With Some Follow-on Thoughts

Back in June of 2023, I wrote a letter to my archdiocese in response to a request for money. (I am a lapsed Catholic who has in the past given money to the Church.) Here is the letter I wrote, with some follow-on thoughts:

*****

June 2023

Most Reverend ***

Archdiocese of Boston

Dear Reverend ***

I received your Catholic Appeal funding letter dated June 1st. I won’t be contributing…

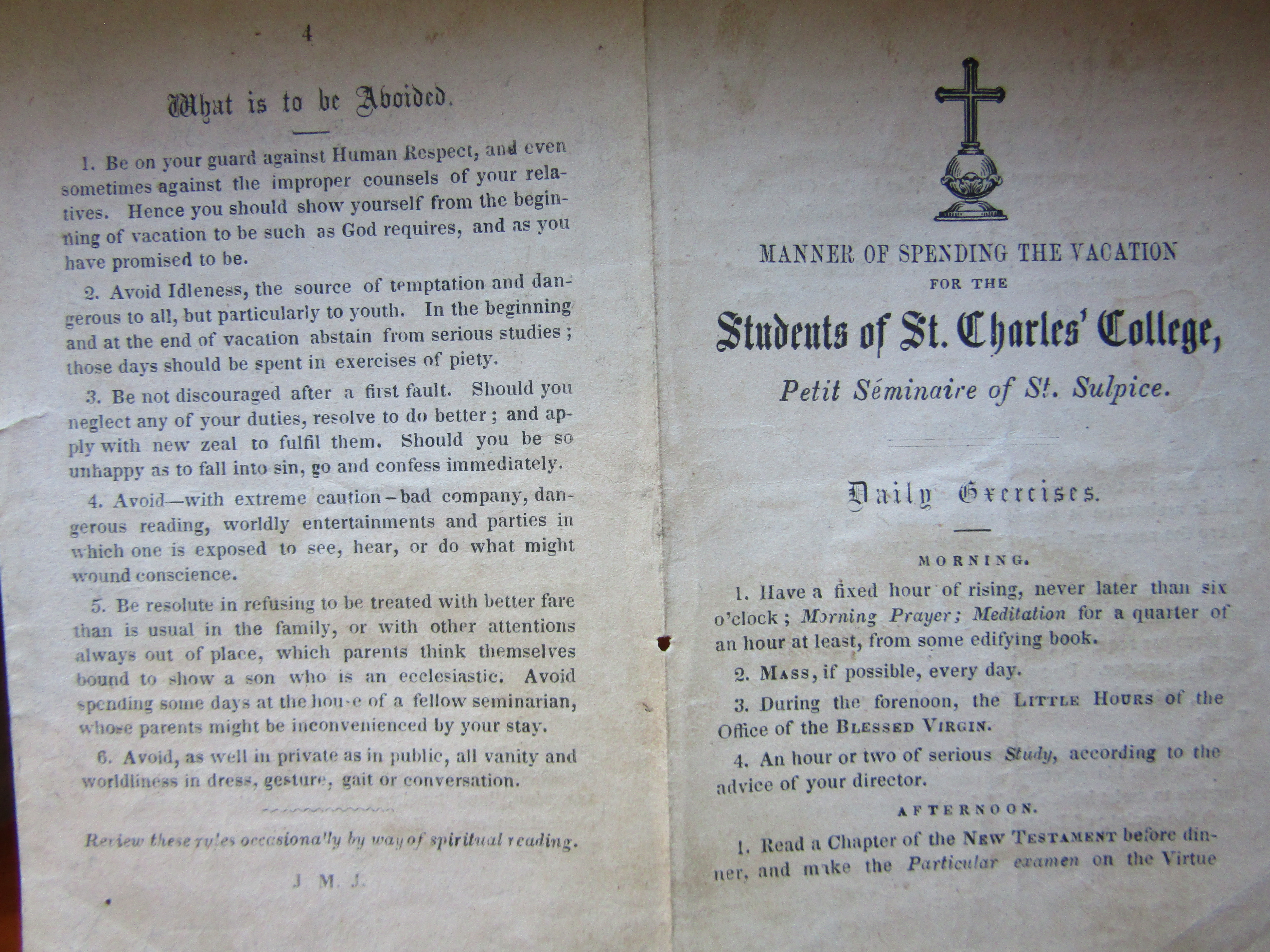

[Well into the 1990s,] I took my Catholic faith seriously; in fact, my master’s thesis at Johns Hopkins, which examined Catholic responses to science in the mid-19th century, especially Darwinism, geology, and polygenism, was published in the Catholic Historical Review. But scandals involving the Church drove me to question my commitment to Catholicism and especially its patriarchal hierarchy, which was so intimately involved in the coverups of crimes committed against innocents.

I grew up in Brockton, Mass., where the archdiocese assigned a predatory priest to our church of St. Patrick’s. His name was Robert F. Daly. He abused minors and was eventually defrocked by the Church, but far too late. (See the Boston Globe, 6/14/11.)

When I attended St. Patrick’s in the 1970s, Father Daly was teaching CCD. A sexual predator was attempting to teach young people the meaning of Christian love. He had a decent definition for love, something like “giving, without expecting anything in return.” Selfless love, I suppose. Tragically, he obviously failed catastrophically to practice what he preached.

Fortunately, I was never abused. I was supposed to have one meeting with him, alone, that was cancelled at the last minute. I’d like to imagine God was looking out for me on that day, but that’s absurd. Why wasn’t God looking out for all those children abused by Catholic clergy like Father Daly?

To be blunt, I am thoroughly disgusted by the moral cowardice of the archdiocese in confronting fully its painful legacy of failing to protect vulnerable children against predatory priests like Father Daly. Shame on the Church.

The Bible says that all sins may be forgiven except those against the Holy Spirit. This is supposed to refer to a stubborn form of blasphemy. Yet I truly can’t think of a worse sin committed by the Church than to allow innocent children to suffer at the hands of predators disguised as “fathers.”

I sincerely hope you are doing something to change the Church, to reform it, to save it. I fear the Church has not fully confessed its sins, and in that sense it truly does not deserve absolution from the laity. Far too often, the Church has placed its own survival ahead of Truth, ahead of Christ as the Way and the Truth, and thus the Church has washed its hands of its crimes, as Pontius Pilate did.

I am staggered by this betrayal.

Perhaps you have truly fought to reform the Church. If you have not yet done so, perhaps you will soon find the moral courage. I pass no judgment on you. Judge not, lest you be judged. But I do find the Church to be wanting.

Recalling scripture, if the Church does not abide in Christ, should it not be cast into the fire and be consumed?

I am sorry to share such a bleak message with you. I find the Church’s decline to be truly tragic because we need high moral standards now more than ever. Yet the Church is adrift, consumed by petty concerns and obedience to power. Just one example: The U.S. Church cannot even clearly condemn the moral depravity of genocidal nuclear weapons!

I realize I am seriously out of step with today’s Catholic church. I believe priests should be able to marry if they so choose. I believe women who have a calling should be ordained as priests. I believe the Church’s position on abortion is absolutist and wrong. More than anything, I believe the Church is too concerned with itself and its own survival and therefore is alienated from the true spirit of Christ, a spirit of compassion and love.

Unlike you, I cannot in good conscience claim to be “devotedly yours in Christ.” But I am sincere in wishing you the moral courage you will need to manifest your devotion in directions that will help the least of those among us the most. For I well recall the song we sang in our youth: Whatsoever you do for the least of my brothers, that you do unto Me.

Sincerely yours

*****

I’m happy to say I get a thoughtful response from a local bishop, who assured me the Church was serious about reform, was doing all that it could to eliminate pedophilia and to punish those who were guilty of it, and that therefore the Church no longer needed outside policing.

It was the last statement that puzzled me. The Church disgraced itself precisely because it had swept decades of crimes under the rug. Hadn’t the Church learned that earnest attempts at reform by insiders were necessary but not sufficient?

So I wrote back these comments to the bishop:

I will say this as well: I don’t think the Church can police itself from within. That’s what produced the scandals to begin with. It’s like asking the Pentagon to police itself, or police forces with their “internal affairs” departments.

The Church has to open itself to being accountable to the laity, not just to reformers like yourself. Thus the Church has to cede power and a certain measure of autonomy, and institutions are loath to do this, for obvious reasons. Meanwhile, the Church is being weakened by lawsuits, as people seek compensation (and perhaps a measure of vengeance) for sins of the past.

Skeptics would reply that it took a huge scandal with major financial implications to force the Church to do the right thing.

For too long, the Church tolerated these crimes. The Church is hardly unique here. Think of sexual assaults within the military (notably during basic training), or think of the Sandusky scandal at Penn State, where Joe Paterno clearly knew of (some) of Sandusky’s abuse, yet chose not to take adequate action. (I was at Penn College when that scandal broke.)

The challenge, as you know, is that the Church is supposed to be a role model, an exemplar of virtue. Priests hold a special place of trust within communities and are therefore held in especially high regard.

As my older brother-in-law explained to me, if a young boy or girl accused a priest of assault in the 1950s or 1960s, few if any people would have believed them. Indeed, the youngster was likely to be slapped by a parent for defaming a priest. That moral authority, that respect, was earned by so many priests who had done the right thing, set the right example. It was ruined by a minority of priests who became predators and a Church hierarchy that largely looked the other way, swept it under the rug, or otherwise failed to act quickly and decisively.

As you say, the Church has learned. It is now better at policing itself. The shame of it all is that it took so much suffering by innocents, and the revelations of the same and the moral outrage that followed, to get the Church to change.

*****

Friends of mine who are still firm believers tell me, correctly, that the Church is much more than the hierarchy. It certainly shouldn’t be defined by the grievous sins of a few. Still, I can’t bring myself to rejoin a Church that so grievously failed the most innocent among us.

There’s a passage in the New Testament where Christ says: “Suffer little children to come unto me.” As in, let the children come, I will bless them, for they in their innocence and humility are examples to us all. He didn’t teach, let the children suffer, molest them and exploit them, then cover it all up.

I still have respect for priests who exhibit the true fruits of their calling. I still find the teachings of Christ to be foundational to my moral outlook. But I find the Church itself to be unnecessary to the practice of my faith, such as it is. I do hope the Church truly embraces transparency and service; I hope it recalls as well its need to preach life and love and peace, as we need these now more than ever.