W.J. Astore

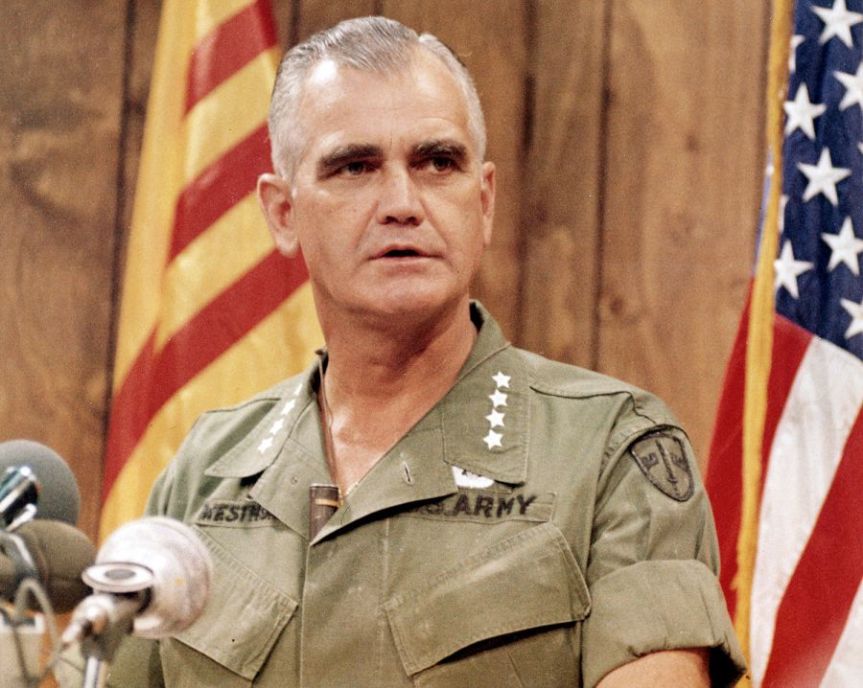

William Westmoreland (“Westy”) looked like a general should, and that was part of the problem. Tall, handsome, square-jawed, he carried himself rigidly; there was no slouching for Westy. A go-getter, a hard-charger, he did everything necessary to get promoted. He was a product of the Army, a product of a system that began at West Point during World War II and ended with four stars and command in Vietnam during the most critical years of that war (1965-68). His unimaginative and mediocre performance in a losing effort said (and says) much about that system.

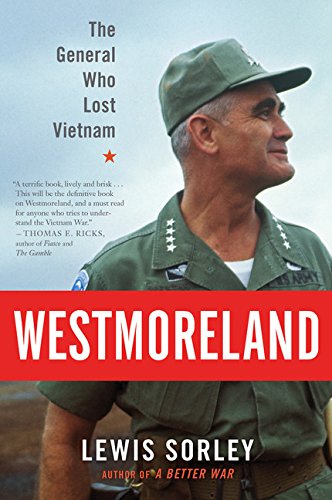

I had these thoughts as I read Lewis Sorley’s devastating biography of Westy, recommended to me by a good friend. (Thanks, Paul!) Before tackling the big stuff about Westy, the Army, and Vietnam, I’d like to focus on little things that stayed with me as I read the book.

- Visiting West Point as the Army’s Chief of Staff, Westy met the new First Captain, the highest-ranking cadet. Westy thought this cadet wasn’t quite tall enough to be First Captain. It made me wonder whether Napoleon might have won Waterloo if he’d been as tall as Westy.

- Westy loved uniforms and awards. Sporting an impressive array of ribbons, badges, devices, and the like, his busy uniform was consistent with his concern for outward show, for image and action over substance and meaning.

- Westy tended to focus on the trivial. He’d visit lower commands and ask junior officers whether the troops were getting their mail (vital for morale, he thought). He’d ask narrow technical questions about mortars versus artillery performance. He was a details man in a position that required a much broader sweep of mind.

- Westy liked to doodle, including drawing the rank of a five-star general. He arguably saw himself as destined to this rank, following in the hallowed steps of Douglas MacArthur, Dwight Eisenhower, and Omar Bradley.

- Westy never attended professional military education (PME), such as the Army War College, and he showed little interest in books. He was incurious and rather proud of it.

Interestingly, Sorley cites another general who argued Westy’s career should have ended as a regimental colonel. Others believed he served adequately as a major general in command of a division. Above this rank, Westy was, some of his fellow officers agreed, out his depth.

Sorley depicts Westy as an unoriginal and conventional thinker for a war that was unconventional and complex. Bewildered by Vietnam, Westy fell back to what he (and the Army) knew best: massive firepower, search and destroy tactics, and made-up metrics like “body count” as measures of “success.” He tried to win a revolutionary war using a strategy of attrition, paying little attention to political dimensions. For example, he shunted the South Vietnamese military (ARVN) to the side while giving them inferior weaponry to boot.

Another personal weakness: Westy didn’t respond well to criticism. When General Douglas Kinnard published his classic study of the Vietnam War, “The War Managers,” which surveyed senior officers who’d served in Vietnam, Westy wanted him to tattle on those officers who’d objected to his pursuit of body count. (Kinnard refused.)

Sorley identifies Westmoreland as the general who lost Vietnam, and there’s truth in that. Deeply flawed, Westy’s strategy was fated to fail. Yet even the most skilled American general may have lost in Vietnam. Consider here the words of President Lyndon B. Johnson in the middle of 1964. He told McGeorge Bundy “It looks to me like we’re getting’ into another Korea…I don’t think it’s worth fightin’ for and I don’t think we can get out. It’s just the biggest damn mess…What the hell is Vietnam worth to me?…What is it worth to this country?” [Quoted in Robert Dallek, “Three New Revelations About LBJ,” The Atlantic, April 1998]

McGeorge Bundy himself, LBJ’s National Security Adviser, said to Defense Secretary Robert McNamara that committing large numbers of U.S. troops to Vietnam was “rash to the point of folly.” In October 1964 his brother William Bundy, then the Assistant Secretary of State for Far Eastern Affairs, said in a confidential memorandum that Vietnam was “A bad colonial heritage of long standing…a nationalist movement taken over by Communism ruling in the other half of an ethnically and historically united country, the Communist side inheriting much the better military force and far more than its share of the talent—these are the facts that dog us today.”

Not worth fighting for, rash to the point of folly: Why did the U.S. go to war in Vietnam when the cause was arguably lost before the troops were committed? Traditional answers include the containment of communism, the domino theory, American overconfidence, and so forth, but perhaps there was a larger purpose to the “folly.”

What was that larger purpose? I recall a “letter to the editor” that I clipped from a newspaper years ago. Echoing a critique made by Noam Chomsky,** this letter argued America’s true strategic aim in Vietnam was to prevent Vietnam’s independent social and economic development; to subjugate and/or subordinate Vietnam and its resources to the whims of Western corporations and investors. Winning on the battlefield was less important than winning in the global marketplace. Vietnam would send a loud signal to other countries that, if you tried to chart your own course independent of American interests, you’d end up like Vietnam, a battlefield, a wasteland.

For sure, Westy lost on the battlefield. But did U.S. economic interests triumph globally due to his punishment of Vietnam and the intimidation it established? How compelling, how coercive, were such interests? Think of Venezuela today as it attempts to chart an independent course. Think of U.S. interest in subordinating Venezuela and its reserves of oil to the agendas of Western investors and corporations. There are trillions of dollars to be made here, not just from oil, but by preserving the strength of the petrodollar. (The U.S. dollar’s value is propped up by global oil sales done in dollars, as vouchsafed by leading oil producers like Saudi Arabia. Venezuela has acted against the petrodollar standard.)

Westy was the wrong man for Vietnam, but he was also a fall guy for a doomed war. He and the U.S. military did succeed, however, in visiting a level of destruction on that country that sent a message to those who contemplated resisting Western economic demands. Westy may have been a lousy general, but perhaps he was the perfect message boy for economic interests that prospered more by destruction and intimidation than by traditional victory of arms.

**For Chomsky, America didn’t accidentally or inadvertently or ham-fistedly destroy the Vietnamese village to save it; the village was destroyed precisely to destroy it, thereby strengthening capitalism and U.S. economic hegemony throughout the developing world. As General Smedley Butler said, sometimes generals are economic hit men, even when they don’t know it.

As a general rule, it’s a lot easier in U.S. politics to sell a war as containing or defeating communist aggression (or radical Islamic terrorism in the case of Iran, or ruthless dictators in the cases of Iraq and Libya) than it is for economic interests and the profits of powerful multinational corporations. For the average grunt, “Remember Exxon-Mobil!” isn’t much of a battle-cry.

Good stuff, I read “Truman” A Chock Block sized book for a Jet, and I always loved Truman’s immortal words for Firing another Poor renegade General “MacArthur” rem. the picture with MacArthur & Our Father & Uncles in his Classic Framed Portrait he kept in the Cellar? Well anyhow Truman said ” I fired him because he wouldn’t respect the authority of the President. I didn’t fire him because he was a dumb son of a bitch, although he was, but that’s not against the law, for Generals. If it was, half to three- quarters of them would be in jail.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another point: If the Vietnam war was an exercise in coercive intimidation through destruction, intended to set a global example, it was also undeniably an exercise in military consumption. The amount of weaponry, ordnance, materiel, just plain bombs and bullets, expended by the U.S. in Vietnam was gargantuan. That consumption, if nothing else, kept the military-industrial complex humming along at top speed. Widow-makers and profit-takers.

LikeLike

I agree with the consumption theory. We’ve destroyed Raqqa, Kobani, ancient stone villages in Afghanistan, abetted/underwritten the same in Yemen. A good case to be made that all this is really just to keep the cash floodgates open at home. So, I agree that beyond the obvious economic interests in places like Venezuela when they get out of line, it appears that simply keeping the domestic complex running was also its own rationale. Who, after all, was intimidated?

LikeLike

I have just finished reading H R McMaster’s book ‘Dereliction of Duty: Lyndon Johnson, Robert McNamara, the Joint Chiefs of Staff and the Lies that Led to Vietnam’. It was published in 1997 and it covers the period from 1961 to 1965. At the time, McMaster had available to him a wide range of meeting records, memos, correspondence etc from the various dramatis personae. The book shows how those people were controlled by their historical experiences, their short-term objectives, and their relationships amongst themselves – and others. Central is LBJ, with his early objective to get re-elected, and then by his Great Society legislation. He relies very heavily on McNamara, who is conditioned by having achieved a resolution to the Cuba crisis by political means and develops a theory that wars can be won or objectives achieved through graduated pressure, in which the armed forces are in reserve. The JCS are rarely involved in decision-making and do not serve their own interests by being unable to agree amongst themselves what they should be doing. Overall, the whole thing lacks any strategic or long-term planning.

LikeLike

please excuse me for not reading either book, but as i understand it, McNamera’s strategy was attempting to keep ww3 from starting. perhaps what i remember and have learned over time is not accurate ?

the hated RMN decided after his landslide to go linebacker 2. McNamera would not have risked it. i may be wrong but, was the next big issue table shapes in paris, or had that already been agreed ?

evidently the parisians have more issues than woodworking these days.

ps after seeing RSM talking in “ The Fog of War “ , i would humbly take exception to your description that he was “ conditioned “ by the cuban missile crises. it would seem he had been there in one of the rooms where the countdown was on. likely his mind was intensely focused. likely he was within spittin’ distance, or closer, to the abyss.

LikeLike

Yes, my rather sloppy wording re McNamara and Cuba. Also, I somehow got my comment split in half (see below-but-one), which didn’t help.

McNamara was one of the inside people on the team that got the Cuban missiles stood down. And it was done without sending any troops to Cuba – ships to the cordon sanitaire, yes, but no troops – and no bombs. That was what formed McNamara’s approach to the Vietnam question. The military could be used, but only as a shadow, in the background. with negotiation in the foreground. As the shadow increasingly did not work, then glimpses of US military could be revealed. This was ‘graduated pressure’.

America misjudged in Korea and brought the Chinese yellow hordes down upon its flanks. And Korea was still very fresh in the mind (though not as fresh as Cuba). Now, the Chinese had nuclear weapons and were potentially much more dangerous. The last thing that McNamara wanted to do was to push the envelope so far in Vietnam that he would engage the military attention of the Chinese. That would have been WW III. How far could he go? He didn’t know and he probably erred on the side of caution. LBJ thought McNamara was the greatest and concurred with his recommendations, whilst McNamara gave LBJ what he wanted – low-level, deniable activities in Vietnam in the period leading up to the 1964 elections, and lowish level after that as LBJ worked on getting resources into his Great Society program.

Once Westmoreland took over in Vietnam, he was always howling for more: he was a military man with a hammer and every problem looked like a nail.

What I have written in response to Bill’s article here, and to you, Old Geezer, is mainly gleaned from my reading of McMaster’s book, though as a long-running resident of SE Asia, I have been a student of the whys and wherefores of the American War (a.k.a. the Vietnam War) since my first visit in 1971.

LikeLike

Yes. These are good points. Westy went for escalation and “the win.” He always, always, wanted more troops. Somehow we went from “training and advising” ARVN to toppling the Diem government to using air power to bring pressure (Rolling Thunder) to sending more than half a million ground troops to wage and win the war ourselves, all in the span of 3-5 years.

Certainly, American arrogance played a role here. We just couldn’t imagine losing. Nor could we imagine a people as tough as the Vietnamese, willing to endure napalm, defoliants, and high explosive just to expel yet another foreign invader.

And that’s part of it too: Americans didn’t see themselves as foreign invaders. We saw ourselves as the good guys. Why don’t they love us?

LikeLike

All good points.

I firmly believe that JFK really did understand what was involved. He visited N Vietnam in 1951, and he saw the problems that the French were having in countering the guerrilla Viet Minh. Three years later, he saw the outcome of that struggle at Dien Bien Phu.

When Eisenhower met with him on 19th January 1961, and suggested that he would have to take troops into Laos to drive back the Pathet Lao, Kennedy knew that would be a hopeless task. He went the diplomatic route and sent Averell Harriman to Geneva to renegotiate the 1954 Geneva Accords and get Laos made neutral. The sole purpose of that was to close down the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

When that didn’t work, and Khrushchev declined the invitation to use his influence with Ho Chi Minh to close the Trail, Kennedy knew that the cause was lost. S Vietnam could never be saved from the communist north – and the communist south!

Westy was the inheritor of the storm of Kennedy’s assassination.

LikeLike

“Yellow hordes “? With racist attitudes like yours, Americans will always be fighting wars. Just recently, a war strategist wrote that for the first time, the United States is in a contest against “a non-Caucssian power”. Does it matter if the cat is black or white as long as it can potentially clean your clock?

LikeLike

I don’t really understand your point. I am British, but I am not sure that it matters whether I am from any especial ethnic group, I am still a pacifist. The fact that I recognise people as coming from certain ethnic groups does not make me racist, does it?

LikeLike

Good article as usual!

A few additional reasons for the Vietnam debacle that I’ve seen elsewhere and seem (sadly) more primal are

1.) ‘momentum’ . We were there and it was ‘easier’ to just keep-on-keepin-on

2.) group-think among presidential advisers

3,) venal re-election politics. To me, this rings truest as the main reason for our

prolonged stay. After all, our POTUS is also commander-in-chief, and

JFK, Johnson, or Nixon could have ended our involvement with a stroke

of their pen, but all were more beholden to party-politics than the lives of

US soldiers, and all were racist enough not to mind the slaughter of millions

of Vietnamese.

LikeLike

And Westmoreland? Well, he wass posted out to Saigon, where he was at the very end of the chain. He was fished out, back to Washington or Hawaii, along with Taylor (General, but now ambassador) from time-to-time, to give advice, which was almost always ignored. And that is how things went in SE Asia as the conflict got under way. US Ambassadors to Laos, until Sullivan arrived, were traditionally ignored by State and the Pentagon, and chastised for not conforming to Washington’s orders. Westmoreland was the man on the ground and his recommendations were generally put aside.

This is not to say that I have any sympathy for him and what happened. He was put in an impossible situation that should have never arisen in the first place, and then he was maintained in a limited policy framework that had, as its best outcome, a stalemate or negotiated peace of some sort. Any ‘military’ objective which had ‘victory’ as its outcome was not under discussion in Washington.

Of course, I have not read the biography, the subject of your article! Sorry for two postings – don’t know what happened.

LikeLike

Admittedly, I occasionally over-simplify things. This may come from having heard too many “justifications” of what any partially-sane person would view as incredibly base & venal behavior/actions during my formative years (a tip: I grew up on the far south side of Chicago during The Glory That Was the Daley Years). Of course, Beltway denizens are far more eloquent than Chicago aldermen, but blowing smoke is blowing smoke, no matter how you dress up it up (“Putting lipstick on a pig.”)

That said, some scattered thoughts that popped up in the immediate wake of the present article:

1a. “Americans hate losers.” George C. Scott in “Patton”

1b. Who would want to go down as the first President to lose a war?

2. The Vietnam War took place in the closing years of an era when a war-time economy was still good for all & sundry (growing up in a steel-producing era, I saw the truth of this day after day, year after year).

3. “Each war sets the stage for the next one.” So saith my Uncle John, a.k.a Sgt. Maj. Dale USA (ret., after 40 years spread over the regular Army & reserves).

4. Westmoreland – the perfect cut-out man – arrived on the scene 40 years too soon. He’d fit right in, today: militarily incompetent & festooned with more decorations than any two WW II Soviet generals.

5a. “Keep it simple, stupid.” My pal Dusty Whitaker, to me, in a north central Texas recording studio, 1994.

5b. Greed and the quest for power are motives enough for most any man. How deep do you really need to look?

6. The individuals who have the greatest effect on the shaping of history – politicians & generals – are often the most ignorant of it. Didn’t anyone in Washington remember what happened to the French? Granted, “Remember Dien Bien Phu!” doesn’t have the same ring as “Remember the Alamo!” but still …

More than enough from me on a chilly, overcast morning in The Netherlands.

LikeLike

Thanks for the great comments. As a retired military guy who taught military history, I admit to certain biases and blind spots. When we taught the Vietnam War, we tended to focus on battles, tactics, and the like. We focused on Khe Sanh and Tet, Rolling Thunder and the Linebacker campaigns, the intricacies of People’s War and counterinsurgency, and topics like that.

What we were less qualified to talk about were the wider political and economic dimensions, as well as policy discussions at the highest level. So I agree JFK and LBJ “stood firm” on Vietnam communism in part for domestic political reasons. Can’t seem weak vis-a-vis Nixon and Goldwater! I agree LBJ and McNamara were looking for a political settlement through gradualism when the North Vietnamese were looking for total victory. And I agree the war got swept up in its own escalatory momentum.

The role of the military-industrial complex must always be remembered as well. The war was very good for business. And the Chomsky critique deserves a hearing …

LikeLike

copyright 2011 … and applied to venezuela. he talked to soldiers in the field about their equipment … he was uncurious … a reminder of the corporations. oh the platitudes !

well, i am not in favor of sending my little brother into venezuela to secure the oil rights. should we sit on our hands while any other american hating country does so ? instead, how about getting a picture of the president in front of a cuban building with the iconic image of che in the background. doh ! that’s already been done.

so what is that smarter way of winning a war, by the way ? in your class did you examine the phrase, “ not one dime more “ ?

who lost nam ? it wasn’t the guys who won every battle. the guys who were well supplied by those evil corporations.

the analysis i have never read, ( conflict check, i’m not that well read ) would describe Eric Blair’s thesis of capitalism’s dis advantage in war.

he wrote “ Homage to Catalonia “ using a pen name.

you are quite right, who would kill for exxon mobil ? a populace is more effectively motivated by a socialist government, Blair’s preference at the time. obviously more able to be motivated by a fascsist or communist government. his doubt was capatalist britain had what it took to keep from being overrun by the national socialists.

we are lucky the brits had enough people to design and produce the Merlin, Hurricane and Spitfire. we are are lucky the brits were able to produce the likes of Geoffrey Wellum, “ First Flight “. he wrote that book with the benefit of hindsight. when you realize what Wellum left off his sleeve you begin to realize how lucky we are guys like Galland were ignored.

the final analysis of freedom vs tyranny is how do a free people find the will to resist tyranny ? ( step #1, accurately identify it )

very brave men have to die. hopefully we have more brave men supplied with what they need to kill many more other brave men. as many as necessary, and 50% more to leave no doubt.

if it can’t be done, be sure to get your social ranking sorted correctly.

otherwise you may not be able to buy toilet paper next month.

by the way william, are you going to ever mention how you elaborated on the frankfurt school to your student warriors ? did the syllabus have time to deconstruct post modernists ?

after all we can’t trust our senses, some people are color blind. what else are we missing ?

LikeLike

OG: I never talked about post-modernism or the Frankfurt School to my students. I just wanted them to know the basics of the U.S. Civil War or who we fought against in World War II!

We need a U.S. government that serves the needs of the people, especially the working classes. And I don’t care what you call it.

Seriously ,we’ll never have “socialism” in this country, except in the military. 🙂

LikeLike

i have a few things on the to do list today, but if i may,

to say the US military is socialist is, imho, the least accurate thing i have seen you write. unless what i think of socialism remarkably diverges what you think.

the US military is a number of killing fields beyond socialism.

i concur strongly that the US government should act on behalf of it’s Citizens. the people , well, your guy bernie wants free healthcare for all who can get here from anywhere. but as we had that conversation already, bernie should just move to cuba, the weather is better than vermont.

if it matters, it would be a pleasure for me to talk to you. here in silli con valley whenever i have had conversations like this, the libs invariably start screaming at me. sometimes it happens pretty soon. so i just stopped saying anything to them. as i say more and more these days, i’m getting to old for that. i wonder if it is me or if things are really getting much more serious these days.

here’s to slowly typing on an ipad at internet length

cheers,

old geezer

LikeLike

OG: Socialism and the military was a joke — sort of. In the military, I got “socialized” housing (based on my rank) and socialized health care (not always great). The government provided for most of my needs for “free” (I only had to sign a contract for a specified number of years; that, and do what I’m told). 🙂

LikeLike

butsudanbill, I am also a South Side area Da Region – Chicago type. I worked at Wisconsin Steel Works from 1966-71, with a time out for 21 or so months in the US Army draftee type). I am sure the draft boards found the South Side a fertile ground for plenty of draftees. >> As a side bar a great book about the Daley Machine is: Don’t Make No Waves…Don’t Back No Losers: An Insiders’ Analysis of the Daley Machine

by Milton L. Rakove

I was sent to Vietnam as a combat infantry type and assigned to the 1st Calvary Division. At the time we were up around the Cambodian border, then we were sent into invade Cambodia. Even as a lowly E-3, I knew we could not “win” the war. Our assignment was to screen the border region to prevent large scale NVA infiltration, the ARVN were supposed to defend the populated areas.

The ARVN simply did not have the manpower, and expertise in terms of maintenance of the equipment our type of modern mobile war required. There was also the endemic corruption in South Vietnam. The ARVN’s invasion of Laos proved they simply did not have the ability to project power.

Westy was simply the wrong man, in the wrong time and in the wrong place. I doubt if any American General in history could have changed the out come of the Vietnam War.

The other side had there own controversies. General Tran Van Tra per Wiki:

“In 1982, Trà published Vietnam: A History of the Bulwark B-2 Theatre, Volume Concluding the 30-Years War, which revealed how the Hanoi Politburo had overestimated its own military capabilities and underestimated those of the U.S. and South Vietnam prior to and during the Tet Offensive.

This account offended and embarrassed the leaders of the newly unified Socialist Republic of Vietnam and reportedly only one of the five volumes survived. It ultimately led to his purging from the Politburo. From 1989 to 1992 he was Deputy Chairman of the Vietnam Veterans Association. He lived under something of a house arrest until his death on April 20, 1996.”

==============================================================

LikeLike

I already have a significant library on the subject of America’s Imperial Military Blunders (IMBs) since the end of WWII — of which I experienced more than enough for my own understanding in Southeast Asia — but on this latest trip to the U.S. I had hoped to get a copy of Gareth Porter’s book, Perils of Dominance: Imbalance of Power and the Road to War in Vietnam/I> (2006). I checked Powell’s City of Books here in Portland, Oregon (our current stopping-off point) but they didn’t have a copy. So I had to order it on-line. I haven’t had time to read and digest the book’s contents, but I think the accompanying dust-jacket summation accurately characterizes the essential nature of a bureaucratic military and political establishment blind drunk with destructive power and convinced of their god-like entitlement to murder, maim, and displace millions of otherwise hapless foreign persons — not to mention a few hundred thousand (mostly enlisted) American military personnel — without a whim of conscience or human empathy. I look forward to adding this one to my library:

Perils of Dominance – Imbalance of Power and the Road to War in Vietnam

Gareth Porter, University of California Press, 2006

Perils of Dominance is the first completely new interpretation of how and why the United States went to war in Vietnam. It provides an authoritative challenge to the prevailing explanation that U.S. officials adhered blindly to a Cold War doctrine that loss of Vietnam would cause a “domino effect” leading to communist domination of the area. Gareth Porter presents compelling evidence that U.S. policy decisions on Vietnam from 1954 to mid-1965 were shaped by an overwhelming imbalance of military power favoring the United States over the Soviet Union and China. He demonstrates how the slide into war in Vietnam is relevant to understanding why the United States went to war in Iraq, and why such wars are likely as long as U.S. military power is overwhelmingly dominant in the world.

Challenging conventional wisdom about the origins of the war, Porter argues that the main impetus for military intervention in Vietnam came not from presidents Kennedy and Johnson but from high-ranking national security officials in their administrations who were heavily influenced by U.S. dominance over its Cold War foes [emphasis added]. Porter argues that presidents Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson were all strongly opposed to sending combat forces to Vietnam, but that both Kennedy and Johnson were strongly pressured by their national security advisers to undertake military intervention. Porter reveals for the first time that Kennedy attempted to open a diplomatic track for peace negotiations with North Vietnam in 1962 but was frustrated by bureaucratic resistance. Significantly revising the historical account of a major turning point, Porter describes how Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara deliberately misled Johnson in the Gulf of Tonkin crisis, effectively taking the decision to bomb North Vietnam out of the president’s hands.

Significantly, both Presidents Barack Obama and Donald Trump have similarly had the “deep state” bureaucracy — both civilian and military — blatantly undermine whatever attempts at negotiated agreements or accommodation with Russia and China that they attempted — even falteringly — to begin. US Presidents have not had effective control of the US military or their own civilian foreign policy bureaucracies since 1945. Too much power accumulated in the hands of unaccountable moral midgets utterly unqualified to hold it in reserve rather than squander it lavishly to no national purpose but their own economic and career aggrandizement.

I already knew this long ago as a US Navy E-5 enlisted man, but it helps to have someone like Gareth Porter remind us once again of how corrupt and murderous the government of our own country became seven decades ago and remains today: a Lunatic Leviathan” as I once termed in a poem of the same name.

LikeLike

Mike: In some sense we’re the prisoners of our own illusions — or delusions. Champion of the free world. The U.S. military as freedom fighters and liberators. Stuff like that.

Combine this with greed — my wife likes to say we’re the United States of Greedica — others say we’re the United States of Advertising (or Amnesia) — and you get an intoxicating brew. We advertise we’re noble and good, with benevolent or disinterested motives, but the reality is greed and more greed.

Glad to hear you hit Powell’s Books. I’ve ordered books through the mail from them but have never been to HQ. One of these days …

LikeLike