W.J. Astore

“It’s their [South Vietnam’s] war to win. We can help them … but in the final analysis, it’s their people and their government who have to win or lose this struggle.” President Kennedy in September 1963

“We are not about to send American boys nine or ten thousand miles from home [to fight in Vietnam] to do what Asian boys ought to be doing for themselves.” President Johnson in 1964

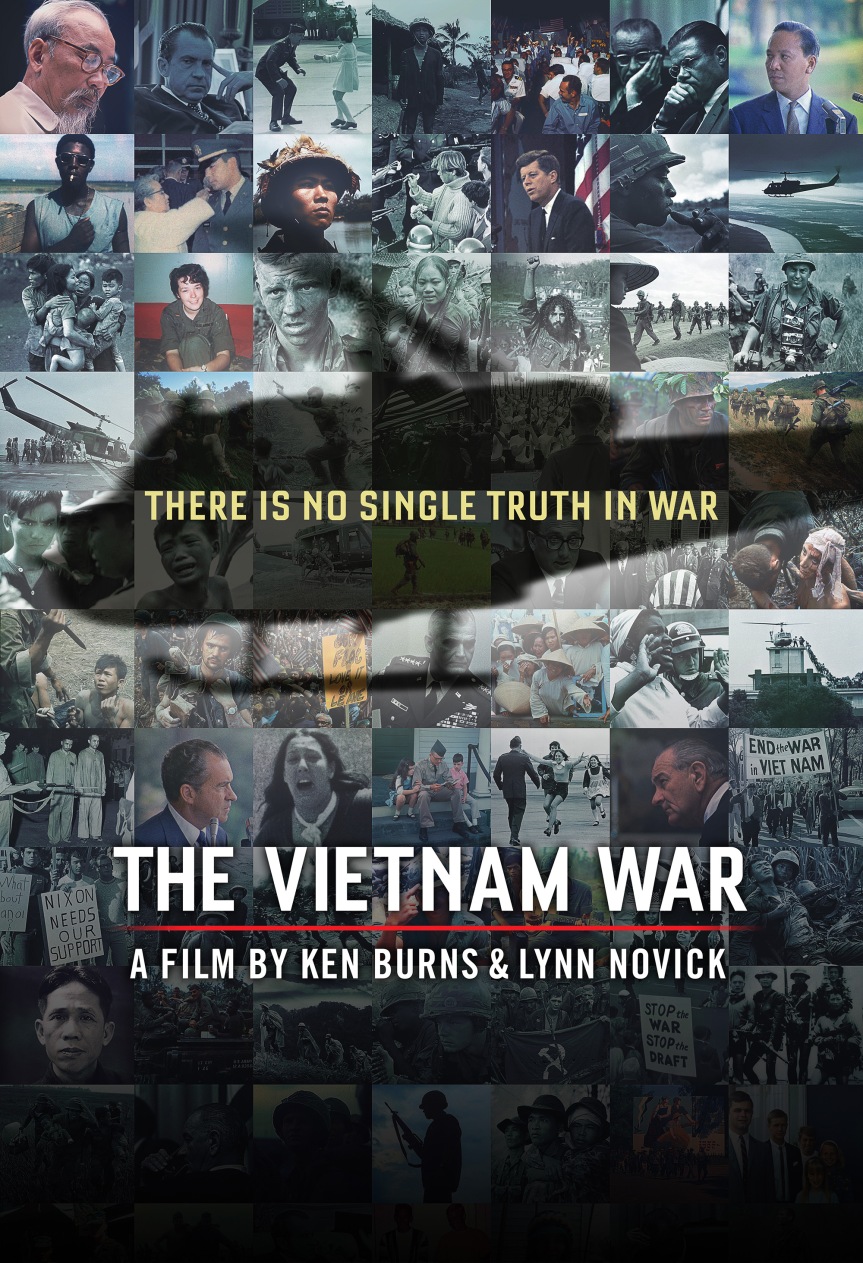

I’ve now watched all ten episodes of the Burns/Novick series on the Vietnam War. I’ve written about it twice already (here and here), and I won’t repeat those arguments. Critical reviews by Nick Turse, Peter Van Buren, Andrew Bacevich, and Thomas Bass are also well worth reading.

I now know the main message of the series: the Vietnam war was an “irredeemable tragedy,” with American suffering being featured in the foreground. The ending is revealing. Feel-good moments of reconciliation between U.S. veterans and their Vietnamese counterparts are juxtaposed with Tim O’Brien reading solemnly from his book on the things American troops carried in Vietnam. The Vietnamese death toll of three million people is briefly mentioned; so too are the bitter legacies of Agent Orange and unexploded ordnance; regional impacts of the war to Laos and Cambodia are briefly examined. But the lion’s share of the emphasis is on the American experience, with the last episode focusing on subjects like PTSD and the controversy surrounding the Vietnam War Memorial in Washington, D.C.

The series is well made and often powerful. Its fault is what’s missing. Little is said about the war being a crime, about the war being immoral and unjust; again, the war is presented as a tragedy, perhaps an avoidable one if only U.S. leaders had been wiser and better informed, or so the series suggests. No apologies are made for the war; indeed, the only apology featured is by an antiwar protester near the end (she’s sorry today for the harsh words she said decades ago to returning veterans).

The lack of apologies for wide-scale killing and wanton destruction, the lack of serious consideration of the war as a crime, as an immoral act, as unjust, reveals a peculiarly American bias about the war, which Burns/Novick only amplify. The series presents atrocities like My Lai as aberrations, even though Neil Sheehan is allowed a quick rejoinder about how, if you include massive civilian casualties from U.S. artillery and bombing strikes, My Lai was not aberrational at all. Not in the sense of killing large numbers of innocent civilians indiscriminately. Such killing was policy; it was routine. Sheehan’s powerful observation is not pursued, however.

What the Burns/Novick series truly needed was a two-hour segment devoted exclusively to the destruction inflicted on Southeast Asia and the suffering of Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian peoples. Such a segment would have been truly eye-opening to Americans. Again, the series does mention napalm, Agent Orange, massive bombing, and the millions of innocents killed by the war. But images of civilian suffering are as fleeting as they are powerful. The emphasis is on getting to know the veterans, especially American ones, of that war. By comparison, the series neglects the profound suffering of Vietnamese, Laotians, and Cambodians.

In short, the series elides the atrocious nature of the war. This is not to say that atrocities aren’t mentioned. My Lai isn’t ignored. But it’s juxtaposed with communist atrocities, such as the massacre of approximately 2500 prisoners after the Battle of Hue during the Tet Offensive, a war crime committed by retreating North Vietnamese Army (NVA) and National Liberation Front (NLF) forces.

Yet in terms of scale and frequency the worst crimes were committed by U.S. forces, again because they relied so heavily on massive firepower and indiscriminate bombing. I’ve written about this before, citing Nick Turse’s book, Kill Anything That Moves, as well as the writings of Bernard Fall, who said that indiscriminate bombing attacks showed the U.S. was not “able to see the Vietnamese as people against whom crimes can be committed. This is the ultimate impersonalization of war.”

Why did many Americans come to kill “anything that moves” in Vietnam? Why, in the words of Fall, did U.S. officialdom fail to see the peoples of Southeast Asia as, well, people? Fellow human beings?

The Burns/Novick series itself provides evidence to tackle this question, as follows:

- At the ground level, U.S. troops couldn’t identify friend from foe, breeding confusion, frustration, and a desire for revenge after units took casualties. It’s said several times in the series that U.S. troops thought they were “chasing ghosts,” “phantoms,” a “shadowy” enemy that almost always had the initiative. In American eyes, it wasn’t a fair fight, so massive firepower became the equalizer for the U.S.—and a means to get even.

- Racism, depersonalization, and alienation. U.S. troops routinely referred to the enemy by various racist names: gooks, dinks, slopes, and so on. (Interestingly, communist forces seem to have referred to Americans as “bandits” or “criminals,” negative terms but not ones dripping with racism.) Many U.S. troops also came to hate the countryside (the “stinky” rice paddies, the alien jungle) as well. Racism, fear, and hatred bred atrocity.

- Body count: U.S. troops were pushed and rewarded for high body counts. A notorious example was U.S. Army Lieutenant General Julian Ewell. The commanding general of the 9th Infantry Division, Ewell became known as the “Butcher of the Delta.” Douglas Kinnard, an American general serving in Vietnam under Ewell, recounted his impressions of him (in “Adventures in Two Worlds: Vietnam General and Vermont Professor”). Ewell, recalled Kinnard, “constantly pressed his units to increase their ‘body count’ of enemy soldiers. This had become a way of measuring the success of a unit since Vietnam was [for the U.S. Army] a war of attrition, not a linear war with an advancing front line. In the 9th [infantry division] he had required all his commanders to carry 3” x 5” cards with body count tallies for their units by date, by week, and by month. Woe unto any commander who did not have a consistently high count.”

The Burns/Novick series covers General Ewell’s “Speedy Express” operation, in which U.S. forces claimed a kill ratio of 45:1 (45 Vietnamese enemy killed for each U.S. soldier lost). The series notes that an Army Inspector General investigation of “Speedy Express” concluded that at least 5000 innocent civilians were included as “enemy” in Ewell’s inflated body count—but no punishment was forthcoming. Indeed, Ewell was promoted.

Ewell was not the only U.S. leader who drove his troops to generate high body counts while punishing those “slackers” who didn’t kill enough of the enemy. Small wonder Vietnam became a breeding ground for atrocity.

- Helicopters. As one soldier put it, a helicopter gave you a god’s eye view of the battlefield. It gave you distance from the enemy, enabling easier kills (If farmers are running, they’re VC, it was assumed, so shoot to kill). Helicopters facilitated a war based on mobility, firepower, and kill ratios, rather than a war based on territorial acquisition and interaction with the people. In short, U.S. troops were often in and out, flitting about the Vietnamese countryside, isolated from the land and the people—while shooting lots and lots of ammo.

- What are we fighting for? For the grunt on the ground, the war made no sense. Bernard Fall noted that, after talking to many Americans in Vietnam, he hadn’t “found anyone who seems to have a clear idea of the end – of the ‘war aims’ – and if the end is not clearly defined, are we justified to use any means to attain it?”

The lack of clear and defensible war aims, aims that could have served to limit atrocities, is vitally important in understanding the Vietnam war. Consider the quotations from Presidents Kennedy and Johnson that lead this article. JFK claimed it wasn’t America’s war to win — it was South Vietnam’s. LBJ claimed he wasn’t going to send U.S. troops to Vietnam to fight; he was going to leave that to Asian boys. Yet JFK committed America to winning in South Vietnam, and LBJ sent more than half a million U.S. “boys” to wage and win that war.

Alienated as they were from the land and its peoples, U.S. troops were also alienated from their own leaders, who committed them to a war that, according to the proclamations of those same leaders, wasn’t theirs to win. They were then rewarded for producing high body counts. And when atrocities followed, massacres such as My Lai, U.S. leaders like Richard Nixon conspired to cover them up.

In short, atrocities were not aberrational. They were driven by the policy; they were a product of a war fought under false pretenses. This is not tragedy. It’s criminal.

Failing to face fully the horrific results of U.S. policy in Southeast Asia is the fatal flaw of the Burns/Novick series. To that I would add one other major flaw*: the failure to investigate war profiteering by the military-industrial complex, which President Eisenhower famously warned the American people about as he left office in 1961. Burns/Novick choose not to discuss which corporations profited from the war, even as they show how the U.S. created a massive “false” economy in Saigon, riven with corruption, crime, and profiteering.

As the U.S. pursued Vietnamization under Nixon, a policy known as “yellowing the bodies” by their French predecessors, the U.S. provided an enormous amount of weaponry to South Vietnam, including tanks, artillery pieces, APCs, and aircraft. Yet, as the series notes in passing, ARVN (the South Vietnamese army) didn’t have enough bullets and artillery shells to use their American-provided weaponry effectively, nor could they fly many of the planes provided by U.S. aid. Who profited from all these weapons deals? Burns/Novick remain silent on this question—and silent on the issue of war profiteering and the business side of war.

The Vietnam War, as Tim O’Brien notes in the series, was “senseless, purposeless, and without direction.” U.S. troops fought and died to take hills that were then quickly abandoned. They died in a war that JKF, Johnson, and Nixon admitted couldn’t be won. They were the losers, but they weren’t the biggest ones. Consider the words of North Vietnamese soldier, Bao Ninh, who says in the series that the real tragedy of the war was that the Vietnamese people killed each other. American intervention aggravated a brutal struggle for independence, one that could have been resolved way back in the 1950s after the French defeat at Dien Bien Phu.

But U.S. leaders chose to intervene, raining destruction on Southeast Asia for another twenty years, leading to a murderous death toll of at least three million. That was and is something more than a tragedy.

*A Note: Another failing of the Burns/Novick series is the lack of critical examination about why the war was fought and for what reasons, i.e. the series takes at face value the Cold War dynamic of falling dominoes, containment, and the like. It doesn’t examine radical critiques, such as Noam Chomsky’s point that the U.S. did achieve its aims in the war, which was the prevention of Vietnamese socialism/communism emerging as a viable and independent model for economic development in the 1950s and 1960s. In other words, a debilitating war that devastated Vietnam delayed by several decades that people’s emergence as an economic rival to the U.S., even as it sent a message to other, smaller, powers that the U.S. would take ruthless action to sustain its economic hegemony across the world. This line of reasoning demanded a hearing in the series, but it’s contrary to the war-as-tragedy narrative adopted by Burns/Novick.

For Chomsky, America didn’t accidentally or inadvertently or ham-fistedly destroy the Vietnamese village to save it; the village was destroyed precisely to destroy it, thereby strengthening capitalism and U.S. economic hegemony throughout the developing world. Accurate or not, this critique deserves consideration.

The death of one man is a tragedy. The death of millions is a statistic. Joseph Stalin-

The millions of Asian deaths as a result of our war machine is treated as a statistic to be quickly glossed over. The enduring legacy of unexploded ordinance and Agent Orange is virtually ignored. The US responsibility for the Cambodian Genocide was not mentioned if I recall.

Maybe I missed it but I do not recall any mention of how Veterans poisoned by Agent Orange had to fight for benefits. I do not recall any Vietnamese suffering from Agent Orange were given center stage.

Several people who were not in Vietnam asked me about the series. As a combat infantry veteran (draftee type 1970/71) I told them it was whitewash. The people responsible for the decision making here in the USA were never called out. Let me be clear – Vietnam was not a mistake in judgement – It was LIEs that got us into Vietnam and LIEs that kept us there!!!!

Ike’s warning about the military-industrial complex was an indication that Corporatism and the Militarists had grabbed America by the throat.

Country Joe and Fish in his Vietnam Song hit all points:

Come on Wall Street, don’t be slow,

Why man, this is war au-go-go

There’s plenty good money to be made

By supplying the Army with the tools of its trade,

But just hope and pray that if they drop the bomb,

They drop it on the Viet Cong.

Well, come on generals, let’s move fast;

Your big chance has come at last.

Now you can go out and get those reds

‘Cause the only good commie is the one that’s dead

And you know that peace can only be won

When we’ve blown ’em all to kingdom come.

========================================

LikeLiked by 2 people

Yes. You’re right about the Burns/Novick series and Agent Orange, unexploded ordnance, and the Cambodian genocide. They’re briefly mentioned — and that is all.

Lies lead to more than tragedy. Lies enable murderous criminality — and serve to cover it up as well.

LikeLike

Excellent – thank you

David King Keller, PhD M: 415-444-6795 E: david@kbdag.com

“Life shrinks or expands in proportion to one’s courage” — Anais Nin

>

LikeLike

Truth in Disclosure: I never “served” in Vietnam due to corruption in the MIC. Yes, if you worked on JP Stevens, supplier of uniforms & tents, etc. advertising account, you were exempt. So was a floor sweeper for Boeing. I don’t have the stomach to watch the series today, but I NEVER marched in an anti-war parade; considered myself lucky. Remained ‘neutral’: good cop-out word!

Time passes. PBS is hardly honest; never was. We spent little there in the 60’s & 70’s – afraid our products would also get trashed – as false. It was never reliable!

Yet this essay by Astore opens up a good forum. Veterans & ‘cop-outs’ alike. The excuse for Vietnam was Commies would steal our Mom’s push button clothes washer & Dad’s Buick. Never happened, even though we lost!

Today’s excuses for war are even more flimsy: “Human Rights! Democracy!” The irony being they’re both disappearing in US, not in our “enemies”. Ike was right! The MIC is the worst to fear.

Can anyone with a sane mind figure out how 2 planes brought down the “World Towers”? With kerosene? A fancy hotel, that took police/hotel security, 72 MINUTES to locate the shooter!?

I am not a “conspiracy theorist”, but perhaps the corruption of Vietnam, no punishment of General’s lying, brought on the HORRORS of today!

Meanwhile, all running (brand!) shoes are made in Vietnam, for the Western world. Mom’s push button washer is now made in Korea, and Dad drives a Lexis.

The HORROR of Vietnam was it was a ‘philosophical’ war, that killed millions of people, including US soldiers. No one was put to blame for the fault to protect French Imperialism in the 1st place!

Middle East today? Give me a Break! All lost! STUPID and learned no lesson from sad, unnecessary,Vietnam.

LikeLiked by 1 person

The Viet Nam War was based on lies and deception.

No different from (all) other wars, really.

LikeLike

There was no mention of the Winter Soldier Investigation which took place in 1973, I believe, and was broadcast on several listener-supported radio stations. The testimony was read into the Congressional Record.

http://www2.iath.virginia.edu/sixties/HTML_docs/Resources/Primary/Winter_Soldier/WS_entry.html

LikeLike

Given the nature of the Vietnam War and of every operation since. I want to ask any/all of you who have been in the service, would you encourage a young person today to join the U.S. military? I cannot see how any of the operations underway anywhere in the world have even the remotest connection with protecting the country and that is the only reason to let loose a tool for destroying lives and material professionally. I know a proud marine, justifiably proud, who was one of the first to hit the beach at Iwo Jima. Today, I cannot conceive of any pride coming from being a part of what our military is doing, all of our soldiers/sailors taking orders from a commander-in-chief who is a professional assassin choosing names of people from a hit list to kill by drone. Can anyone tell me how my thinking is in error?

LikeLike

A fair question. I wouldn’t encourage them. And I’d do my best to tell them about the realities of military service, and the ways our military is being misused.

But the decision to serve is a very personal one, and I still think a person can take pride in serving when one serves to the best of one’s ability.

LikeLike

Thank you for your reply. It brings to mind duty.

There is a wonderful book I read called The Metaphysical Club that follows the lives of four notable people from the 19th century, Oliver Wendell Holmes, William James, Charles Peirce and John Dewey.

Holmes fought for the Union in the Civil War and was wounded three times always to return to duty. He becomes friends with another man, a junior officer, Henry Abbott. Abbott is fearless, defies death under fire so many times without injury that he gets a reputation for invincibility. What drives Abbott is his attitude that anything larger than the specific assignment is not relevant; all that matters is that one do one’s best to achieve the specific goal, even if that goal is pointless or given to one by a fool. Holmes is deeply impressed and is devastated when Abbott is eventually killed in combat.

Holmes does not speak of his wartime experience later in life, nor does he want to talk of the glory of the Union cause couched in terms of good against evil. He becomes dedicated to interpreting the law, eventually on the Supreme Court, removed from passion – what do the words say? Nothing beyond that is important.

Duty. Can a person, as Abbott did, separate it from anything beyond it? Can a person close his/her mind to the larger effect that doing one’s duty accomplishes? Certainly the military would encourage duty above all. Do as one is told and the machine of death and destruction of which you are a part can respond most effectively to command. For the soldier under stress, subject to fear and panic, this simple directive has great appeal. Moreover, in fighting defensively for one’s country, it can easily be justified as the only thing to think about.

But in war where one’s country is not even remotely threatened, this idea of duty enables the death machine for purposes such as power projection, resource control, ideological victory, the expansion of the field for private enterprise. Here, I think of Tolstoy’s book, The Kingdom of God is Within You, not for any theological reason but for his important point that it is only the individual soldier obeying orders without question that any war is possible. Do I do my duty when it allows war that is not necessary?

To the everlasting credit of all who were involved with the anti-war effort during the Vietnam War, not least those who went to Canada and the grunts who refused to fight, they did the right thing. “My country right or wrong” is the same as a blind man saying, “I am going to throw away my cane that allows me to distinguish things and walk where I am told regardless”. It comes to a bad end.

We should think of Old Glory as transparent, allowing us to see through it when it is intentionally placed before our eyes like a blanket blinding us to everything but obedience.

LikeLike

The typical trio is “duty, honor, country.” So, duty to orders is not enough. Honor is important too. And what does “country” mean? For a U.S. service member, it means the ideals described and prescribed in the U.S. Constitution, which we swear (or affirm) “to support and defend.”

Soldiers must not be robots. They have a duty to refuse to obey dishonorable and/or illegal orders. Consider My Lai. You’re ordered to kill innocent civilians by a superior. The bravest soldier is the one who refuses that dishonorable, illegal, and wretched order. He (or she) has a higher duty to do so — and he (or she) is upholding the oath by doing so.

LikeLike

Thank you for a thoughtful critique. I haven’t watched the series myself, but I felt the title was telling. The ‘Vietnam War’ is something that ‘happened’ to Americans. The American War is something the US inflicted on a large share of the people of SE Asia. You’ve confirmed what I felt was a bias built into the series from the beginning.

LikeLike

From a Buddhist mother with a remarkably honorable son, now serving his 6th tour of duty as a leader away from home. He keeps my more progressive leanings honest by offering another point of view with which I must wrestle. Life grants us these counterpoints to deepen our understanding of complexities no one would willingly choose to embrace.

This article is another remarkably clear and well-reasoned piece by WJ Astore which encourages reflection on the parallels of where the US is currently involved, the rationale given for it, and the carnage because of it.

LikeLike

An excellent choice of words, “rationale.” Not the reason for doing something in the first place, but a conscious lie made up beforehand just to get things started, or an excuse invented afterwards to avoid accountability and, where required, the necessary punishment that true justice occasionally administers. Marine Corps General Smedley Butler once said that we have only two acceptable reasons for going to war: to defend our homes or defend the Constitution. In not a single case after World War II has either of these conditions applied, so that none of the pointless and ruinous fighting — I won’t dignify these Presidential/Career Military misadventures by calling them “war” — has had any justifiable reason or purpose. Not surprisingly, no Congress has declared war on another nation state since 1941 because no nation state on planet earth has attacked either American homes or America’s Constitution. The United States has not just “gone abroad in search of monsters to destroy,” as our sixth President, John Quincy Adams, warned us against foolishly doing, but has invented imaginary hobgoblins at home before even setting out to vanquish them on the far side of the globe.

Of course, Smedley Butler only made his remarks after serving for thirty years as an admitted “gangster for capitalism,” probably the best summary description of the U.S. military offered to date by one who ought to know. Today, as for the past seventy-plus years, the U.S. military simply fights — aimlessly and disastrously — for the sake of fighting. The fighting has no “reason” other than to provide a steady stream of outrageous corporate CEO bonuses, stockholder dividends, and the pensions and perquisites of retired senior military officers. This Warfare Welfare and Makework Militarism has secondary beneficiaries, of course, most notablly the hothouse orchids, special snowflakes and privileged peacock pugilists known as United States as “political leaders.” Naturally, the feeding and maintenance of this system of corrupt cronyism requires a death grip on over half the nation’s discretionary budget. As George Orwell wrote in “The Theory and Practice of Oligarcical Collectivism” (the book-within-a-book from 1984):

“The primary aim of modern warfare (in accordance with the principles of doublethink, this aim is simultaneously recognized and not recognized by the directing brains of the Inner Party) is to use up the products of the machine without raising the general standard of living.”

In other words, the entire U.S. miltitary/security monstrosity — which I like to call the Lunatic Leviathan — has only one purpose: to suck the life out of the domestic economy so that the productivity of the people’s labor will not result in the betterment of their station in life which might in due course result in the discarding of America’s useless parasitic economic and political “elites.” Any transparent euphemism designed and deployed to disguise this ugly, fundamental truth properly deserves the label “rationale.” In no way do the usual and time-dishonored obfuscations amount to a reason. Reason has fled the United States, replaced by a deserved and rancid Ridicule. The country now consumes itself, lost in its own vicarious fears and fantasies featuring the celluloid exploits of our vaunted Visigoths vanguishing visions of vultures somewhere, someplace, at some time, until … eventually .. after some “progess” and “fragile gains” … as t. s. elliot wrote of The Hollow Men:

This is how the world ends.

This is how the world ends.

This is how the world ends.

Not with a bang, but a whimper.

Men and women so hollow that you can hear their own bullshit echoing in them even before they start moving their jaws and flapping their lips to begin lying.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Watching the news tonight, I caught a reference to our “warriors” being killed overseas in yet another country Americans can’t find on a map. Warriors — the word is bandied about with no thought whatsoever.

But I suppose that’s what the citizen-soldiers of WW2 have become: warriors and “war fighters.” As much as I complain about the loss of the citizen-soldier ideal, the new terminology accurately captures reality — the reality of endless fighting, a celebration of fighting for its own sake. A cult of the warrior, immersed in violence, with images of violence pervasive throughout our discourse and our media. (I watch a lot of sports, so I’m constantly exposed to commercials for SWAT, Seal Team, various violent video games, and so on.)

These new words — warriors, warfighter, and the like — make plain the new world we inhabit, one dominated by fighting and violence and obedience to “the leader.”

LikeLiked by 1 person

I wish to commend Clif Brown (above) for his mention of The Metaphysical Club, by Louis Menand, a really fine book about some rather remarkable American thinkers of the late-nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. One of my favorite quotes concerns Oliver Wendell Holmes and William James:

“Wendell Holmes attended James’s funeral, but privately he made a point of his lack of sympathy with James’s views. He thought that James had made scientific uncertainty an excuse for believing in the existence of an unseen world. ‘His wishes made him turn down the lights so as to give miracle a chance.”

My other favorite quote from Justice Holmes comes from S. I. Hayakwa’s introductory book on Korzybskian general semantics: Language in Thought and Action. Concerning the argumentative two-valued orientation (You-bad/Me-good, and vice versa), Hayakawa wrote:

“This [binary, either/or mentality] was well stated by Oliver Wendell Holmes in his Autocrat of the Breakfast-Table, in which he speaks of the “hydrostaic paradox of controversy:

‘You know that, if you had a bent tube, one arm of which was of the size of a pipestem, and the other big enough to hold the ocean, water would stand at the same height in one as in the other. Controversy equalizes wise men and fools in the same way — and the fools know it‘.”

Not without reason do the rabid religious reactionaries in America demand that the publlic schools “teach the controversy” as if “Creation Science” or “Intelligent Design” — i.e., religion, or “the lights turned down to give miracle a chance” — and science stand equally opposed as merely two dissenting opinions. Justice Holmes would understand Donald Trump and the rabid base of the Republican party perfectly. The fools know their business and will generate all the controversy necessary to keep sane and rational policy from coming anywhere near the government of the United States.

Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes did indeed live a remarkable and intelligent life.

LikeLike

Well said, Mike.

LikeLike

John Dewey (who studied logic under Charles Sanders Peirce at the Johns Hopkins Graduate School) begins his book Reconstruction in Philosophy (1920) as follows:

“Man differs from the lower animals because he preserves his past experiences. What happened in the past is lived again in memory. About what goes on today hangs a cloud of thoughts concerning similar things undergone in bygone days. With the animals, an experience perishes as it happens, and each new doing or suffering stands alone. But man lives in a world where each occurrance is charged with echoes and reminiscences of what has gone before, where each event is a reminder of other things. Hence he lives not, like the beasts of the fields, in a world of merely physical things but in a world of signs and symbols.”

Whenever I think of this optimistic philosophical observation by John Dewey I immediately associate it with another, more realistic, observation by Sir James George Frazer’s The Golden Bough – A Study of Magic and Religion (1922):

“The very beasts associate the ideas of things that are like each other or that have been found together experience; and they could hardly survive for a day if they ceased to do so. But who attributes to the animals a belief that the phenomena of nature are worked by a multifutede of invisible animals or by one enormous and prodigiously strong animal behind the scenes? It is probably no injustice to the brutes to assume that the honor of devising a theory of this latter sort must be reserved for human reason.”

So, yes, we humans do possess the capacity to produce and use signs and symbols for creative and useful purposes — like scientific discovery or the formulation of sound national policy — but nothing guarantees that we will take advantage of that capability. Rather, by indulging in magical, superstitous thinking divorced from truth and reality (but I repeat myself, as Charles Sanders Peirce would remind me) we build fantastic imaginary sand castles in empty air and then, like the fictional naked emperor boasting of his non-existent new clothes, we expect and demand that others confirm us in our lunatic imaginings. Good thing for the “lower” animals that they possess no such magical imaginations. Had they possessed such a dangerous susceptibility for deranged and demented behavior, evolution would never have produced the “higher” animals like us in the first place.

These various reflections came to me when I read about President Donald Trump’s speech “decertifying” the nuclear non-proliferation agreement with Iran and five other countries as well as his withdrawal of the United States from UNESCO, the United Nations organization devoted to education and the preservation of world historic monuments. What a litany of lies, fantasy, and pure garbage. Not a word of these screeds had the slightest connection to reality. Then I happened to tune in to CNN International for my five minute (my wife will allow no more) daily dose of unadulterated bullshit and whom do I see interviewed but You-Know-Her, the only politician in America who can compete with Donald Trump for unadulterated Voodoo incantations aimed at the infantile or insane.

Sorry, John Dewey, but I think that Sir James George Frazer had it right about the animals. At least we don’t see them pissing their pants and shitting their diapers because their “leaders” had conjured for them some signs and symbols representing imaginary hobgoblins on television screens. Certainly we humans could discern the difference between shit and Shinola, but apparently the American variety have no interest in doing so — and the fools they have for “leaders” know it.

LikeLike

Here is the best essay on Burn’s program that I have come across:

https://www.commondreams.org/views/2017/10/15/does-vietnam-even-matter-any-more-does-ken-burns?

LikeLike

Yes. Very good. His micro/macro analogy and use of the mosaic is telling. Burns/Novick focused on the micro. They obviously decided not to ask the big questions or tackle the big issues exactly because they are damning to America’s elite, the decision makers and the profiteers. And the latter did indeed learn. They learned to get rid of the draft, to muzzle the media, and to convince the people that war criticism is unpatriotic because it’s against “our” troops. Yes, they learned …

LikeLike

I did not see the series so cannot comment, but I wonder whether at its end it considered the lasting effect of the Vietnam war on later US wars – such as the ones in Afghanistan and Iraq – and even on those waged by other countries copy-catting US approaches and rationales, such as Saudi Arabia in Yemen?

For when I read your critical comments (and Nick Turse’s ‘Kill anything that moves’), I recognise much of which as a civilian I observed in Afghanistan, even if not always occuring to the same degree, such as:

– At the ground level, U.S. troops couldn’t identify friend from foe, breeding confusion, frustration, and a desire for revenge after units took casualties.

– Racism, depersonalization, and alienation. U.S. troops routinely referred to the enemy by various racist names: gooks, dinks, slopes, and so on.

– No-one who seems to have a clear idea of the end – of the ‘war aims’ – and if the end is not clearly defined, are we justified to use any means to attain it?”

– A war that is “senseless, purposeless, and without direction.”

– Conspiracies to cover up atrocities, massacres.

– War profiteering by the military-industrial complex.

– A “false” economy, riven with corruption, crime, and profiteering.

– Not enough bullets and artillery shells to use their American-provided weaponry effectively, nor could they fly many of the planes provided by U.S. aid.

I cannot assess the continuation of other features such as body counts, as I do not have intimate knowledge of US/NATO military guidelines. But judging from their self-congratulatory announcements of numbers of ‘eliminated’ ‘taliban fighters / leaders’ (many of which in fact are civilians, who after having been killed unsurprisingly fail to prove their innocence), I suspect that this continues to some degree.

Not to mention the infamous Phoenix programme, which still serves as a basis for various ‘counter-insurgency’ strategies and GWOT excesses.

http://www.mcall.com/opinion/yourview/mc-phoenix-program-vietnam-denton-borhaug-yv-0923-20160922-story.html quote:

“Rejali describes one case, the high-value detainee, Vhuyen Van Tai, who was subjected by CIA operatives to electro-torture, water torture, beatings, stress positions, sleep deprivation and confinement in a freezing refrigerated room for two years.

Rejali characterizes this kind of torture as the “National Security Model” in democracies such as the U.S. Torture of this type surges to the surface because of a perceived national emergency, or because the national security bureaucracy has overwhelmed democratic systems that are put in place for restraint.

We are living in times in which it is more urgent than ever to honestly and accurately represent and remember historical chapters of the U.S. such as the Phoenix Program. How else are we to evaluate and analyze renewed calls for enhanced interrogation and torture in our own time?”

Even US voices critical of present military engagements, tend to focus their arguments for ending them on the US’ own costs (both human and financial), rather than those of the invaded country. Your blog and most of TomDispatch contributors being much appreciated exceptions.

I therefore am curious on which arguments the recent book by anti-war activist Scott Horton https://foolserrand.us/ bases its recommendation to withdraw from Afghanistan (which as such I wholeheartedly support).

Is it just the usual “we already have invested too much in that country while they are not even grateful for our ‘sacrifices’, so why continue”? Or does it also acknowledge the plight of the victimised nation, its reduction to a corrupted narco-state which it was not before – at any rate never to such a dramatic degree – with no prospect whatsoever for any positive change?

To quote one of this book’s reviewers, a US Afghanistan veteran: “I expect Horton’s book to not just explain and interpret a current American war, but to explain and interpret the all too predictable future American wars, and the unavoidable waste and suffering that will accompany them.” Whose ‘waste and suffering’, I wonder?

And when Lawrence Wilkerson comments: “Two presidents and several Congresses have failed, the Pentagon has failed, and the military has failed.”, I wonder what it is, that in his opinion they failed to achieve, what the objective was? Apart of course from revenge for 9/11, the institutionalised version of the “desire for revenge after units took casualties”?

‘America’s longest war’? How about ‘Afghanistan’s – unprovoked – longest war’?

Luckily Grant F. Smith’s comment: “[…] damning indictment of the U.S. invasion and occupation of Afghanistan” suggests that – like Nick Turse’s Vietnam account – this book does pay proper attention to the victim’s suffering.

If you or any of your readers have read it, I’d be interested in your opinion.

LikeLike

I haven’t read Horton’s book. I think it’s a case of “Wherever we go, there we are.” In other words, wherever America makes war, we bring certain aspects of ourselves and our culture. A quick list:

1. Almost total reliance on the military.

2. Almost total reliance on kinetic ops, i.e. violence.

3. Use of “force mulipliers” to limit (American) casualties.

4. A stubborn ignorance of the foreign country we’re in.

5. Once committed, a mindless pursuit of “victory” (the desire not to be labeled a “loser”)

6. Once the war gets ginned up, a desire by war profiteers to keep good times rolling.

7. Despite obvious evidence to the contrary, a strong belief that American troops are always on the side of the angels.

I could go on. As Tom Engelhardt wrote in a piece, we count, they don’t. Our troops matter. Their casualties are reported and mourned. Foreign bodies are just that — foreign bodies.

I recall the current U.S. commanding general referring to Afghanistan as a petri dish in which various terrorist strains swim. And U.S. troops are supposed to be some kind of antibody to eliminate all these “bad” strains. What is obvious is that Americans will never see themselves as part of the problem.

LikeLike

As a canadian I have always been thankful that my government was smart enough to keep us out of that war. Too bad the anzacs had to learn the hard way. It was obvious then, as it it is obvious now, that one major factor in the war was the enormous arrogance of the US government, military and, initially, people. The USA never seems to learn from the experiences of others because of its enormous contempt of those others. Thus the USA did not learn, did not try to learn, from the french experience in Indo-Chine. The same mistakes were made again right down to repeating the blunder of Dien Bien Phu at Khe Sanh – with very nearly the same result.

But what could possibly be learned from the french – cheese eating surrender monkeys? Tell that to the men of Bir Hakeim! Just as at Kasserine americans would not listen to advice from the british who had been fighting in N Africa for two years.

Frankly you people need to get over yourselves and stop believing your own propaganda – nobody else believes it.

LikeLike