Returning a Final Time to Cheyenne Mountain

DEC 02, 2025

Hello Everyone: In 2007, I was fed up with the lies of the Bush/Cheney administration and the way civilian leadership was using the bemedaled chest of David Petraeus to deflect blame for that disastrous war. I knew then the “success” of the surge was an illusion, or, as Petraeus put it back then, “fragile” and “reversible” (and so it proved to be). I wrote an op-ed about how we the people had to save the military from itself and its own self-serving illusions. No one was interested in what I had to say; no one, that is, except Tom Engelhardt at TomDispatch. And so that led to my first “tomgram.”

Eighteen years later, I’ve reached the unlikely number of 115 essays for TomDispatch, something neither Tom nor I ever expected. And just about all those essays have been introduced by a mini-essay by Tom himself. It’s been a remarkable partnership—it’s what got my career as a writer and essayist (rather than a traditional historian) started.

This piece, my 115th, returns again to Cheyenne Mountain and nuclear war. I first wrote about my time “in the mountain” in 2008; seventeen years later, I’m even more dismayed at (and disgusted by) my country’s newfound enthusiasm for nuclear weapons and their “recapitalization.” Read on!

*****

It’s been 20 years since I retired from the Air Force and 40 years since I first entered Cheyenne Mountain, America’s nuclear redoubt at the southern end of the Front Range that includes Pikes Peak in Colorado. So it was with some nostalgia that I read a recent memo from General Kenneth Wilsbach, the new Chief of Staff of the Air Force (CSAF). Along with the usual warrior talk, the CSAF vowed to “relentlessly advocate” for the new Sentinel ICBM (intercontinental ballistic missile) and the B-21 Raider stealth bomber. While the Air Force often speaks of “investing” in new nukes, this time the CSAF opted for “recapitalization,” a remarkably bloodless term for the creation of a whole new generation of genocidal thermonuclear weapons and their delivery systems.

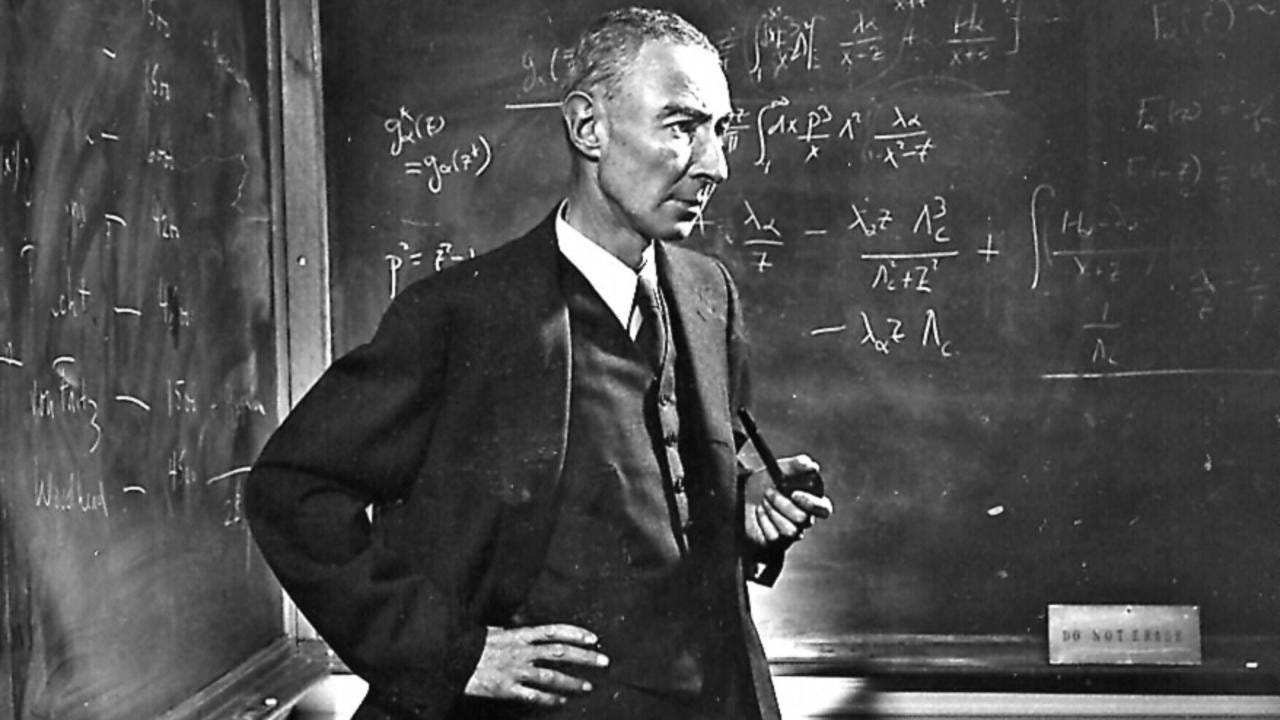

(Take a moment to think about that word, “creation,” applied to weapons of mass destruction. Raised Catholic, I learned that God created the universe out of nothing. By comparison, nuclear creators aren’t gods, they’re devils, for their “creation” may end with the destruction of everything. Small wonder J. Robert Oppenheimer musedthat he’d become death, the destroyer of worlds, after the first successful atomic blast in 1945.)

In my Cheyenne Mountain days, circa 1985, the new “must have” bomber was the B-1 Lancer and the new “must have” ICBM was the MX Peacekeeper. If you go back 20 to 30 years earlier than that, it was the B-52 and the Minuteman. And mind you, my old service “owns” two legs of America’s nuclear triad. (The Navy has the third with its nuclear submarines armed with Trident II missiles.) And count on one thing: it will never willingly give them up. It will always “relentlessly advocate” for the latest ICBM and nuclear-capable bomber, irrespective of need, price, strategy, or above all else their murderous, indeed apocalyptic, capabilities.

At this moment, Donald Trump’s America has more than 5,000 nuclear warheads and bombs of various sorts, while Vladimir Putin’s Russia has roughly 5,500 of the same. Together, they represent overkill of an enormity that should be considered essentially unfathomable. Any sane person would minimally argue for serious reductions in nuclear weaponry on this planet. The literal salvation of humanity may depend on it. But don’t tell that to the generals and admirals, or to the weapons-producing corporations that get rich building such weaponry, or to members of Congress who have factories producing such weaponry and bases housing them in their districts.

So, here we are in a world in which the Pentagon plans to spend another $1.7 trillion(and no, that is not a typo!) “recapitalizing” its nuclear triad, and so in a world that is guaranteed to remain haunted forever by a possible future doomsday, the specter of nuclear mushroom clouds, and a true “end-times” catastrophe.

I Join AF Space Command Only to Find Myself Under 2,000 Feet of Granite

My first military assignment in 1985 was at Peterson Air Force Base in Colorado with Air Force Space Command. That put me in America’s nuclear command post during the last few years of the Cold War. I also worked in the Space Surveillance Center and on a battle staff that brought me into the Missile Warning Center. So, I was exposed, in a relatively modest way (if anything having to do with nuclear weapons can ever be considered “modest”), to what nuclear war would actually be like and forced to think about it in a way most Americans don’t.

Each time I journeyed into Cheyenne Mountain, I walked or rode through a long tunnel carved out of granite. The buildings inside were mounted on gigantic springs (yes, springs!) that were supposed to absorb the shock of any nearby hydrogen bomb blast in a future war with the Soviet Union. Massive blast doors that looked like they belonged on the largest bank vault in the universe were supposed to keep us safe, though in a nuclear war they might only have ensured our entombment. They were mostly kept open, but every now and then they were closed for a military exercise.

I was a “space systems test analyst.” The Space Surveillance Center ran on a certain software program that needed periodic testing and evaluation and I helped test the computer software that kept track of all objects orbiting the Earth. Back then, there were just over 5,000 of them. (Now, that number’s more like 45,000 and space is a lot more crowded — perhaps too crowded.)

Anyhow, what I remember most vividly were military exercises where we’d run through different potentially world-ending scenarios. (Think of the movie War Gameswith Matthew Broderick.) One exercise simulated a nuclear attack on the United States. No, it wasn’t like some Hollywood production. We just had monochrome computer displays with primitive graphics, but you could certainly see missile tracks emerging from the Soviet Union, crossing the North Pole, and ending at American cities.

Even though there were no fancy (fake) explosions and no other special effects, simply realizing what was possible and how we would visualize it if it were actually to happen was, as I’m sure you can imagine, a distinctly sobering experience and not one I’ve ever forgotten.

That “war game” should have shaken me up more than it did, however. At the time, we had a certain amount of fatalism about the possibility of nuclear war, something captured in the posters of the era that told you what to do in case of a nuclear attack. The final step was basically to bend over and kiss your ass goodbye. That was indeed my attitude.

Rather than obsess about Armageddon, I submerged myself in routine. There was a certain job to be done, procedures to be carried out, discipline to adhere to. Remember, of course, that this was also the era of the rise of the nuclear freeze protest movement that was demanding the U.S. and the Soviet Union reach an agreement to halt further testing, production, and deployment of nuclear weapons. (If only, of course!) In addition, this was the time of the hit film The Day After, which tried to portray the aftermath of a nuclear war in the United States. In fact, on a midnight shift in Cheyenne Mountain, I even read Tom Clancy’s Red Storm Rising, which envisioned the Cold War gone hot, a Third World War gone nuclear.

Of course, if we had thought about nuclear war every minute of every day, we might indeed have been cowering under our sheets. Unfortunately, as a society, except in rare moments like the nuclear freeze movement one, we neither considered nor generally grasped what nuclear war was all about (even though nine countries now possess such weaponry and the likelihood of such a war only grows). Unfortunately, that lack of comprehension (and so protest) is one big reason why nuclear war remains so chillingly possible.

If anything, such a war has been eerily normalized in our collective consciousness and we’ve become remarkably numb to and fatalistic about it. One characteristic of that reality was the anesthetizing language that we used then (and still use) when it came to nuclear matters. We in the military spoke in acronyms or jargon about “flexible response,” “deterrence,” and what was then known as “mutually assured destruction” (or the wiping out of everything). In fact, we had a whole vocabulary of different words and euphemisms we could use so as not to think too deeply about the unthinkable or our possible role in making it happen.

My Date With Trinity

After leaving Cheyenne Mountain and getting a master’s degree, I co-taught a course on the making and use of the atomic bomb at the Air Force Academy. That was in 1992, and we actually took the cadets on a field trip to Los Alamos where the first nuclear weapon had largely been developed. Then we went on to the Trinity test sitein Alamogordo, New Mexico, where, of course, that first atomic device was tested and that, believe me, was an unforgettable experience. We walked around and saw what was left of the tower where Robert Oppenheimer and crew suspended the “gadget” (nice euphemism!) for testing that bomb on July 16, 1945, less than a month before two atomic bombs would be dropped on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, destroying both of them and killing perhaps 200,000 people. Basically (I’m sure you won’t be surprised to learn), nothing’s left of that tower except for its concrete base and a couple of twisted pieces of metal. It certainly does make you reflect on the sheer power of such weaponry. It was then and remains a distinctly haunted landscape and walking around it a truly sobering experience.

And when I toured the Los Alamos lab right after the collapse of the other great superpower of that moment, the Soviet Union, it was curious how glum the people I met there were. The mood of the scientists was like: hey, maybe I’m going to have to find another job because we’re not going to be building all these nuclear weapons anymore, not with the Soviet Union gone. It was so obviously time for America to cash in its “peace dividends” and the scientists’ mood reflected that.

Now, just imagine that 33 years after I took those cadets there, Los Alamos is once again going gangbusters, as our nation plans to “invest” another $1.7 trillion in a “modernized” nuclear triad (imagine what that means in terms of ultimate destruction!) that we (and the rest of the world) absolutely don’t need. To be blunt, today that outrages me. It angers me that all of us, whether those like me who served in uniform or your average American taxpayer, have sacrificed so much to create genocidal weaponry and a distinctly world-ending arsenal. Worse yet, when the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, we didn’t even try to change course. And now the message is: Let’s spend staggering amounts of our tax dollars on even more apocalyptic weaponry. It’s insanity and, no question about it, it’s also morally obscene.

The Glitter of Nuclear Weapons

That ongoing obsession with total destruction, ultimate annihilation, reflects the fact that the United States is led by moral midgets. During the Vietnam War years, the infamous phrase of the time was that the U.S. military had to “destroy the town to save it” (from communism, of course). And for 70 years now, America’s leaders have tacitly threatened to order the destruction of the world to save it from a rival power like Russia or China. Indeed, nuclear war plans in the early 1960s already envisioned a massive strike against Russia and China, with estimates of the dead put at 600 million, or “100 Holocausts,” as Daniel Ellsberg of Vietnam War fame so memorably put it.

Take it from this retired officer: you simply can’t trust the U.S. military with that sort of destructive power. Indeed, you can’t trust anyone with that much power at their fingertips. Consider nuclear weapons akin to the One Ring of Power in J.R.R. Tolkien’s The Lord of the Rings. Anyone who puts that ring on is inevitably twisted and corrupted.

Freeman Dyson, a physicist of considerable probity, put it well to documentarian Jon Else in his film The Day After Trinity. Dyson confessed to his own “ring of power” moment:

“I felt it myself. The glitter of nuclear weapons. It is irresistible if you come to them as a scientist. To feel it’s there in your hands, to release this energy that fuels the stars, to let it do your bidding. To perform these miracles, to lift a million tons of rock into the sky. It is something that gives people an illusion of illimitable power, and it is, in some ways, responsible for all our troubles — this, what you might call technical arrogance, that overcomes people when they see what they can do with their minds.”

I’ve felt something akin to that as well. When I wore a military uniform, I was in some sense a captive to power. The military both captures and captivates. There’s an allure of power in the military, since you have a lot of destructive power at your disposal.

Of course, I wasn’t a B-1 bomber pilot or a missile-launch officer for ICBMs, but even so, when you’re part of something that’s so immensely, even world-destructively powerful, believe me, it does have an allure to it. And I don’t think we’re usually fully aware of how captivating that can be and how much you can want to be a part of that.

Even after their service, many veterans still want to go up in a warplane again or take a tour of a submarine, a battleship, or an aircraft carrier for nostalgic reasons, of course, but also because you want to regain that captivating feeling of being so close to immense — even world-ending — power.

The saying that “power corrupts, and absolute power corrupts absolutely” may never be truer than when it comes to nuclear war. We even have expressions like “use them or lose them” to express how ICBMs should be “launched on warning” of a nuclear attack before they can be destroyed by an incoming enemy strike. So many years later, in other words, the world remains on even more of a nuclear hair-trigger, the pistol loaded and cocked to our collective heads, just waiting for news that will push us over the edge, that will make those trigger fingers of ours too itchy to resist the urge to put too much pressure on that nuclear trigger.

No matter how many bunkers we build, no matter that the world’s biggest bunker tunneled out of a mountain, the one I was once in, still exists, nothing will save us if we allow the glitter of nuclear weapons to flash into preternatural thermonuclear brightness.

Copyright 2025 William J. Astore