W.J. Astore

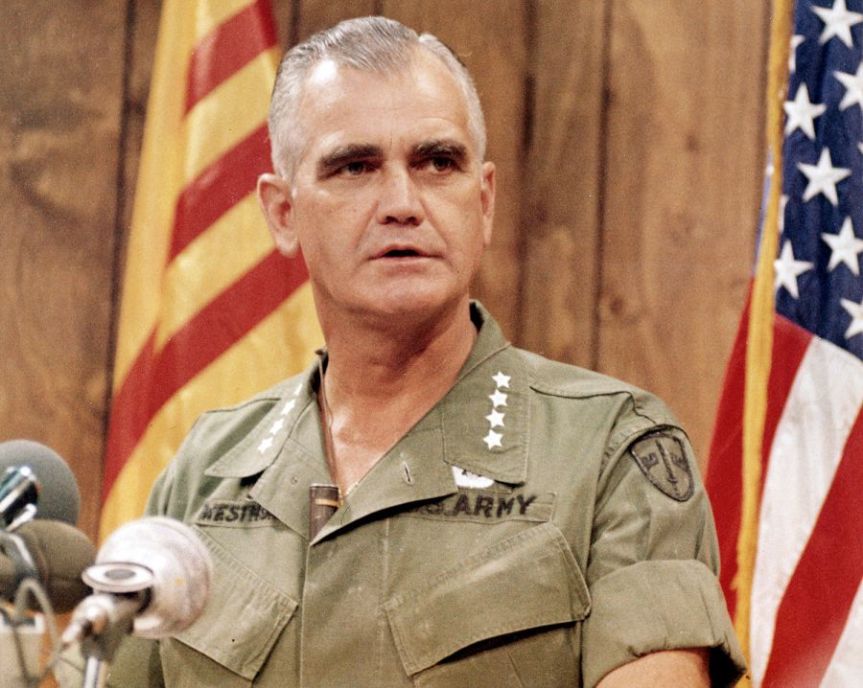

Fear of defeat drives military men to folly. Early in 1968, General William Westmoreland, America’s commanding general in Vietnam, feared that communist forces might overrun U.S. military positions at Khe Sanh. His response, according to recently declassified cables as reported in the New York Times today, was to seek authorization to move nuclear weapons into Vietnam. He planned to use tactical nuclear weapons against concentrations of North Vietnamese Army (NVA) troops. President Lyndon Johnson cancelled Westmoreland’s plans and ordered that discussions about using nuclear weapons be kept secret (i.e. hidden from the American people), which for the last fifty years they have been.

Westmoreland and the U.S. military/government had already been lying to the American people about progress in the war. Khe Sanh as well as the Tet Offensive of 1968 were illustrations that there was no light in sight at the end of the tunnel — no victory loomed by force of arms. Thus the call for nuclear weapons to be deployed to Vietnam, a call that President Johnson wisely refused to countenance.

Westmoreland’s recourse to nuclear weapons would have made a limited war (“limited” for U.S. forces, not for the Vietnamese on the receiving end of U.S. firepower) unlimited. A nuclear attack in Vietnam likely would have been catastrophic to world order, perhaps leading to a much wider war in Asia that could have led to world-ending nuclear exchanges. But Westmoreland seems to have had only Khe Sanh in his sights: only the staving off of defeat in a position that American forces quickly abandoned after they had “won” the battle.

War, as French leader Georges Clemenceau famously said, is too important to be left to generals. Generals often see the battlefield in narrow terms, seeking victory at any price, if only to avoid the stain of defeat.

But what price victory if the world ends as a result?

A subject befitting October 7th, the 17th anniversary of the first US bombs on Afghanistan.

Wouldn’t be surprised if in 50 years time a similar disclosure would appear about some irresponsible general having had similar plans for that country or Iraq. But let me concentrate on a positive example, like the ones William Astore sometimes reminds us of.

A few days ago I participated in the official state burial of a WWII admiral whose father happened to be my great-grand father. He died in 1973 in France and had wanted his ashes to be repatriated, but on two conditions : that Poland would be a sovereign country and that several of his direct subordinates – who sadly had returned after the end of the war and had been jailed, tortured, killed and dumped in a mass grave – would be officially rehabilitated and have an official burial. That finally happened last year, their remains were identified and they were properly buried in the official navy graveyard, next to his own new grave.

That the admiral genuinely cared about his subordinates can also be understood from various other events. As a POW in Germany, whenever his subordinates were moved to a different camp, he insisted on moving with them. This was granted by the Germans, as even they respected him. He was the last one to surrender on October 2nd, 1939 and had done so only to avoid further civilian losses.

Born in 1884 in a distinguished family in Germany, with a German name, as a POW he was offered a high post in Hitler’s army. Not only did he refuse that offer, he even refused to speak German, claiming he ‘forgot that language on September 1st, 1939’.

After the war he refused the rare offer of a British retirement pension, as other Polish combattants from the allied forces were not offered any (one general, with a handicapped daughter, earned a living as a barman in a Scottish nightclub …). In 1948, at the age of 64, he settled in Morocco with his wife and son and for 10 years he worked there to support his family. That work included driving a truck. When 74 years old he settled in a home for Polish combatants & political refugees in France. He no doubt wil also have had his shortcomings, but can be remembered as an example of how a responsible military commander can behave.

LikeLike

I gather from various sources there was consideration to use US air strikes to “save” the French out post at Dien Bien Phu – Operation Vulture. The use of tactical nukes were on the table of options. http://www.airforcemag.com/MagazineArchive/Pages/2004/August%202004/0804dien.aspx

Ike nixed the plan. He later declared, “Airpower might be temporarily beneficial to French morale, but I had no intention of using United States forces in any limited action when the force employed would probably not be decisively effective.”

The political ramifications of a large US Air strike in 1954 would have been enormous, coming less than a decade after the end of WW 2, and not even one year since the Korean Armistice. I feel confident some in Congress would have approved a surgical airstrike or strikes, since their bravery increases in direct proportion from their distance from the battlefield.

When I arrived back in the USA after 13 months in Vietnam 1971, people here simply could not understand why we could not win. The Hawks cursed the politicians for handcuffing the military. If only the Generals could have it their way and invade North Vietnam, then we could achieve victory. These Hawks never considered the potential consequences of a large volunteer force from the People’s Republic of China intervening or the potential for urban warfare in Hanoi.

We had a Kit Carson Scout who went out on patrols with us. He was a NVA defector. He spoke some English. He told me there were many Chinese in North Vietnam, providing assistance.

As usual the architects of war and the politicians escaped any culpability for their lies. The myth had to be created it was a “Tragic Mistake”. The Tragic Mistake theme was a mass pardon, and dispensation. Since it was a Tragic Mistake the High Command could be exonerated and granted immunity.

LikeLike

Yes, ML. “Alternative facts” didn’t begin with Trump. The Rambo movies, for example, advanced the “alternative fact” that the U.S. could and should have won the Vietnam War. Consider Rambo’s speech in “First Blood”:

“But somebody wouldn’t let us win! And I come back to the world and I see all those maggots at the airport, protesting me, spitting. Calling me baby killer and all kinds of vile crap! Who are they to protest me, huh? Who are they? Unless they’ve been me and been there and know what the hell they’re yelling about!”

“Somebody” wouldn’t let us win: the old stab-in-the-back myth. And it’s repeated in the 2nd movie when Rambo asks COL Trautman: “Sir, do we get to win this time?” The implication being “they” will prevent it again: the enemy within.

Not only a “tragic mistake”: For many Americans, an act of treason against our noble troops by the enemy within (the hippies, the politicians, the anti-war types, the liberals, you name it).

Alternative facts — not only a false comfort. Violence against the facts begets violence in real life.

LikeLike

Oh, yes, the spitting. Well, until we get the Rambo movie we didn’t see, and I never heard, of spitting and cursing and so forth. There are NO contemporary accounts available though there are plenty of contemporary accounts of protests, against the US policy, against US leaders and so forth. But in my squadron, which was a TDY squadron (those of us in the field, geodetic surveyors) were constantly traveling to some job or other and usually out in the public, in full view, for weeks or months at a time. If anyone was a “sitting duck” for spitting, vituperation and so forth) it should have been us (I was in from Nov 1968 to 72 – next month will be 50 years since enlistment for me – I got to my squadron in April 1969 and was sent TDY from then to the very end of my four years).

Instead of spitting we were treated with respect and hospitality. Invited to dinners, setup with dates, patted on the back, drinks bought for, invited to discount on Norton motorcyles (in England from the head of Norton who invited us into his house and showed us around as we noticed his motocross pics and trophies from the 1930’s – we didn’t know who he was and only kicked ourselves when we got back to base and looked him up).

And those hippies? There were probably more “hippies” (with short hair) among us than much of the general population where we were. I still remember with fondness my old bell bottoms. Those “protesters” were more concerned for our safety and welfare than the leaders. They were better friends than any of our “leaders” at the time. We didn’t even get cross looks that I remember. We we also small enough as an organization that I think if anyone on any job had gotten hostile responses from the people around a team the rest of us would have heard about it.

The closest anyone in our squadron came to getting in trouble with civilians was one guy on a team working near Utica, NY who flippantly answered some citizen’s question about what the US Air Force was doing (seeing our survey instruments) by telling him that we were building a bombing range in his town. Ha! (Besides we were geodetic surveyors, not land or construction surveyors.) That got back to a congressman who eventually got back to our C.O. who cleared that up. It was kinda funny at the start but when our guy got into (very minor) trouble for it, it turned into LOL funny. We had a great time, really, and that just gave us another one of those entertaining service stories.

As I see it, the only real reason for running the disrespect claims is to shut down any democratic discussion and real evaluation of political policies, especially those involving the military. My advice would be that if the “leaders” have a beef with each other, then put them in a ring and let them fight it out in the ring, themselves, only.

LikeLike

Even as a Vietnamese, I have always been puzzled by the “spitting” myth. Who the hell in their right mind would do that, even if they were against the war? The Soviets didn’t do that after Afghanistan, the German didn’t do that after WWI, and the British didn’t do that after the American Revolution.

That said, compared it to German after WWI seems apt. It felt to me that under Reagan’s terms, just like the Weimar Republic, the myth that “We could’ve won if not for the politicians” was constructed by people with insidious motives.

LikeLike