W.J. Astore

Empty Boasts of Having the “World’s Best” Military Hide Rot, Waste, and Stupidity

Sixteen years ago, I made a plea to my fellow citizens to banish the word “warfighter” from our vocabulary. I asked that we stop referring to the U.S. military as the “world’s best,” an empty boast then and, after twin disasters in Iraq and Afghanistan, an emptier one today. (If something can indeed be “emptier,” it’s certainly bellicose boasts of alleged military brilliance.) Today’s military is overstretched, busy guaranteeing Israel’s security as the Israeli Defense Forces demolish and depopulate Gaza. Facing recruiting shortfalls, open-ended imperial commitments across the globe, and fears of hostilities with Russia, China, Iran, or an almost unimaginable and certainly unbeatable combination of the three, the U.S. military faces grim times. If leaders like President Biden truly want to protect “our” troops, they should look not to God but in the mirror. They should pursue peace through diplomacy while downsizing an unsustainable empire. Isn’t it finally time for “Generation Warfighter” to come to an end before the U.S. military is utterly hollowed out — and America with it?

Having the “Best Military” Is Not Always a Good Thing

Reclaiming Our Citizen-Soldier Heritage

By William J. Astore

[Originally posted at TomDispatch in July of 2008]

When did American troops become “warfighters” — members of “Generation Kill” — instead of citizen-soldiers? And when did we become so proud of declaring our military to be “the world’s best”? These are neither frivolous nor rhetorical questions. Open up any national defense publication today and you can’t miss the ads from defense contractors, all eagerly touting the ways they “serve” America’s “warfighters.” Listen to the politicians, and you’ll hear the obligatory incantation about our military being “the world’s best.”

All this is, by now, so often repeated — so eagerly accepted — that few of us seem to recall how against the American grain it really is. If anything — and I saw this in studying German military history — it’s far more in keeping with the bellicose traditions and bumptious rhetoric of Imperial Germany under Kaiser Wilhelm II than of an American republic that began its march to independence with patriotic Minutemen in revolt against King George.

So consider this a modest proposal from a retired citizen-airman: A small but meaningful act against the creeping militarism of the Bush years would be to collectively repudiate our “world’s best warfighter” rhetoric and re-embrace instead a tradition of reluctant but resolute citizen-soldiers.

Becoming Warfighters

I first noticed the term “warfighter” in 2002. Like many a field-grade staff officer, I spent a lot of time crafting PowerPoint briefings, trying to sell senior officers and the Pentagon on my particular unit’s importance to the President’s new Global War on Terrorism. The more briefings I saw, the more often I came across references to “serving the warfighter.” It was, I suppose, an obvious selling point, once we were at war in Afghanistan and gearing up for “regime-change” in Iraq. And I was probably typical in that I, too, grabbed the term for my briefings. After all, who wants to be left behind when it comes to supporting the troops “at the pointy end of the spear” (to borrow another military trope)?

But I wasn’t comfortable with the term then, and today it tastes bitter in my mouth. Until recent times, the American military was justly proud of being a force of citizen-soldiers. It didn’t matter whether you were talking about those famed Revolutionary War Minutemen, courageous Civil War volunteers, or the “Greatest Generation” conscripts of World War II. After all, Americans had a long tradition of being distrustful of the very idea of a large, permanent army, as well as of giving potentially disruptive authority to generals.

Our tradition of citizen-soldiery was (and could still be) one of the great strengths of this country. Let me give you two examples of such citizen-soldiers, well known within military circles because they wrote especially powerful memoirs. Eugene B. Sledge served in the U.S. Marines during World War II, surviving two unimaginably brutal campaigns on the islands of Peleliu and Okinawa. His memoir With the Old Breed is arguably the best account of ground warfare in the Pacific. After three years of selfless, heroic service to his country, Sledge gladly returned to civilian life, eventually becoming a professor of biology. His conclusion — that “war is brutish, inglorious, and a terrible waste” — is one seconded by many a combat veteran.

Richard (Dick) Winters is better known because his exploits were captured in the HBO series Band of Brothers. He rose from platoon commander to battalion commander, serving in the elite 101st Airborne Division during World War II. A hero beloved by his men, Winters wanted nothing more than to quit the military and return to the civilian world. After the war, he lived a quiet life as a businessman in Pennsylvania, rarely mentioning his service and refusing to use his military rank for personal gratification. In Beyond Band of Brothers, he recounts both his service and his ideas on leadership. It’s a book to put in the hands of any young American who wishes to understand the noble ideas of service and sacrifice.

Sledge and Winters were regular guys who answered their country’s call. What comes across in their memoirs, as well as in the many letters I’ve read from World War II soldiers, was the desire of the average dogface to win the war, return home, hang up the uniform, and never again fire a shot in anger. These men were war-enders, not warfighters. Indeed, they would’ve been sickened by the very idea of being “warfighters.”

The term “warfighter” — a combination, I suppose, of “warrior” and “war fighting” — suggests a person who lives for war, who spoils for a fight. Certainly, the United States has fought its share of ruthless wars. But traditionally our soldiers have thought of themselves as civilians first, soldiers second. Equally as important, the American people thought of their troops that way.

Why are we now, with so little debate, casting aside an ethos that served us well for two centuries for one that straightforwardly embraces war and killing? Possibly because we’ve invented a distinctly American product: sanitized militarism. I bumped into it last week at a most unlikely place.

Visiting Gettysburg

Last week, I finally made it to Gettysburg, site of the great three-day battle between Union and Confederate forces in July 1863 that ended with the defeat of General Robert E. Lee’s army. Walking the battlefield was a sobering experience. I found myself on Little Round Top at 5:00 PM, just about the time of day that Union generals rushed men to reinforce the hill against a determined Confederate assault at the close of the battle’s second day. Earlier, I was at the Angle, just when, almost a century and a half ago, Pickett’s Charge failed to pierce the Union center, sealing Lee’s fate on the third day.

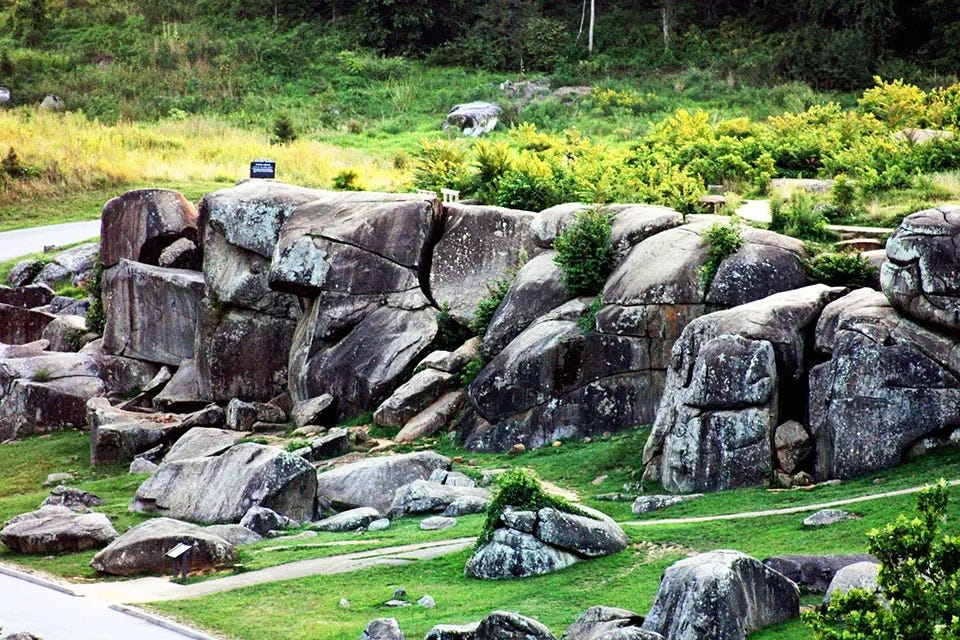

As these events played through my mind, I marveled that I had the battlefield largely to myself. Not that I was alone, mind you. Tour buses circled; cars, trucks, and SUVs whizzed about, but many, perhaps most, Americans who visit Gettysburg get surprisingly little tactile or sensory experience of its difficult topography. Yes, a few kids (and fewer adults) joined me in clambering about the huge, claustrophobically placed boulders of Devil’s Den, and I did spy a couple of guided tour groups on foot. But at the site of a bloodcurdling, distinctly septic nineteenth century battle, most visitors were clearly having a distinctly bloodless, even antiseptic, twenty-first century experience.

That day, I learned a lot about Gettysburg the battle — and maybe a little about us as well. As surely as my fellow tourists were staying in their cars and buses, we, as a people, are distancing ourselves from the realities of war. As we seal ourselves away from war’s horrors, we’re correspondingly finding it easier to speak of “warfighters” and to boast of having the world’s best military.

As we catch a glimpse, from the comfort of our living rooms, of a suicide bombing in Iraq or an American outpost attacked, then abandoned, in Afghanistan, are we not like those tourists in buses at Gettysburg, listening to sanitized recordings telling us what to see and think about the (expurgated) reality in front of us? And who dares challenge the “expert” commentary? Who dares turn off the canned talking heads and stare into the face of war?

But if we are to end our militaristic, yet curiously sanitized, “warfighter” moment, if we are ever to return to our citizen-soldier ethos and heritage, this is just what we must do.

After all, it’s later than you think. Our military now relies not only on a volunteer (if, at times, “stop-lossed”) Army, but increasingly on tens of thousands of hired guns, consultants, interrogators, interpreters, and other paramilitary camp followers. Private, for-profit “security contractors” — companies like Blackwater and Triple Canopy — give a disturbing new meaning to our “warfighter” terminology and the rhetoric that marches in step with it. As even casual students of history will recall, a clear sign of the Roman Empire’s decline was its shift from citizen-soldiers motivated by duty to mercenaries motivated by profit.

Replacing “warfighters” with true citizen-soldiers in the mold of Sledge and Winters would hardly be a solve-all solution at this late date, but it might be a step in the right direction — however unlikely it is to happen. For when we look at our troops, if we don’t see ourselves, then we see aliens or, worse yet, superiors (“warfighters”) in need of “support.” And that’s a clear sign of trouble for the republic.

Want to Be in the “World’s Best Military”? Ask German Veterans

It may come as a shock to some, but the American army wasn’t the best in the field in World War I, or World War II either. And thank heavens for that.

The distinction falls to the Kaiser Wilhelm’s army in 1914, and to Hitler’s Wehrmacht in 1941. Even toward the end of World War II, the American army was still often outmaneuvered and outclassed by its German foe. Because victory has a way of papering over faults and altering memories, few but professional historians today recall the many shortcomings of our military in both world wars.

But that’s precisely the point: The American military made mistakes because it was often ill-trained, rushed into combat too quickly, and handled by officers lacking in experience. Put simply, in both World Wars it lacked the tactical virtuosity of its German counterpart.

But here’s the question to ponder: At what price virtuosity? In World War I and World War II, the Germans were the best soldiers because they had trained and fought the most, because their societies were geared, mentally and in most other ways, for war, because they celebrated and valued feats of arms above all other contributions one could make to society and culture.

Being “the best soldiers” meant that senior German leaders — whether the Kaiser, Field Marshal Paul von Hindenburg, that Teutonic titan of World War I, or Hitler — always expected them to prevail. The mentality was: “We’re number one. How can we possibly lose unless we quit — or those [fill in your civilian quislings of choice] stab us in the back?”

If this mentality sounds increasingly familiar, it’s because it’s the one we ourselves have internalized in these last years. German warfighters and their leaders knew no limitations until it was too late for them to recover from ceaseless combat, imperial overstretch, and economic collapse.

Today, the U.S. military, and by extension American culture, is caught in a similar bind. After all, if we truly believe ours to be “the world’s best military” (and, judging by how often the claim is repeated in the echo chamber of our media, we evidently do), how can we possibly be losing in Iraq or Afghanistan? And, if the “impossible” somehow happens, how can our military be to blame? If our “warfighters” are indeed “the best,” someone else must have betrayed them — appeasing politicians, lily-livered liberals, duplicitous and weak-willed allies like the increasingly recalcitrant Iraqis, you name it.

Today, our military is arguably the world’s best. Certainly, it’s the world’s most powerful in its advanced armaments and its ability to destroy. But what does it say about our leaders that they are so taken with this form of power? And why exactly is it so good to be the “best” at this? Just ask a German military veteran — among the few who survived, that is — in a warrior-state that went berserk in a febrile quest for “full spectrum dominance.”

Fighting to End Wars

Words matter. Let’s start by banishing the word “warfighter,” and, while we’re at it, let’s toss out that “world’s best” boast as well. Boasting about military prowess is more Spartan than Athenian, more Second and Third Reich Germany than republican and democratic America.

Indeed, imagine, for a moment, a world in which the U.S. is no longer “number one” in military might (and, at the same time, no longer fighting endless wars in the Middle East and Central Asia). Would we then be weak and vulnerable? Or would we become stronger precisely because we stopped boasting about our ability as “warfighters” to dominate far from our shores and instead redirected our resources to developing alternative energy, bolstering our education system, reviving American industry, and focusing on other “soft power” alternatives to weapons and warriors? In other words, alternatives we can actually boast about with the pride of accomplishment.

Think about it: Must our military forever remain “second to none” for you to feel safe? Our national traditions suggest otherwise. In fact, if we no longer had the world’s strongest military, perhaps we would be more reluctant to tap its strength — and more hesitant to send our citizen-soldiers into harm’s way. And while we’re at it, perhaps we’d also learn to boast about a new kind of “warfighter” — not one who fights our wars, but one who fights against them.

Copyright 2008 William Astore.