Richard Sahn

These are not exactly happy times. Americans have fewer safeguards for their jobs, financial well-being, and, ultimately, their very lives. Uncertainty and insecurity have become more prevalent than ever I can remember. As a consequence, insomnia, depression, angst seem to be characteristic of an increasing number of people across the country, almost as American as apple pie. Just as being a divorcee in California is nothing to write home about—you’re even considered odd if you have never been divorced—so is the sense that something “bad” can happen at any time, without warning. Sociologists—I am a sociologist–call this condition “anomie,” a concept formulated by one of the founders of sociology, Emile Durkheim. The Trump presidency, it may be argued, exacerbates anomie since we seem to be moving closer to economic nightmares and possibly nuclear holocaust than in recent decades.

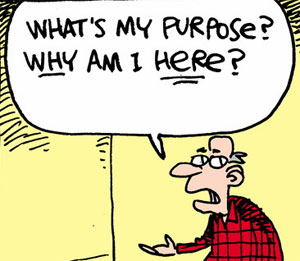

What exactly is anomie? Anomie literally means without norms. It’s a psychological condition, according to Durkheim, in which an individual member of a society, group, community, tribe, fails to see any purpose or meaning to his/her own life or reality in general. Anomie is the psychological equivalent to nihilism. Such a state of mind is often characteristic of adults who are unemployed, unaffiliated with any social organization, unmarried, lack family ties and for whom group and societal norms, values, and beliefs have no stabilizing effect.

The last situation can readily be the outcome of exposure to sociology courses in college, providing the student does not regularly fall asleep in class. I’ve always tried to caution my own students that sociology could be, ironically, dangerous to their mental health because of the emphasis on critical thinking regarding social systems and structures. Overcoming socialization or becoming de-socialized from one’s culture—when one begins to question the value of patriotism, for instance—can be conducive to doubt and cynicism which may give rise to anomie. Of course, I also emphasize the benefits of the sociological enterprise to the student and to society in general. For example, a sociology major is perhaps less likely to participate voluntarily in wars that only favor special interests and which unnecessarily kill civilians.

Clinical depression is virtually an epidemic in the U.S. these days. Undoubtedly, anomie is a major factor, especially in a culture where meaningful jobs or careers are difficult to obtain. To a great extent social status constitutes one’s definition of self. In Western societies the answer to the perennial philosophical question, “Who are you?” is one’s name and then job or role in the social structure. Both motherhood and secure jobs or careers are usually antidotes against anomie. Childless women and unemployed or under-employed males are most susceptible to anomie.

What does postmodernism offer to combat the anomie of modern society and now the Trump era itself? An over-simplification of post-modernism or the postmodern perspective is that there is no fixed or certain reality external to the individual. All paradigms and scientific explanations are social constructs, one model being no more valid than the other. A good example of the application of the postmodern perspective is the popular lecture circuit guru, Byron Katie. Ms. Katie has attracted thousands of followers by proclaiming that our problems in life stem from our thoughts alone. The clutter of consciousness, thoughts, feelings, can simply be recognized as such during meditation and then dismissed as not really being real. Problems gone.

An analogy here is Dorothy Day, the founder of the Catholic worker movement, proclaiming in the 1960s that “our problems stem from our acceptance of this filthy, rotten system.” Postmodernists would claim that our problems stem from our acceptance of the Enlightenment paradigm of reality—the materialist world-view, rationality itself. Reality, postmodernists claim, is simply what we think it is. There is no “IS” there. Postmodern philosophers claim that all experiences of a so-called outside world are only a matter of individual consciousness. Nothing is certain except one’s own immediate experience. The German existential philosopher, Martin Heidegger, contributed significantly to the postmodern perspective with his concept, “dasein,” or “there-being.” Dasein bypasses physiology and anatomy by implying that neurological processes are not involved in any act of perception, that what we call “scientific knowledge” is a form of propaganda, that is, what we are culturally conditioned to accept as real. There is no universal right or wrong, good or bad.

The great advantage of adopting the postmodern perspective as a way of overcoming anomie is the legitimacy or validation it gives to non-ordinary experiences. If the brain and nervous system are social constructs then so-called altered states of consciousness such as near death experience (NDE), out-of-body experience, reincarnation, time-travel, spirits, miraculous healing become plausible. Enlightenment science and rationality are only social constructs, byproducts of manufactured world-views. The “new age” idea that we create our own reality rather than being immersed in it has therapeutic value to those suffering from anomie.

Sociologist Peter Berger employs the concept of “plausibility structures” to legitimize (make respectable) views of the “real world” which conflict with the presuppositions of Enlightenment science. Science then becomes “science” or social constructs which may or may not have validity even though they are widely accepted as such. A good example is the postmodern practice of deconstructing or calling into question empirical science and rational thought itself, disregarding the brain as source of all perceptions, feelings, desires, and ideas. Postmodernists maintain that only individual consciousness is real; the brain is a social construct which doesn’t hold water—no pun intended—as the source of what it means to be human.

CAVEAT

The postmodern perspective may work for a while in suppressing anomie and dealing with the horrors of a hostile or toxic social and political environment. Sooner or later, however, existential reality intervenes. The question is, can postmodernism alleviate physical pain, the death of a loved one, personal injury and illness, the loss of one’s home and livelihood? At this point in the evolution of my philosophical reflections I would argue that postmodernism can reduce or eliminate the depression that inevitably comes from too much anomie–but only temporarily. The postmodern perspective is not up to the task of assuaging the truly catastrophic events in one’s life. As much as I would like not to believe this, I’m afraid only political and social action can help us out when the going really gets rough, although I don’t recommend sacrificing the teaching of critical thinking, a possible cause of anomie, in regard to society’s values and institutions.

Richard Sahn, a professor of sociology in Pennsylvania, is a free-thinker.

To me, postmodernism is too atomistic and esoteric to provide much relief from anomie. Most people, I think, are not going to get much comfort from the idea that their pain and confusion aren’t “real” because reality itself is a construct.

Instead of offering comfort, might postmodernism actually contribute to anomie? Humans have been called the social animal. People crave a sense of belonging, a sense of purpose, a schema in which they can fit themselves and that provides meaning. Postmodernism provides nothing solid, no schema, but perhaps I’m too rational or too stuck in the matrix.

It’s all those years of watching “Star Trek” and admiring the cool rationality of Mr. Spock …

LikeLike

In the movie Star Trek IV, the crew of the Enterprise heads home to Earth from Vulcan in a captured Klingon spacecraft. To help pass the time in transit, Dr McCoy attempts to have a philosophical conversation with Mr Spock, still recovering from his “death” on the Genesis planet in Star Trek II followed by his resurrection and re-education (re-programming) in Star Trek III. Things to not go well — metaphysically speaking — because Mr Spock repeatedly misses the import of Dr McCoy’s idiomatic, metaphorical references.

Mr Spock: “I’m receiving a number of distress calls.”

Dr McCoy: “I don’t doubt it.”

Meanwhile, back on Earth, an alien probe has begun to vaporize the oceans by directing a high energy beam at them, apparently expecting some sort of reply and not getting one.

Federation High Commissioner: “There does not seem to be any way to answer this probe.”

Vulcan Ambassador Sarek (Spock’s father): “It is difficult to answer when one does not understand the question.”

I don’t know. Somehow, the subject of this thread — “postmodernism” (“after” + “modernism”?) and the sociology of aimless boredom — stimulated my addled brain to free-associate, resulting in my receiving a number of distress calls …

LikeLike

Distress Call #1:

“There is no ‘IS’ there.”

Tell that to former U.S. President Bill Clinton who walked straight into a perjury-trap ambush and wound up impeached for “lying” to a grand jury because he couldn’t reconcile the tense aspects of the verbal inflection “is” with the various denotative and connotative aspects of metaphysical “being.” As noted semiotician Umberto Eco would say, “being” has infinite extension and null intension, meaning that it points to everything and says nothing about anything. Even Aristotle couldn’t untangle the self-referential, infinitely recursive semantic gremlin:

“There is a science which investigates being as being and the attributes which belong to this in virtue of its own nature.” — Aristotle, The Metaphysics

By Elizabethan times one philosopher in particular — anticipating the imminent rise of the scientific method — got closer to the nature of the problem of language used about language instead of the real world:

“No one can justly or successfully discover the nature of any one thing in that thing itself, or without numerous experiments which lead to farther inquiries.” — Francis Bacon, The Great Instauration

Someone once said that the typical person thinks about “being” as deeply and as often as a fish thinks about water. Hence, a few thoughts of my own, in verse, naturally:

Ichthyological Metaphysics

When I need a word that rhymes with “fizz,”

A term that brings to mind an empty bubble,

I can always call on good old “is,”

And save myself the slightest bit of trouble.

When I want a noise that sounds like “fuzz,’

To symbolize a meaning I’ve forgotten,

I can do with nothing less than “was,”

Which changes “new” to “old” — from fresh to rotten.

When I need the past for him-and-her

Or the subjunctive mood in doubtful cases,

Postulating that, and if, they “were,”

Joins fact and logic, and them both debases.

When I feel like heading to the bar,

But don’t wish to examine my intention,

I can say my cravings simply “are”:

For lazy drunks, the neatest word-invention.

When I wish to take off on the lam

To dodge the karma earned from lousy choices,

I can vaguely note the way I “am,”

Which tends to silence any nagging voices.

When I want to never look and see,

But jump instead at any mere suggestion,

I can ask: “To ‘be’ or not to ‘be’?”

Avoiding action through this pseudo-question.

When I need to shift from “now” to “then”

Because I’ve screwed the pooch for all to witness,

I can point to how things might have “been,”

And hope this covers up my own unfitness.

When I cannot face the sordid taint

Of life as it confronts the normal peasant,

I – like Tweedledee – say “isn’t” “ain’t.”

Conflating timeless absence with the present.

When I gather these inflections few

Into a “verb” that sums up disagreeing,

I speak bubbles as the others do,

And chalk-up ignorance to magic “being.”

When I swim in school I seldom sink,

But waste my time, like any son or daughter.

I just feed and float and breathe and drink,

While never taking thought about the water.

Michael Murry, “The Misfortune Teller,” Copyright 2009

Yes, I think that encapsulates what history will record as “Clinton’s Conundrum.” It all does depend on the meaning one ascribes to “is,” the universal denotator, in the sense that this relative pronoun (not a “verb” as C. S. Peirce explained) points the attention at “something” while leaving it to the rest of the language to place that something within the remembered experience of the individual organism.

Personally, as a long-time practitioner of E-Prime — English without the ‘is” — I just avoid the damn thing like the proverbial plague, choosing instead to think in terms of actual subjects and verbs — Who? did what? to whom? when? where? how? and why? — in any prose sentences that I write. I know the problem and I know what to do about it.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Grammar Gestapo just nailed me for speaking of the “relative” pronoun (who, whom, which, whoever, whomever, whichever, and that) instead of the “demonstrative” pronoun (like “this” or “that,” “these” or “those”) as the actual functioning of the copula “is,” which simply indicates that what comes before it and what comes after it point to the same object. My bad.

LikeLike

Mike: I tend to avoid thinking too much about being, existence, reality, and similar questions. There’s an old saying, something like “Even the philosopher ducks his head when he walks toward a low beam.” Thinking the low beam doesn’t exist because reality is what you make it to be is hazardous to one’s head and health.

As a writer, I’m already in my own head enough. Perhaps too I lack the patience, intellect, insight, what-have-you, to tackle Heidegger and similar philosophers.

On a different subject, some people have tried to connect/blame postmodernism and deconstructionism for our “post-fact” world, the world of con men like Trump. But this to me is silly; con men have been around forever, and so too have sophists and similar conjurers and mischief-makers.

So when it comes to philosophy, I’ve always enjoyed Plato’s Dialogues and some of Aristotle, and I’ve read people like Francis Bacon, Rene Descartes, Spinoza, Nietzsche, and Kierkegaard. But I’m not sure, really, how much they’ve influenced me. I think the New Testament and Christ’s teachings have been a much bigger influence, in part because I was raised Catholic, but also because there’s a moral vision there that I find compelling and “truthful.”

LikeLike

When I first looked at this blog and glanced at the title, I “read” anime. After reading the blog and trying to digest Anomie and Postmodernism, I turned back to Anime and the WIKI definition: a Japanese-disseminated animation style often characterized by colorful graphics, vibrant characters and fantastical themes.

Without a doubt we have, colorful, vibrant, and repellent Agent Orange for a president. Just four years ago Agent Orange as president would have been a fantastical theme. Is our world really anime?? Could be we are living the Allegory of the Cave and just see the shadows.

From the movie and book The Lathe of Heaven – To let understanding stop at what cannot be understood is a high attainment. Those who cannot do it will be destroyed on the lathe of heaven.

My preference is anime over Anomie and Postmodernism. One of the smartest men I ever I met said, >> And the A-Holes shall inherit the Earth.

LikeLike

Speaking of memorable quotes, I particularly enjoyed a line from the musical “Camelot” where Mordred, the bastard son King Artur and Morgan Le Fey said: “It’s not the earth the meek inherit, it’s the dirt.”

Sure seems that way to me.

LikeLike

Mike: It’s definitely not a time for meekness or weakness in Trump’s America.

LikeLike

Leaving sociology and philosophy aside for the moment, the psychiatrists have their own name for the phenomenon under discussion here: namely, “ennui,” a word borrowed from the French, meaning “A gripping listlessness or melancholia caused by boredom; depression.” I know something of this from personal experience.

Sometime back in early 1971, I found myself languishing for months on end at Solid Anchor, an advanced tactical support base (ATSB) on the banks of a dirty brown salt-water river situated about two kilometers from the southernmost tip of Vietnam. No roads in or out. Access only by boat or aircraft (plane or helicopter). As base interpreter/translator (trained originally as an electrician) I had long periods with nothing much to do except consume inordinate quantities of anything alcoholic that I could get my hands on. One night during a torrential downpour, someone bet me five dollars that I wouldn’t take off all my clothes, put on my steel helmet, march across the compound to the operations center, salute the officer of the watch, and report for duty. I won the five dollars.

Others, higher up in the command food chain did not, of course, find my increasingly psychotic escapades at all amusing. So, the next morning I received a summons from the officer in charge of my section. He put things to me simply, in terms that I could understand: “Murry, you perform an important function at this base and we would find it very difficult to replace you. But you obviously have too much free time on your hands and if you don’t find something worthwhile to do with it, we will have no choice but to send you off for a pschiatric evalution.”

Now, nothing scares the living shit out of a sailor like mention of a “psych evaluation.” Like the old Roach Motel ads on tv: “The roaches check in, but they don’t check out.” Or like the Hotel California, “you can check out any time you like, but you can never leave.”

So I asked for guidance: “What the hell can anyone find to do around an isolated nowhere place like this?”

“Well,” the officer suggested helpfully, “You’re a language guy, so why don’t you take a correspondence course in some other languange, like Japanese, for example.” Just what I need, I thought, another Asian language that I’ll never use once I leave this piece-of-shit excuse for a country. Still, compared to the alternative of spending the rest of my life in a padded cell guarded by sadistic Marine guards, studying Japanese sounded preferable. So I signed up for a course through USAFI and actually earned three units of college credit from the University of Oklahoma. I didn’t realize it at the time, but studying Japanese to stay out of U. S. Military Bedlam changed the course of my life, mostly for the better. But I wouldn’t know that until years later.

Anyway, I know a little, but not much, about philosophy: preferring the Pragmaticism of Charles Sanders Peirce and the General Semantics of Alfred Korzybski, but I do know a great deal about ennui, a very real psychiatric affliction which can lead to any number of bizarre behaviors or addictions, from alcoholism to suicide. I never found Aristotle of any assistance, but I did pick up a book on Japanese once and found the decoding of strange symbols therapeutic enough given my limited intellect and scarce economic resources. It really doesn’t take all that much to remain sane in a crazy world, but it does take something, and the trick lies in finding it. Either that or making it up for oneself.

LikeLike

A helpful officer! A rarity for sure 🙂

LikeLike

Mike: there’s a little scene in “Jackie” that resonated with my wife and me. Jackie O. is struggling to find meaning in her life after the assassination of JFK and she seeks advice from a priest. He doesn’t provide easy answers, saying something like that, “Some days, we just have to get up and make the coffee.” And sometimes that’s the way it is. We just keep going — with a little help from a cup of coffee, our loved ones, and maybe our faith as well.

LikeLike

Great article!

LikeLike