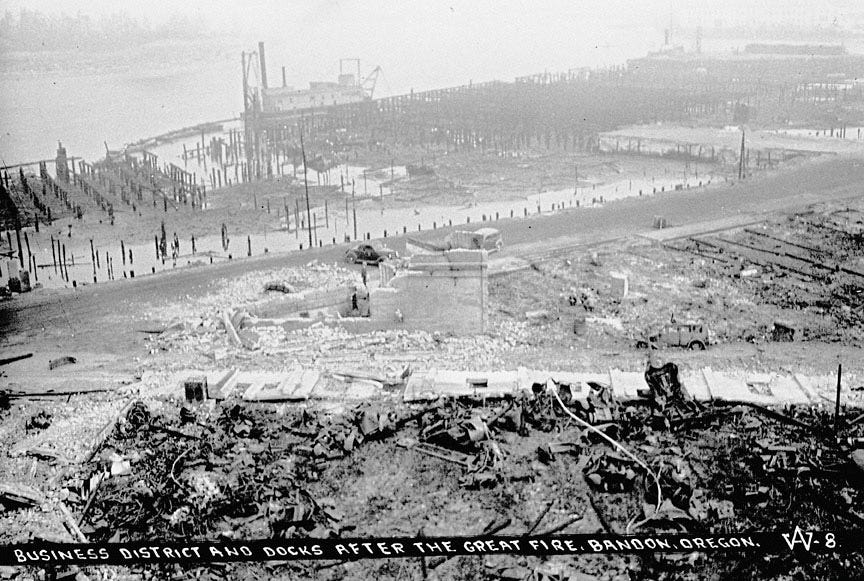

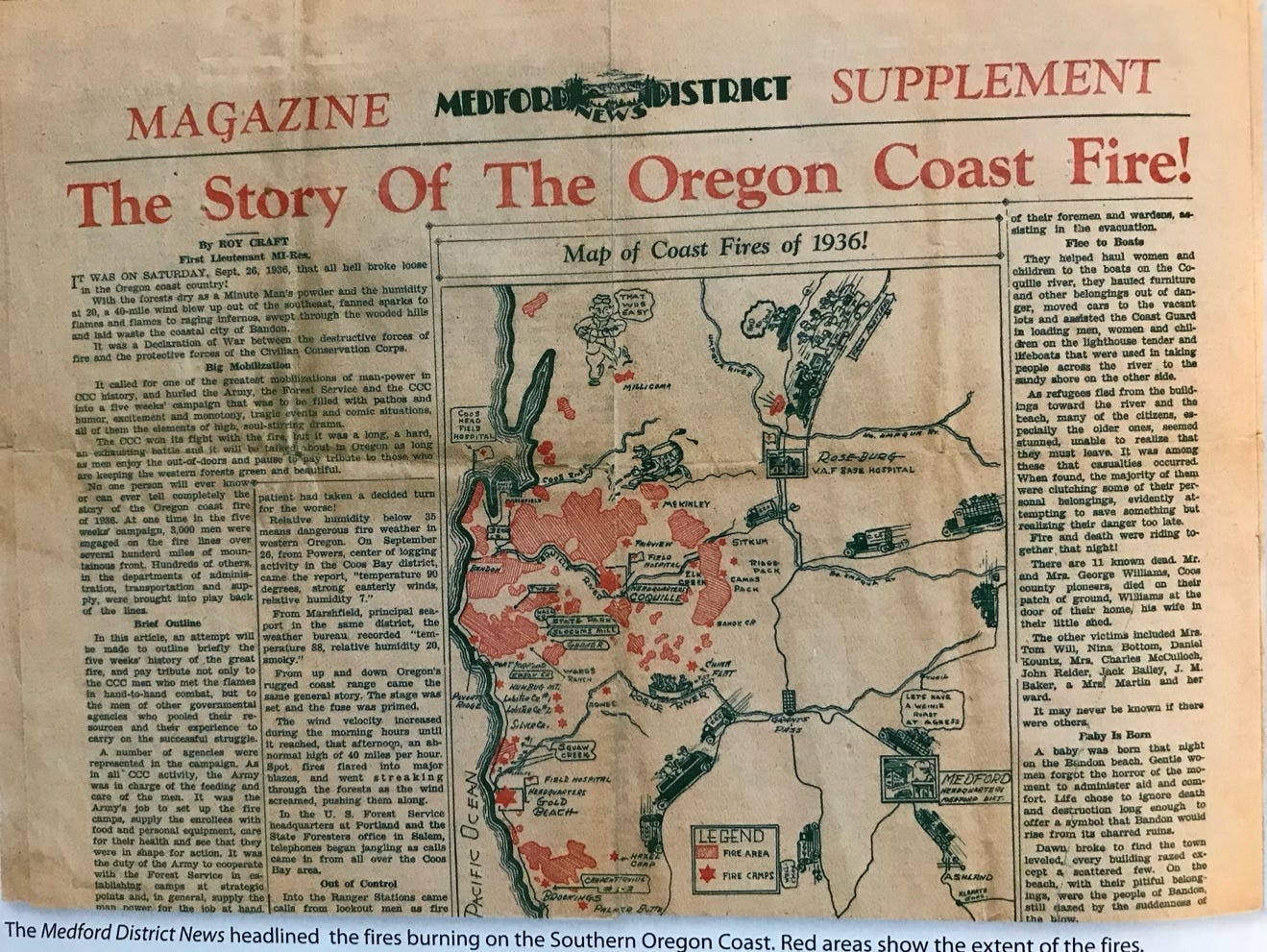

My father was a self-confessed “regular guy,” and his CCC service was typical. He was a “woodsman-falling,” a somewhat droll job title perhaps, but one that concealed considerable danger. In the fall of 1936, he fought the Bandon forest fire in Oregon, a huge conflagration that burned 100,000 acres and killed a dozen people. To corral and contain that fire, he and the other “fellows” in his company worked on the fire lines for five straight weeks. At one point, my father worked 22 hours straight, in part because the fire raged so fiercely and so close to him that he was too scared to sleep (as he admitted to me long after).

My father was 19 when he fought that fire. Previously, he had been a newspaper boy and had after the tenth grade quit high school to support the family. Still, nothing marked him as a man who would risk his own life to save the lives of others, but his country gave him an opportunity to serve and prove himself, and he did.

Before joining the CCC, my father had been a city boy, but in the Oregon woods he discovered a new world of great wonder. It enriched his life, just as his recollections of it enrich my own:

“Thunder and lightning are very dangerous in the forest. Well, one stormy night a Forest Ranger smoke chaser got a call from the fire tower. They spotted a small night fire; getting the location the Ranger took me and another CCC boy to check it out. After walking about a mile in the woods we spotted the fire. It had burned a circle of fire at least 100 yards in diameter from the impact of the lightning bolt.

“You never saw anything so beautiful. The trees were all lit in fire; the fire on the ground was lit up in hot coals. Also fiery embers were falling off the trees. Some of the trees were dried dead snags. It looked like the New York skyline lit up at night. The Ranger radioed back for a fire crew. Meanwhile the three of us started to contain the fire with a fire trail.

“Later, we got caught in a thunderstorm in the mountains. We stretched a tarpaulin to protect ourselves from the downpours. You could see the storm clouds, with thunder and lightning flashing, approaching and passing over us. Then the torrents of rain. It would stop and clear with stars shining. And sure enough it must have repeated the sequence at least five times. What a night.”

Jump ahead to 2008 and picture a nineteen-year-old high school dropout. Do you see a self-centered slacker, someone too preoccupied exercising his thumbs on video games, or advertising himself on MySpace and Facebook, to do much of anything to help anyone other than himself?

Sure, there are a few of these. Aren’t there always? But many more young Americans already serve or volunteer in some capacity. Even our imaginary slacker may just need an opportunity — and a little push — to prove his mettle. We’ll never know unless our leaders put our money where, at present, only their mouths are.

Remaking National Service — And Our Country

Today, when most people think of national service, they think of military service. As a retired military officer, I’m hardly one to discount the importance of such service, but we need to extend the notion of service beyond the military, beyond national defense, to embrace all dimensions of civic life. Imagine if such service was as much the norm as in the 1930s, rather than the exception, and imagine if our government was no longer seen as the problem, but the progenitor of opportunity and solutions?

Some will say it can no longer be done. Much like Rudy Giuliani, they’ll poke fun at the whole idea of service, and paint the government as dangerously corrupt, or wasteful, or even as the enemy of the people — perhaps because they’re part of that same government.

How sad. We don’t need jaded “insiders” or callow “outsiders” in Washington; what we need are doers and dreamers. We need leaders with faith both in the people — the common worker with uncommon spirit — and the government to inspire and get things done.

The unselfish idealism, work ethic, and public service of the CCC could be tapped again, if only our government remembers that our greatest national resource is not exhaustible commodities like oil or natural gas, but the inexhaustible spirit and generosity of the American worker.

William J. Astore, a retired lieutenant colonel (USAF), taught at the Air Force Academy and the Naval Postgraduate School. He now teaches at the Pennsylvania College of Technology, and is the author of Hindenburg: Icon of German Militarism (Potomac Press, 2005), among other works. He may be reached at wastore@pct.edu.

Copyright 2008 William Astore