I need to get smart on this

With an ongoing genocide in Gaza and a dangerous war between Russia and Ukraine, who has the time to look to Africa? As we said when I was still in the military, I need to get smart on this.

Coverage of America’s military adventurism/fiascos in Africa is difficult to come by. Fortunately, there’s Nick Turse at The Intercept, whose latest article is entitled:

PENTAGON: U.S. COUNTERTERRORISM EFFORTS HAVE FAILED AFRICANS

A new Pentagon report sheds light on AFRICOM’s disastrous counterterrorism campaigns.

I know Nick Turse from his days at TomDispatch, so I sent him this note in response to his article:

Bombing worked so well to win the war in Indochina — so why not bomb in Africa?

It seems like the goal is permanent war — you throw gasoline on it with all the weapons exports and drone strikes. And they work — war continues.

I guess that’s my obvious take — pay no attention to their words, watch instead what they do. It’s just war and more war. Given that AFRICOM is a military command, should we be surprised that the “solutions” are always violent ones?

That seems to be the U.S. “strategy” in Africa: bomb the “terrorists” while exporting more weapons related to military “assistance” (the building of indigenous African forces ostensibly allied to the U.S.). Again, it’s a strategy that worked so well in Indochina in the early 1960s …

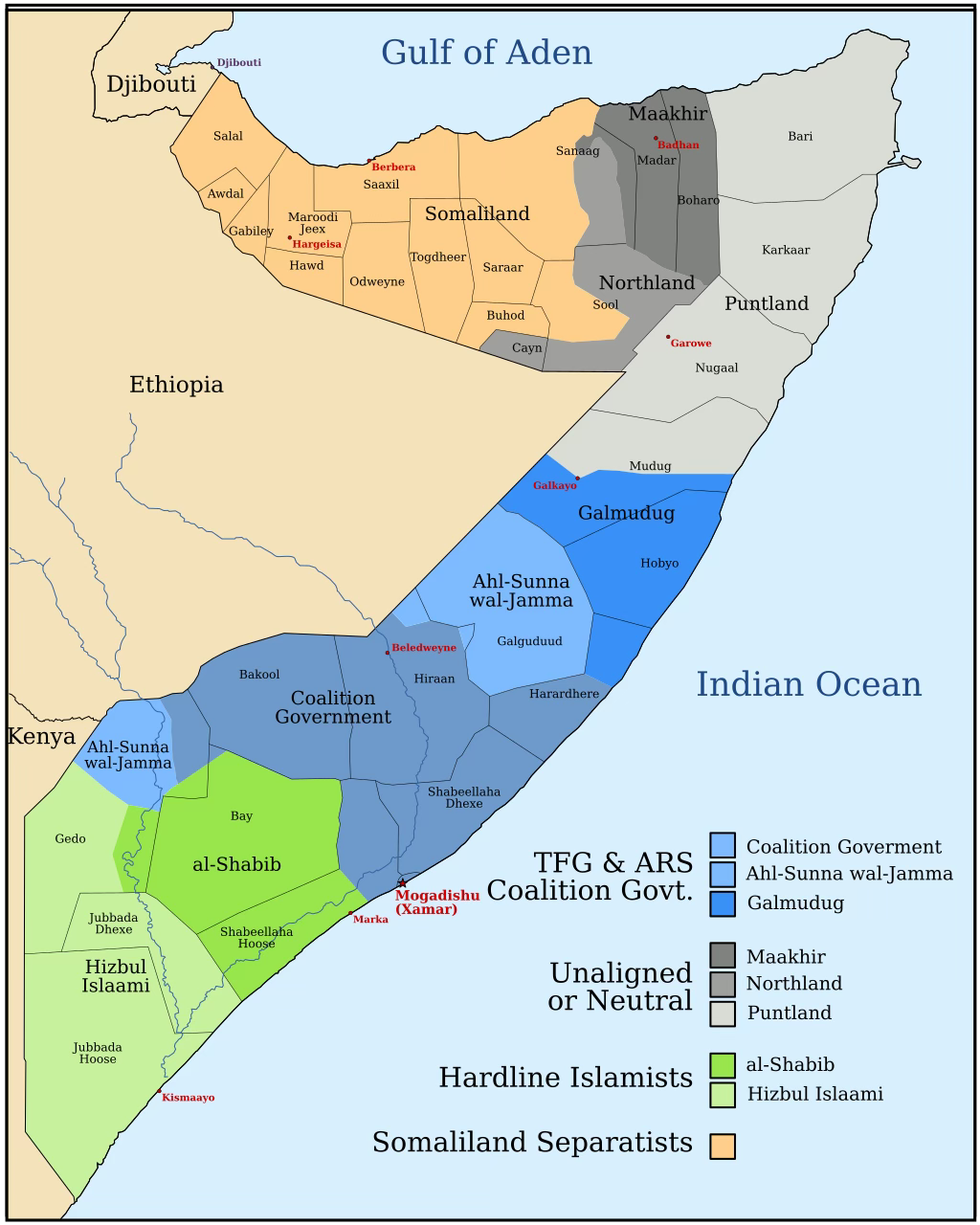

Besides the perpetuation of war there, I don’t know what the U.S. government is up to in Africa. The mainstream media rarely discusses it. I assume control of scarce resources is a major goal. Also, the military-first AFRICOM approach to the area ensures higher profits for and more power to the military-industrial complex. Geographically, the Horn of Africa is vital to the control of sea and trade routes. Proximity to Yemen, Saudi Arabia, and the Red Sea is obvious.

In short, I’m exposing my own ignorance as a way of encouraging all of us to get a bit smarter about what our government is up to in Africa. According to the Pentagon’s own sponsored report, it’s not going well. Here’s the kicker from Turse’s article:

“Africa has experienced roughly 155,000 militant Islamist group-linked deaths over the past decade,” reads a new report by the Africa Center for Strategic Studies, a Pentagon research institution. “Somalia and the Sahel have now experienced more militant Islamist-related fatalities over the past decade (each over 49,000) than any other region.”

“What many people don’t know is that the United States’ post-9/11 counterterrorism operations actually contributed to and intensified the present-day crisis and surge of violent deaths in the Sahel and Somalia,” Stephanie Savell, director of the Costs of War Project at Brown University, told The Intercept, referencing the frequent targeting of minority ethnic groups by U.S. partners during counterterrorism operations.

The U.S. provided tens of millions of dollars in weapons and training to the governments of countries like Burkina Faso and Niger, which are experiencing the worst spikes in violent deaths today, she said. “In those critical early years, those governments used the infusion of U.S. military funding, weapons, and training to target marginalized groups within their own borders, intensifying the cycle of violence we now see wreaking such a devastating human toll.”

Terrorist groups are also gaining ground at an exponential rate. “The past year has also seen militant Islamists [sic] groups in the Sahel and Somalia expand their hold on territory,” according to the Africa Center. “Across Africa, an estimated 950,000 square kilometers (367,000 square miles) of populated territories are outside government control due to militant Islamist insurgencies. This is equivalent to the size of Tanzania.” And as militant groups have expanded their reach, Africans have paid a grave price: a 60 percent increase in fatalities since 2023, compared with deaths from 2020 to 2022, according to the report.

As Turse notes, U.S. special forces deployed to Somalia soon after 9/11 as part of the global war on terror (or, if you prefer, the global war of terror). More than two decades of U.S. military strikes (and strife) in the area have only made matters worse. Can we as a nation stand for more of this “success”?

I think the U.S. strategy in Africa is to continue on the same course while suppressing the news of our failures there. Our influence in the region, such as it is, is military-driven, i.e. various African leaders want our weapons and money but little else (because we have little else to offer).

So, all our military leaders can boast of in the region is colossal air strikes. Did you know we used 60 tons of bombs to kill 14 militants in Somalia last February? Victory indeed will soon be ours … if you define “victory” as rising profits for the bomb-makers.

Readers, help me out. If any of you are following America’s war in Africa, I welcome your insights.