W.J. Astore

Francis Bacon is famous for the aphorism, “Knowledge is power.” Yet the reverse aphorism is not true. The United States is the most powerful nation in the world, yet its knowledge base is notably weak in spite of all that power. Of course, many factors contribute to this weakness. Our public educational systems are underfunded and driven by meaningless standardized test results. Our politicians pander to the lowest common denominator. Our mainstream media is corporate-owned and in the business of providing info-tainment when they’re not stoking fear. Our elites are in the business of keeping the American people divided, distracted, and downtrodden, conditions that do not favor critical thinking, which is precisely the point of their efforts.

All that is true. But even when the U.S. actively seeks knowledge, we get little in return for our investment. U.S. intelligence agencies (the CIA, NSA, DIA, and so on) aggregate an enormous amount of data, then try to convert this to knowledge, which is then used to inform action. But these agencies end up drowning in minutiae. Worse, competing agencies within a tangled bureaucracy (that truly deserves the label of “Byzantine”) end up spinning the data for their own benefit. The result is not “knowledge” but disinformation and self-serving propaganda.

When our various intelligence agencies are not drowning in minutiae or choking on their own “spin,” they’re getting lost in the process of converting data to knowledge. Indeed, so much attention is put on process, with so many agencies being involved in that process, that the end product – accurate and actionable knowledge – gets lost. Yet, as long as the system keeps running, few involved seem to mind, even when the result is marginal — or disastrous.

Consider the Vietnam War. Massive amounts of “intelligence” data took the place of knowledge. Data like enemy body counts, truck counts, aircraft sorties, bomb tonnages, acres defoliated, number of villages pacified, and on and on. Amassing this data took an enormous amount of time; attempting to interpret this data took more time; and reaching conclusions from the (often inaccurate and mostly irrelevant) data became an exercise in false optimism and self-delusion. Somehow, all that data suggested to US officialdom that they were winning the war, a war in which US troops were allegedly making measurable and sustained progress. But events proved such “knowledge” to be false.

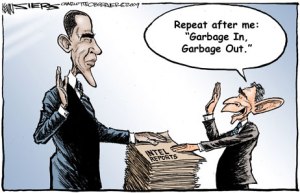

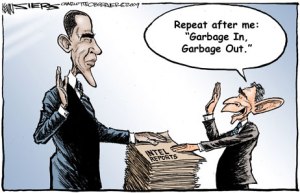

Of course, there’s an acronym for this: GIGO, or garbage (data) in, garbage (knowledge) out.

In this case, real knowledge was represented by the wisdom of Marine Corps General (and Medal of Honor recipient) David M. Shoup, who said in 1966 that:

I don’t think the whole of Southeast Asia, as related to the present and future safety and freedom of the people of this country, is worth the life or limb of a single American [and] I believe that if we had and would keep our dirty bloody dollar-crooked fingers out of the business of these nations so full of depressed, exploited people, they will arrive at a solution of their own design and want, that they fight and work for. And if, unfortunately, their revolution must be of the violent type…at least what they get will be their own and not the American style, which they don’t want…crammed down their throat.

But few wanted to hear Shoup and his brand of hard-won knowledge, even if he’d been handpicked by President Kennedy to serve as the Commandant of the Marine Corps exactly because Shoup had a reputation for sound and independent thinking.

Consider as well our rebuilding efforts in Iraq after 2003. As documented by Peter Van Buren in his book “We Meant Well,” those efforts were often inept and counterproductive. Yet the bureaucracy engaged in those efforts was determined to spin them as successes. They may even have come to believe their own spin. When Van Buren had the clarity and audacity to say, We’re fooling no one with our Kabuki dance in Iraq except the American people we’re sworn to serve, he was dismissed and punished by the State Department.

Why? Because you’re not supposed to share knowledge, real knowledge, with the American people. Instead, you’re supposed to baffle them with BS. But Van Buren was having none of that. His tell-all book (you can read an excerpt here) captured the Potemkin village-like atmosphere of US rebuilding efforts in Iraq. His accurate knowledge had real power, and for sharing it with the American people he was slapped down.

Tell the truth – share real knowledge with the American people – and you get punished. Massage the data to create false “knowledge,” in these cases narratives of success, and you get a pat on the back and a promotion. Small wonder that so many recent wars have gone so poorly for America.

What the United States desperately needs is insight. Honesty. A level of knowledge that reflects mastery. But what we’re getting is manufactured information, or disinformation, or BS. Lies, in plainspeak, like the lie that Iraq had in 2002 a large and active program in developing WMD that could be used against the United States. (Remember how we were told we had to invade Iraq quickly before the “smoking gun” became a “mushroom cloud”?)

If knowledge is power, what is false knowledge? False knowledge is a form of power as well, but a twisted one. For when you mistake the facade you’re constructing as the real deal, when you manufacture your own myths and then forget they’re myths as you consume them, you may find yourself hopelessly confused, even as the very myths you created consume you.

So, a corollary to Francis Bacon: Knowledge is power, but as the United States has discovered in Vietnam, Iraq, and elsewhere, power is no substitute for knowledge.