W.J. Astore

I’m still waiting for the blockbuster Hollywood production that celebrates peace

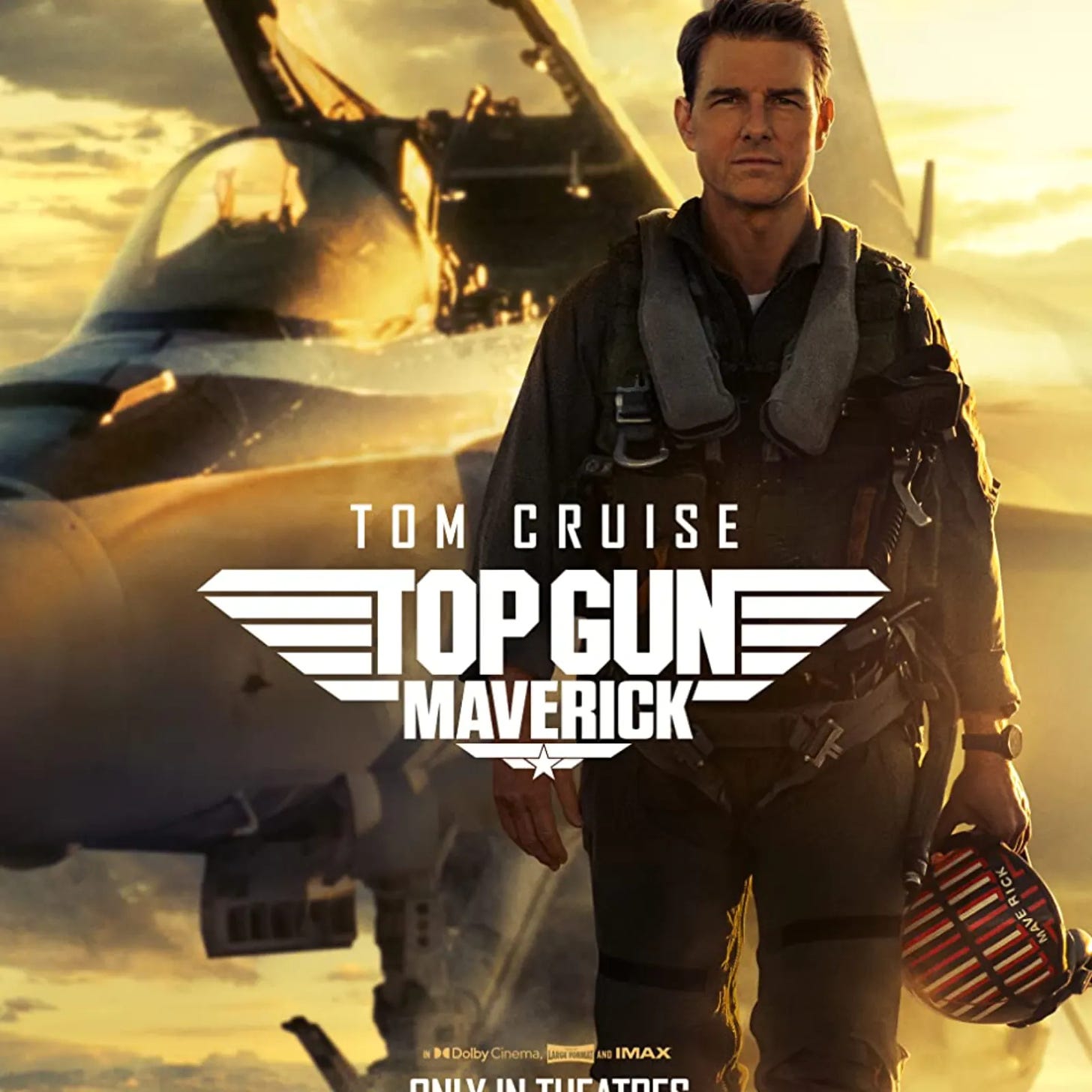

Last year, “Top Gun: Maverick” was all the rage. It was a silly war flick with a plot ripped from the original “Star Wars” movie featuring plenty of bloodless, high octane action sequences. I enjoyed it in the way I occasionally indulge in unhealthy fast food. The movie was instantly forgettable except for one scene where hotshot pilot Maverick, played of course by Tom Cruise, meets his old rival Iceman, played by Val Kilmer. In real life, Kilmer suffers from throat cancer, and his condition is not hidden in the movie, where Kilmer is now an admiral who still believes in his old friend, Captain Pete “Maverick” Mitchell.

Naturally, Maverick saves the day, pummeling a nameless enemy (most likely Iran) with bombs because that country is developing nuclear weapons. Nothing, of course, is said of the thousands of nuclear warheads and bombs in America’s arsenal, or that the USA is the only country to have used atomic bombs in war (Hiroshima, Nagasaki). But I digress.

Hollywood loves war movies. They sell well. Yet I still await “Top Dove: Peacenik,” in which an intrepid, brave, determined, and charismatic person stops a war without bombing or killing anyone. What a breath of fresh air that would be!

Exactly ten years ago, I posted the article below at Bracing Views. We need peacemakers now more than ever. Sadly, they are still very much forgotten, or ignored, or dismissed as unserious or even delusional.

Forgotten Are the Peacemakers (2013)

Being Catholic, I’m a big fan of the Sermon on the Mount and Christ’s teaching that “blessed are the peacemakers.” Yet in American history it seems that “forgotten are the peacemakers” would be a more accurate lesson. We’re much more likely to remember “great” generals, even vainglorious ones like George S. Patton or Douglas MacArthur, than to recognize those who’ve fought hard against long odds for peace.

Elihu Burritt was one such peacemaker. Known in his day as “The Learned Blacksmith,” Burritt fought for peace and against slavery in the decades before the Civil War in the United States. He rose from humble roots to international significance, presiding over The League of Universal Brotherhood in the 1840s and 1850s while authoring many books on humanitarian subjects.

Interestingly, peacemakers like Burritt were often motivated by evangelical Christianity. They saw murder as a sin and murderous warfare as an especially grievous manifestation of man’s sinfulness. Many evangelicals of his day were also inspired by their religious beliefs to oppose slavery as a vile and reprehensible practice.

Christian peacemakers like Burritt may not have had much success, but they deserve to be remembered and honored as much as our nation’s most accomplished generals. That we neglect to honor men and women like Burritt says much about America’s character.

For if we truly are a peace-loving people, why do we fail to honor our most accomplished advocates for peace?