M. Davout

Agency and autonomy are fundamental to democracy. Panic is fundamental to fear and chaos. Preserving personal agency while avoiding panicked reactions is one of the great challenges ahead of us. While the Covid pandemic will burn itself out, America’s pandemic of panic–manifested in the rise of wild and often evidence-free conspiracies–continues to accelerate. How much misinformation and mistrust can America tolerate before democracy itself crashes around us? Our very own M. Davout, who teaches political science, introduces the concept of “agency panic” and challenges us to take the red pill of uncomfortable truths. W.J. Astore

America’s Twin Pandemics of Covid and Agency Panic

M. Davout

America is awash in conspiracy thinking and it is doing terrible damage to the country. However, the solution is not to dismiss conspiracy thinking altogether but to distinguish fake conspiracies from real ones.

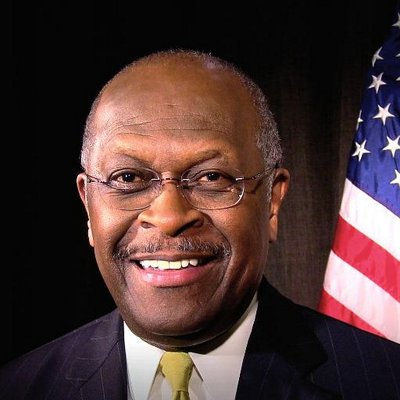

Consider the many theories afloat about Covid-19. Scrolling through the Facebook posts of anti-maskers and anti-vaxxers curated on the Herman Cain Award subreddit, one is struck by the sheer quantity of conspiratorial memes circulating among networks of likeminded Facebook friends. The Covid pandemic is variously presented as the product of a nefarious plot enacted by the Chinese government or by the US government or by the Centers for Disease Control or…the list goes on. Public health measures that have been recommended or mandated at the federal, state or local levels such as quarantining, masking, and vaccinating are similarly condemned as elements of the conspiratorial machinations of Anthony Fauci or Bill Gates (or both of them working in cahoots), of profiteering Big Pharma, of collectivizing communists, of Medicare-For-All socialists, and so on.

As Richard Hofstadter demonstrated in his famous essay, “The Paranoid Style in American Politics,” the United States has from very early in its history provided fertile ground for the organized circulation of political rhetoric warning in shrill tones about the impending takeover of the political system. Alleged nefarious groups named in these conspiracy theories included the Illuminati, the Freemasons, papists, Jesuits, anarchists, Jews, international financiers, and communists.

While the anti-mask and anti-vax conspiracies circulating on Facebook today manifest the characteristics of “heated exaggeration, suspiciousness, and conspiratorial fantasy” which Hofstadter identified as typical of the paranoid style, the sense of what is at stake has changed. It is no longer just constitutional government that seems to be at risk. When you read the conspiratorial warnings available across the ideological spectrum—from QAnon enthusiasts or Trumpist dead-enders or health purists or anti-corporate populists, among others—you get the sense that people feel their very identities to be under threat. Has a threshold been passed that separates the conspiracy-mongers of today from their anti-papist, anti-Masonic forebearers?

In his book, Empire of Conspiracy: The Culture of Paranoia in Postwar America (2000), Timothy Melley argued that conspiracy thinking fundamentally changed after World War II with the rise of the “information age.” Consumers of electronic mass media became susceptible to what he characterized as a state of “agency panic,” an “intense anxiety about an apparent loss of autonomy or self-control” in the face of pernicious systems of social control acting with a singular will. Notions of secret plots hatched by bands of conspirators aiming at the conquest of political power were increasingly replaced by visions of “whole populations being openly manipulated without their knowledge” through the effects of advertising, schooling, fluoridation, and so on. The USA was ground zero for this new form of conspiratorial thinking because the American embrace of the idea of rugged individualism was so at odds with the reality of an increasingly interdependent society in which self-sufficient farmers were a dying breed.

Empire of Conspiracy was published at the dawn of the surveillance economy ushered in by Google and Facebook. This economy has at the same time systematically perfected the relentless tracking of individual activities and facilitated the exchange of conspiratorial memes and messages lamenting the threats to individual integrity and freedom. Paranoid messages that are likely to attract eyes are moved algorithmically to the top of search results or share lists. The Covid pandemic has only supercharged these developments by boosting mass dependence on the internet and amplifying mass grievance against infringements on individual freedoms.

The easy response to this internet-fueled conspiratorial dynamic would be to dismiss conspiracy thinking as the paranoid raving of the uneducated and ignorant if it weren’t for the fact that real conspiracies are continually afoot in our political system. One has only to take note of the ever-accelerating revolving door between public officialdom and the lobbying-industrial complex or to monitor the ever-greater lobbying and campaign expenditures of major industries such as Big Pharma or Big Coal or Big Tech to know that well-paid influencers are working diligently with corrupted politicians to poach the common good.

Yet the rising tide of agency panic-driven conspiratorial thinking continually diverts Americans from the true causes of their collective misery into attacks on those few public measures that are in our collective interest.

It truly is a choice between taking the red pill or the blue pill, as The Matrix meme circulated by so many of the Covid conspiracy Facebook posters suggests. But, against their expectation, taking the red pill would lead to a clear-eyed understanding of how corporate influence peddling diminishes our lives rather than to a revelation that supposed college roommates Bill Gates and Anthony Fauci hatched a conspiracy against our freedoms fifty years ago.

M. Davout, an occasional contributor to Bracing Views, teaches political science at the collegiate level.