Serving In (or Thinking About) the U.S. Military for 40 Years

Below is my latest article for TomDispatch.com. Why do I write these articles? I started in 2007, this is 2025, and after 112 articles, nearly all of them calling for America to walk a far less militaristic path, militarism and authoritarianism continue to sink their roots deeper into our culture. Talk about fighting a losing war!

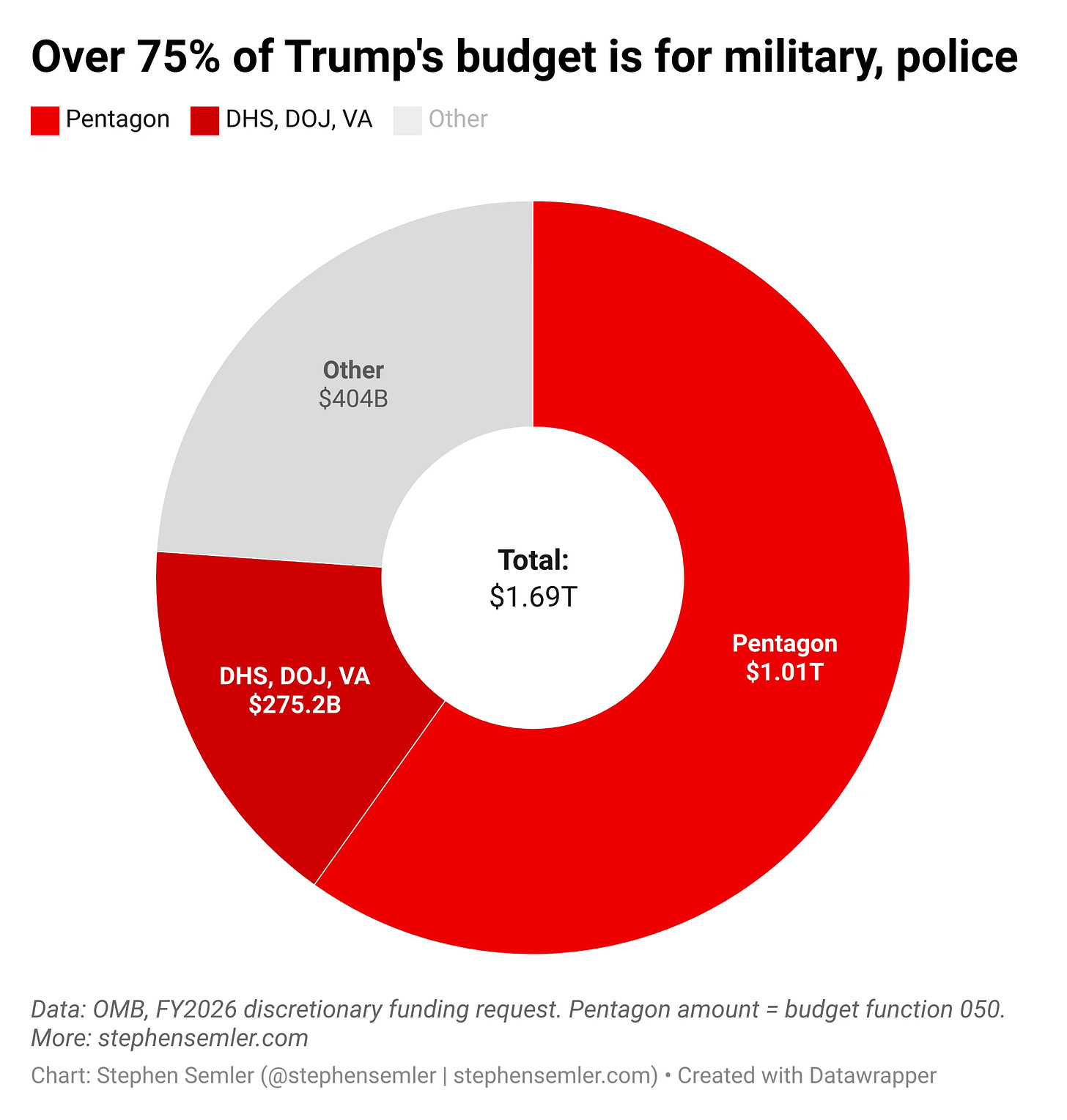

I suppose I write them to preserve my sanity—they’re my effort to make sense of what’s happening around me. But I also write them in the hope that my words might matter, that they might, just might, make a small difference, shifting America away from incessant warfare and colossal military spending. I haven’t given up hope, even as military budgets soar to a trillion dollars and above.

Speaking of which: Here’s an eye-opening chart from Stephen Semler on Trump’s FY2026 budget for America. Sure seems like we’re the Empire in “Star Wars,” doesn’t it?

Anyway, here’s my latest article for TomDispatch:

Forty years ago this month, I was commissioned a second lieutenant in the U.S. Air Force. I would be part of America’s all-volunteer force (AVF) for 20 years, hitting my marks and retiring as a lieutenant colonel in 2005. In my two decades of service, I met a lot of fine and dedicated officers, enlisted members, and civilians. I worked with the Army, Navy, and Marine Corps as well, and met officers and cadets from countries like Great Britain, Germany, Pakistan, Poland, and Saudi Arabia. I managed not to get shot at or kill anyone. Strangely enough, in other words, my military service was peaceful.

Don’t get me wrong: I was a card-carrying member of America’s military-industrial complex. I’m under no illusions about what a military exists for, nor should you be. As an historian, having read military history for 50 years of my life and having taught it as well at the Air Force Academy and the Naval Postgraduate School, I know something of what war is all about, even if I haven’t experienced the chaos, the mayhem, the violence, or the atrocity of war directly.

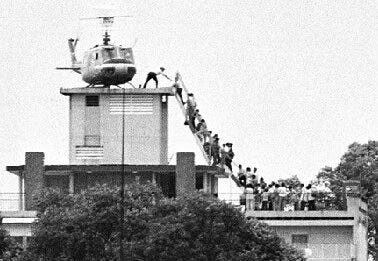

Military service is about being prepared to kill. I was neither a trigger-puller nor a bomb-dropper. Nonetheless, I was part of a service that paradoxically preaches peace through superior firepower. The U.S. military and, of course, our government leaders, have had a misplaced — indeed, irrational — faith in the power of bullets and bombs to solve or resolve the most intractable of problems. Vietnam is going communist in 1965? Bomb it to hell and back. Afghanistan supports terrorism in 2001? Bomb it wildly. Iraq has weapons of mass destruction in 2003? Bomb it, too (even though it had no WMD). The Houthis in Yemen have the temerity to protest and strike out in relation to Israel’s atrocities in Gaza in 2025? Bomb them to hell and back.

Sadly, “bomb it” is this country’s go-to option, the one that’s always on the table, the one our leaders often reach for first. America’s “best and brightest,” whether in the Vietnam era or now, have a powerful yen for destruction or, as the saying went in that long-gone era, “It became necessary to destroy the town to save it.” Judging them by their acts, our leaders indeed have long appeared to believe that all too many villages, towns, cities, and countries needed to be destroyed in order to save them.

My own Orwellian turn of phrase for such mania is: destruction is construction. In this country, an all-too-offensive military is sold as a defensive one, hence, of course, the rebranding of the Department of War as the Department of Defense. An imperial military is sold as so many freedom-fighters and -bringers. We have the mega-weapons and the urge to dominate of Darth Vader and yet, miraculously enough, we continue to believe that we’re Luke Skywalker.

This is just one of the many paradoxes and contradictions contained within the U.S. military and indeed my own life. Perhaps they’re worth teasing out and exploring, as I reminisce about being commissioned at the ripe old age of 22 in 1985 — a long time ago in a country far, far away.

The Evil Empire

When I went on active duty in 1985, the country that constituted the Evil Empire on this planet wasn’t in doubt. As President Ronald Reagan said then, it was the Soviet Union — authoritarian, militaristic, domineering, and decidedly untrustworthy. Forty years later, who, exactly, is the evil empire? Is it Vladimir Putin’s Russia with its invasion of Ukraine three years ago? The Biden administration surely thought so; the Trump administration isn’t so sure. Speaking of Trump (and how can I not?), isn’t it correct to say that the U.S. is increasingly authoritarian, domineering, militaristic, and decidedly untrustworthy? Which country has roughly 800 military bases globally? Which country’s leader openly boasts of trillion-dollar war budgets and dreams of the annexation of Canada and Greenland? It’s not Russia, of course, nor is it China.

Back when I first put on a uniform, there was thankfully no Department of Homeland Security, even as the Reagan administration began to trust (but verify!) the Soviets in negotiations to reduce our mutual nuclear stockpiles. Interestingly, 1985 witnessed an aging Republican president, Reagan, working with his Soviet peer, even as he dreamed of creating a “space shield” (SDI, the strategic defense initiative) to protect America from nuclear attack. In 2025, we have an aging Republican president, Donald Trump, negotiating with Putin even as he floats the idea of a “Golden Dome” to shield America from nukes. (Republicans in Congress already seek $27 billion for that “dome,” so that “golden” moniker is weirdly appropriate and, given the history of cost overruns on American weaponry, you know that would be just the starting point of its soaring projected cost.)

When the Soviet Union collapsed in 1991, fears of a third world war that would lead to a nuclear exchange (as caught in books of the time like Tom Clancy’s popular novel Red Storm Rising) abated. And for a brief shining moment, the U.S. military reigned supreme globally, pulverizing the junior varsity mirror image of the Soviet military in Iraq with Desert Storm in 1991. We had kicked the Vietnam Syndrome once and for all, President George H.W. Bush exulted. It was high time for some genuine peace dividends, or so it seemed.

The real problem was that that seemingly instantaneous success against Saddam Hussein’s much-overrated Iraqi military reignited the real Vietnam Syndrome, which was Washington’s overconfidence in military force as the way to secure dominance, while allegedly strengthening democracy not just here in America but globally. Hubris led to the expansion of NATO to Russia’s borders; hubris led to unipolar dreams of total dominance everywhere; hubris meant that America could somehow have the most moral as well as lethal military in the world; hubris meant that one need never concern oneself about potential blowback from allying with Osama bin Laden in Afghanistan or the risk of provoking Russian aggression as NATO floated Ukraine and Georgia as future members of an alliance designed to keep Russia down.

It was the end of history (so it was said) and American-style democracy had prevailed.

Even so, militarily, this country did anything but demobilize. Under President Bill Clinton in the 1990s, there was some budgetary trimming, but military Keynesianism remained a thing, as did the military-industrial-congressional complex. Clinton managed a rare balanced budget due to domestic spending cuts and welfare reform; his cuts to military spending, however, were modest indeed. Tragically, under him, America would not become “a normal country in normal times,” as former U.N. Ambassador Jeanne Kirkpatrick once dreamed. It would remain an empire — and an increasingly hungry one at that.

In that vein, senior civilians like Secretary of State Madeleine Albright began to wonder why this country had such a superb military if we weren’t prepared to use it to boss others around. Never mind concerns about the constitutionality of employing U.S. troops in conflicts without a congressional declaration of war. (How unnecessary! How old-fashioned!) It was time to unapologetically rule the world.

The calamitous events of 9/11 changed nothing except the impetus to punish those who’d challenged our illusions. Those same events also changed everything as America’s leaders decided it was then the moment to double down on empire, to become even more authoritarian (the Patriot Act, torture, and the like), to go openly to “the dark side,” to lash out in the only way they knew how — more bombing (Afghanistan, Iraq), followed by invasions and “surges” — then, wash, rinse, repeat.

So, had we really beaten the Vietnam Syndrome in the triumphant year of 1991? Of course not. A decade later, after 9/11, we met the enemy, and once again it was our unrepresentative government spoiling for war, no matter how ill-conceived and ill-advised — because war pays, because war is “presidential,” because America’s leaders believe that the true “power of its example” is example after example of its power, especially bombs bursting in air.

The “All-Volunteer” Force Isn’t What It Seems

Speaking as a veteran and a military historian, I believe America’s all-volunteer force has lost its way. Today’s military members — unlike those of the “greatest generation” of World War II fame — are no longer citizen-soldiers. Today’s “volunteers” have surrendered to the rhetoric of being “warriors” and “warfighters.” They take their identity from fighting wars or preparing for the same, putting aside their oath to support and defend the Constitution. They forget (or were never taught) that they must be citizens first, soldiers second. They have, in truth, come to embrace a warrior mystique that is far more consistent with authoritarian regimes. They’ve come to think of themselves — proudly so — as a breed apart.

Far too often in this America, an affinitive patriotism has been replaced by a rabid nationalism. Consider that Christocentric “America First” ideals are now openly promoted by the civilian commander-in-chief, no matter that they remain antithetical to the Constitution and corrosive to democracy. The new “affirmative action” openly affirms faith in Christ and trust in Trump (leavened with lots of bombs and missiles against nonbelievers).

Citizen-soldiers of my father’s generation, by way of contrast, thought for themselves. They chafed against military authority, confronting it when it seemed foolish, wasteful, or unlawful. They largely demobilized themselves in the aftermath of World War II. But warriors don’t think. They follow orders. They drop bombs on target. They make the war machine run on time.

Americans, when they’re not overwhelmed by their efforts to simply make ends meet, have largely washed their hands of whatever that warrior-military does in their name. They know little about wars fought supposedly to protect them and care even less. Why should they care? They’re not asked to weigh in. They’re not even asked to sacrifice (other than to pay taxes and keep their mouths shut).

Too many people in America, it seems to me, are now playing a perilous game of make-believe. We make-believe that America’s wars are authorized when they clearly are not. For example, who, other than Donald Trump (and Joe Biden before him), gave the U.S. military the right to bomb Yemen?

We make-believe all our troops are volunteers. We make-believe we care about those “volunteers.” Sometimes, some of us even make-believe we care about those wars being waged in places and countries most Americans would be hard-pressed to find on a map. How confident are you that all too many Americans could even point to the right hemisphere to find Syria or Yemen or past war zones like Vietnam, Afghanistan, and Iraq?

War isn’t even that good at teaching Americans geography anymore!

What Is To Be Done?

If you accept that there’s a kernel of truth to what I’ve written so far, and that there’s definitely something wrong that should be fixed, the question remains: What is to be done?

Some concrete actions immediately demand our attention.

*Any ongoing wars, including “overseas contingency operations” and the like, must be stopped immediately unless Congress formally issues a declaration of war as required by the Constitution. No more nonsense about MOOTW, or “military operations other than war.” There is war or there is peace. Period. Want to bomb Yemen? First, declare war on Yemen through Congress.

*Wars, assuming they are supported by Congressional declarations, must be paid for with taxes raised above all from those Americans who benefit most handsomely from fighting them. There shall be no deficit spending for war.

*Americans are used to “sin” taxes for purchases like tobacco and alcohol. So, isn’t it time for a new “sin” tax related to profiteering from war, especially by the corporations that make the distinctly overpriced weaponry without which such wars couldn’t be waged?

To end wars and weaken militarism in America, we must render it unprofitable. As long as powerful forces continue to profit so handsomely from going to war — even as “volunteer” troops are told to aspire to be “warriors,” born and trained to kill — this violent madness in America will persist, if not expand.

Look, the 22-year-old version of me thought he knew who the evil empire was. He thought he was one of the good guys. He thought his country and his military stood for something worthy, even for “greatness” of a sort. Sure, he was naïve. Perhaps he was just another wet-behind-the-ears factotum of empire. But he took his oath to the Constitution seriously and looked to a brighter day when that military would serve only as a deterrent in a world largely at peace.

The soon-to-be-62-year-old me is no longer so naïve and, these days, none too sure who’s evil and who isn’t. He knows his country is on the wrong path, that the bloody path of bullets and bombs (and profiting from the same) is always perilous for any freedom-loving people to travel on.

Somehow, America needs to be put back on the freedom trail that inspires and empowers citizens rather than wannabe warriors brandishing weapons galore. Somehow, we need to aspire again to be a nation of laws. (Can we agree that due process is better than no process?) Somehow, we need to dream of being a nation where right makes might, one that knows that destruction is not construction, one that exchanges bullets and bombs for ballots and beauty.

How else are we to become America the Beautiful?

Copyright 2025 William J. Astore