W.J. Astore

And reflecting on notes I made in the margins forty years ago

In college, I majored in mechanical engineering but also took courses in U.S. history and philosophy. I kept most of my college textbooks for a couple of decades, books on statics, dynamics, strength of materials, fluid mechanics and dynamics, thermodynamics, heat transfer, vibrations, along with calculus, physics, chemistry, and the like. But there came a time when these books seemed not only obsolete but a burden of sorts, so I brought them to various used bookstores for trade.

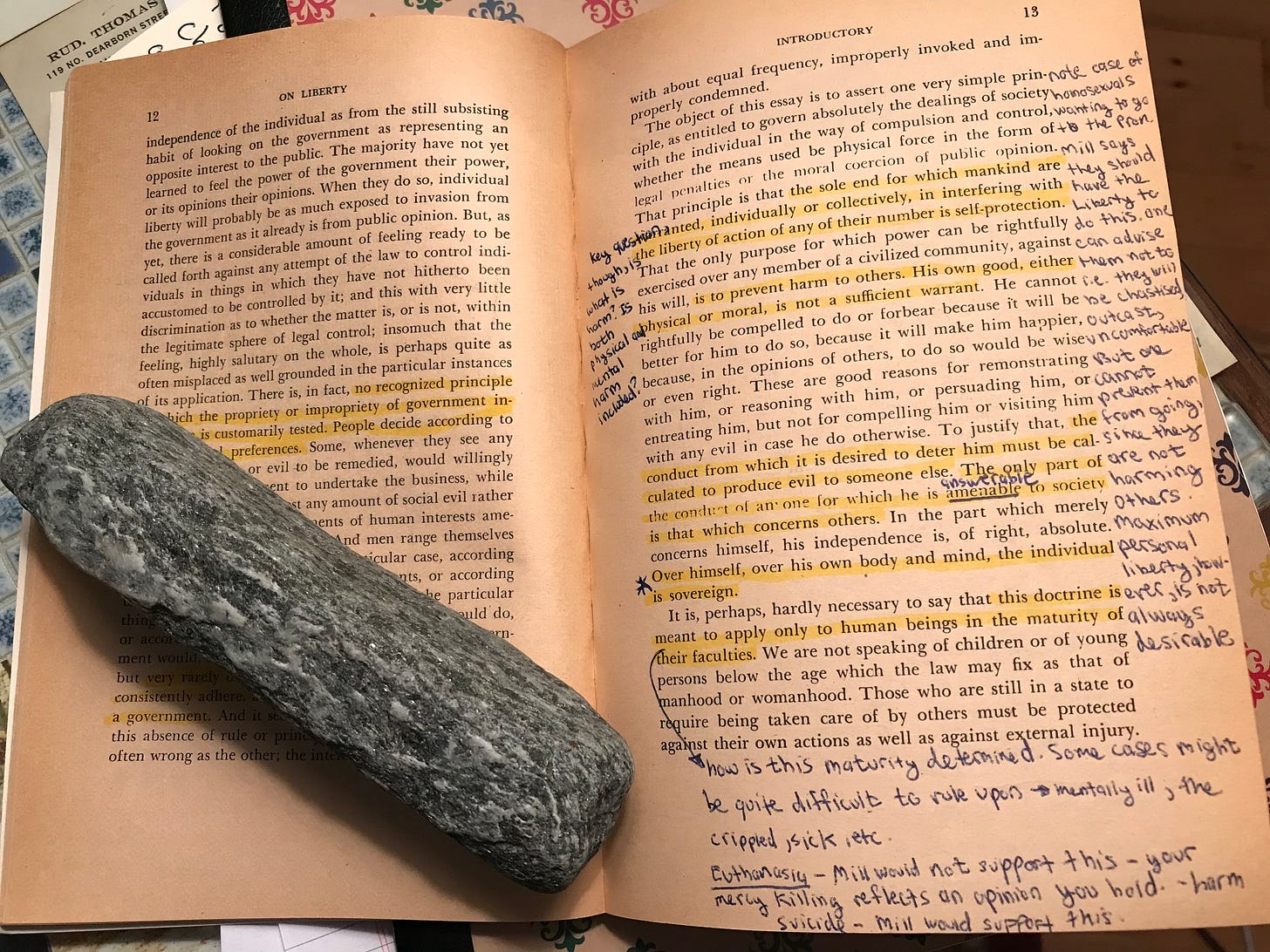

One book I didn’t trade in was a slim volume: John Stuart Mill’s “On Liberty.” It cost me the princely sum of $5.75 in 1983, and I read it for a course in political philosophy. The theme of liberty seemed timeless to me, always pertinent and worth pondering, so I kept the book.

Yesterday, I was shifting some books around and spied my copy among my small collection on philosophy. I opened it and came across a long passage I wrote in the margins back when I first read it in college in 1983. This “marginalia” struck me as a somewhat interesting window into America in 1983 and what I was thinking about as I tried to apply Mill’s insights to American culture.

My marginal comment came as Mill discussed liberty and when people are warranted “in interfering with the liberty of action of any of their number.” Self-protection, Mill wrote, was the only purpose sufficiently compelling here to exercise power to abridge liberty. Preventing harm. It’s insufficient and wrong, Mill added, to act to abridge someone’s liberty because you think it would be better for them, wiser for them, as well as being better for society at large. If the person isn’t harming others, if their actions aren’t “calculated to produce evil to someone else,” those actions shouldn’t be interfered with.

Now, here’s the example that popped into my head back in 1983, which I wrote in the margin:

Note [the] case of homosexuals wanting to go to the prom. Mill says they should have the liberty to do this. One can advise them not to [go], i.e. they will be chastised, outcast, uncomfortable. But one cannot prevent them from going, since they are not harming others.

Back in 1983, before LGBTQ+, in the era of the Reagan revolution in which real men didn’t eat quiche, the idea of homosexuals taking same-sex (or non-binary) dates to the high school prom was more than controversial. It must have been “in the news” for that example to have popped into my head.

It’s interesting how times have changed in forty years. Personal liberty for the LGBTQ+ communities is, I think, far less restricted by the “tyranny of the majority” than it used to be. We have Pride month, Pride celebrations, rainbow flags, and the like. I assume it’s now unremarkable when LGBTQ+ members attend proms with same-sex (or non-binary) dates. And that reflects greater diversity and tolerance within our society along with more liberty, which John Stuart Mill would applaud.

Mill’s message is a good one. We should strive as a society and culture to maximize personal liberty. We should be very careful indeed in exercising power to abridge liberty, especially in the cause of “helping” the other person. As Mill writes, quite powerfully, “Over himself, over his own body and mind, the individual is sovereign.”

Which, to put it in non-gendered language: Over themselves, over their own bodies and minds, individuals are sovereign.

Sometimes, old college textbooks are worth keeping around.

Readers, is there an old high school or college textbook you’ve never parted with, and why?