W.J. Astore

Speaking Truth to Power Isn’t Enough

I was reading R.F. Kuang’s fine novel, Babel, or the Necessity of Violence, and came across this passage:

Power did not lie in the tip of a pen. Power did not work against its own interests. Power could only be brought to heel by acts of defiance it could not ignore. With brute, unflinching force. With violence. (p. 432)

It’s hard to disagree with that, especially within imperial settings in countries dominated by rich and powerful interests. Kuang’s novel is set in the British Empire during the 1830s and 1840s, as Britain was ramping up its first opium war against China. Her quote readily applies to the U.S. empire today and its various global wars of dominance.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the so-called Capitol Insurrection on January 6th and the heavy-handed response to it, especially the long-term prison sentences being handed out. Too much attention is being paid to punishing Trump’s so-called coup supporters and not enough to how Washington, D.C., is increasingly fortifying itself against potential protests. Recall, for example, those Democrats who said they wanted to “defund” the police even as they voted for an expansion of the Capitol police force.

As my wife and I watched the January 6th “coup,” we both had the same thought: What if those protesters hadn’t been so misguided? What if they were truly protesting and “breaching” the Capitol for meaningful change? What if they had been advocating for universal health care, higher wages, an end to expensive and unnecessary wars? Would they ever had gained access to the Capitol? Would members of the Capitol police have moved the barricades, or posed for selfies, with the protesters? I highly doubt it.

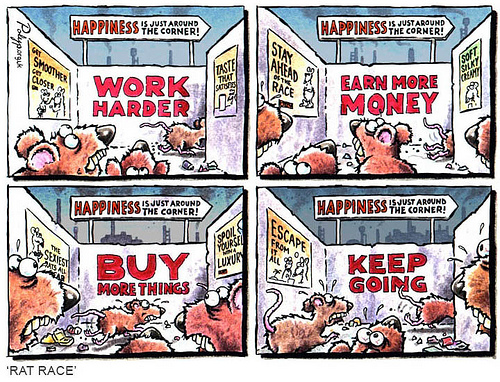

America today has a rigged political system that is thoroughly captured by the moneyed interests. You don’t change that by speaking truth to power because the powerful already know the truth. Indeed, they create the truth. The golden rule is that he who has the gold makes the rules. And that’s what America means when it talks about a rules-based order. The wealthiest, most powerful, nations and people have the gold, want to keep and expand it, so they make the rules with that goal in mind.

How to effect meaningful change in a rigged system without violence is one of the huge questions of our age or any age. In her novel, Kuang suggests that powerful interests only respond to the demands of the less powerful when they are forced to “by acts of defiance” they can’t ignore. She may well be right.

The problem, of course, is that violence that drives change doesn’t always make things better. The French Revolution produced a Reign of Terror followed by the Napoleonic Wars. The Russian Revolution produced Lenin, Stalin, gulags, and ruthless five-year plans. Here I recall an Alexander Solzhenitsyn quote: “All revolutions unleash the most elemental barbarism.”

Yet, if America’s so-called elites continue to close all legitimate avenues to meaningful change, they may be making elemental barbarism inevitable. And I’m not sure they care, in the sense they believe they will always come out on top, that they will, in a word, win, because the masses can always be manipulated or bullied into compliance.