Lessons from My Dad

W.J. Astore

Hi Everyone: If you’d like to support this site but don’t want to subscribe and pay a yearly fee, perhaps you’d consider my new book, My Father’s Journal, available through Amazon for $10 (paperback) or $5 (Kindle). Just click on that link and order away. Order five copies for your dad! (Yes, that’s reference to a song lyric, “Gonna buy five copies for my mother.”)

Anyhow, here’s an except from the book, which details my father’s efforts to fight raging forest fires on the West Coast in Oregon and California during the 1930s. His account will likely remind you of the recent fires in LA.

A big “thank you” to those who order the book—I hope you enjoy it.

*****

It is surprising how many forest fires our crew fought and other groups that we assisted in the two summers I was in Oregon.

The main and largest fire we fought was in the fall of 1936. A very dry summer and fall added to the fire danger. We were in Enterprise, Oregon when we got our call to go to Bandon “By the Sea” Oregon. Enterprise is in the northeast corner of the state. The day before, Bandon had been swept by the forest fire. Twelve people lost their lives. It could have been much worse but all inhabitants fled to the ocean beaches. One pregnant lady gave birth to a baby on the beach.

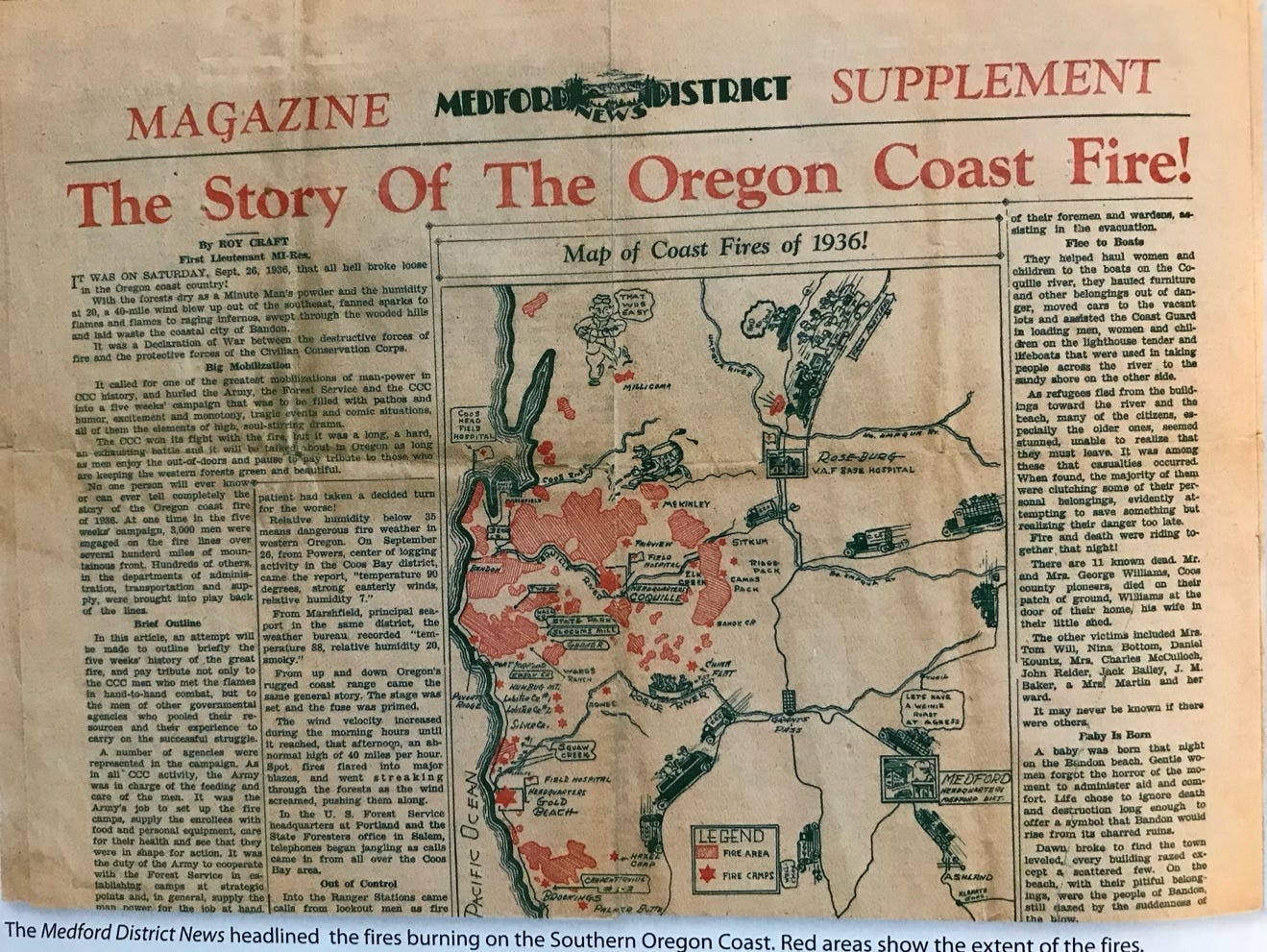

Fifty of the men in our camp, using 2.5-ton trucks, traveled across the state (guessing approximately 300 miles). The areas were involved in hundreds of fires that covered an area greater than the state of Massachusetts.

We were on the fire lines for over five weeks. At times we were put on reserve where we could shower and shave. We had about 5000 men, woodsmen, rangers, and CCC boys fighting this fire.

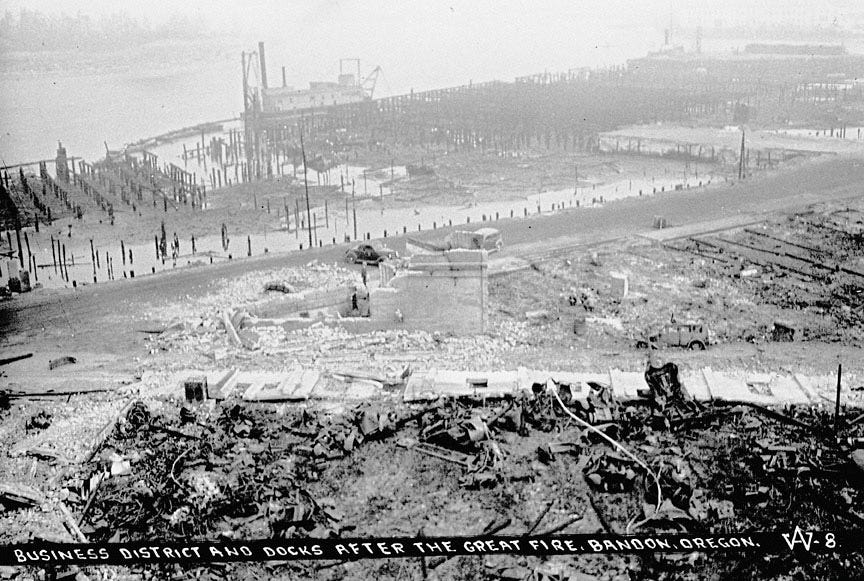

We were at Gold Beach, Oregon and we could look into California at the Siskiyou Mt. Range. There was a rumor we were going to fight a fire in the redwoods of California. But the call never came. We drove through Bandon; there were rows and rows of dwellings, gas stations and buildings burned to the ground. Quite a few chimneys were still standing. Every once in a while you’d see a dwelling or building spared by the fire. Just a whim of fate.

My father was a great saver of documents, including in this case The Medford District News, a local newspaper in Oregon that devoted two full pages to the five-week campaign to contain the Bandon Fires of 1936.[i] Written by Roy Craft, a first lieutenant, the story is worth quoting at length:

It was on Saturday, Sept. 26, 1936, that all hell broke loose in the Oregon coast country! With the forests dry as a Minute Man’s powder and the humidity at 20%, a 40-mile wind blew up out of the southeast, swept through the wooded hills and laid waste the coastal city of Bandon. It was a Declaration of War between the destructive forces of fire and the protective forces of the Civilian Conservation Corps….

As in all CCC activity, the Army oversaw the feeding and care of the men. It was the Army’s job to set up the fire camps, supply the enrollees with food and personal equipment, care for their health and see that they were in shape for action….

[Later that night] the fire had swept up to the very edge of the city. Then, borne on the shoulders of the 40-mile wind, the flames rode into Bandon. The Bandon fire department and the CCC men made a desperate stand but normal fire equipment was no match for the blaze.

As the fire approached the town, many residents were still unaware of the impending tragedy and had gone to the local theatre to see the feature picture, “Thirty-Six Hours to Live.” The film didn’t last that long, for in the middle of the show the film was stopped and a call was made for volunteer fire fighters.

As the fire poured into Bandon, building after building went up in flames. The residents literally “ran for their lives,” with men of the CCC … assisting in the evacuation.

Photo available at https://www.oregonhistoryproject.org/articles/historical-records/bandon-fire-1936/

Many people escaped in boats across the Coquille River, but the fire claimed at least eleven lives. As my father mentioned, a baby was indeed born that very night on the beach, which was taken as a “symbol that Bandon would rise from it charred ruins,” according to a somewhat fanciful newspaper account.

More than 100,000 acres burned over a period of five weeks until the November rains came to extinguish the flames for good. (Dad penned a quick postcard, dated 10/26/36, to tell the family he was fine and that he’d “been out fighting forest fires for over a month now.”)

As LT Craft put it in his newspaper account,

Anybody can play at being a hero for a couple of hours, or face trying and dangerous situations when the stimulus of excitement makes them glamorous and daring. But it takes guts to put out day after day on the fire line! Nothing tests a man’s mettle like a five weeks’ siege with fire, when it’s drudgery to put in a day and a night on the line, sleep a few hours on the hard ground, and then crawl out again and go back to pitch in with shovel, hazel hoe and back pump.

The Bandon Fire was the largest that my father faced, and he spoke of it often.

(If you’d like to order the book, here’s that link again. Thanks!)