W.J. Astore

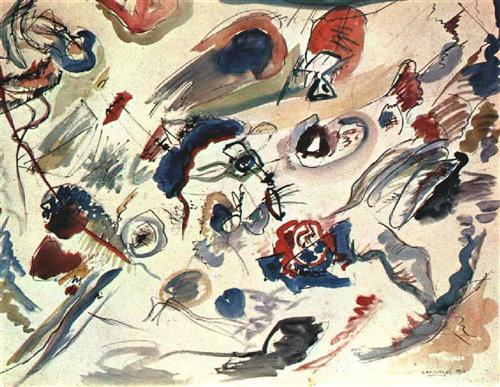

Consider this article a work of speculation; a jumble of ideas thrown at a blank canvas.

A lot of art depicts war scenes, and why not? War is incredibly exciting, dynamic, destructive, and otherwise captivating, if often in a horrific way. But I want to consider war and art in a different manner, in an impressionistic one. War, by its nature, is often spectacle; it is also often chaotic; complex; beyond comprehension. Perhaps art theory, and art styles, have something to teach us about war. Ways of representing it and capturing its meaning as well as its horrors. But also ways of misrepresenting it; of fracturing its meaning. Of manipulating it.

For example, America’s overseas wars today are both abstractions and distractions. They’re also somewhat surreal to most Americans, living as we do in comparative safety and material luxury (when compared to most other peoples of the world). Abstraction and surrealism: two art styles that may say something vital about America’s wars.

If some aspects of America’s wars are surreal and others abstract, if reports of those wars are often impressionistic and often blurred beyond recognition, this points to, I think, the highly stylized representations of war that are submitted for our consideration. What we don’t get very often is realism. Recall how the Bush/Cheney administration forbade photos of flag-draped coffins returning from Iraq and Afghanistan. Think of all the war reporting you’ve seen on U.S. TV and Cable networks, and ask how many times you saw severed American limbs and dead bodies on a battlefield. (On occasion, dead bodies of the enemy are shown, usually briefly and abstractly, with no human backstory.)

Of course, there’s no “real” way to showcase the brutal reality of war, short of bringing a person to the front and having them face fire in combat — a level of “participatory” art that sane people would likely seek to avoid. What we get, as spectators (which is what we’re told to remain in America), is an impression of combat. Here and there, a surreal report. An abstract news clip. Blown up buildings become exercises in neo-Cubism; melted buildings and weapons become Daliesque displays. Severed limbs (of the enemy) are exercises in the grotesque. For the vast majority of Americans, what’s lacking is raw immediacy and gut-wrenching reality.

Again, we are spectators, not participants. And our responses are often as stylized and limited as the representations are. As Rebecca Gordon put it from a different angle at TomDispatch.com, when it comes to America’s wars, are we participating in reality or merely watching reality TV? And why are so many so prone to confuse or conflate the two?

Art, of course, isn’t the only lens through which we can see and interpret America’s wars. Advertising, especially hyperbole, is also quite revealing. Thus the U.S. military has been sold, whether by George W. Bush or Barack Obama, as “the world’s finest military in history” or WFMH, an acronym I just made up, and which should perhaps come with a copyright or trademark symbol after it. It’s classic advertising hyperbole. It’s salesmanship in place of reality.

So, when other peoples beat our WFMH, we should do what Americans do best: sue them for copyright infringement. Our legions of lawyers will most certainly beat their cadres of counsels. After all, under Bush/Cheney, our lawyers tortured logic and the law to support torture itself. Talk about surrealism!

My point (and I think I have one) is that America’s wars are in some sense elaborate productions and representations, at least in the ways in which the government constructs and sells them to the American people. To understand these representations — the ways in which they are both more than real war and less than it — art theory, as well as advertising, may have a lot to teach us.

As I said, this is me throwing ideas at the canvas of my computer screen. Do they make any sense to you? Feel free to pick up your own brush and compose away in the comments section.

P.S. Danger, Will Robinson. I’ve never taken an art theory class or studied advertising closely.

Great post!

Thank you.

LikeLike

I remember one time I started painting an abstract and during the process, I realized I didn’t like it. So, I layered more paint on the canvas. Covered the old paint with new colors. Waited. Added some more color, texture, changed the look, changed the feeling. Waited again. Tried to fix it repeatedly…to make it pleasing. Nothing I could do made me content. It turned into one big mess. It dawned on me that I had lost my purpose of expression somewhere along the way. It got too complicated and untrue. I finally gave myself permission to throw it away. To start over. That moment I became free. Free to clear my head and to decide what it was I was feeling and wanted to communicate… and only then to proceed with the next canvas. The process was easier, more focused. It became a clearer and truer expression of self. It helped me to step back and to re-direct my intention. Perhaps if the painters of our wars were to take a deep breath, step back and start over, they, too, might be able to create a new and truer expression and interpretation of their subject. Oh, they might still be abstract or surreal efforts, but they just might also be a little closer to the truth.

LikeLike

Thanks. Or from their mistakes maybe our war “painters” might learn they shouldn’t paint at all. No talent.

LikeLike

In the first place, art means creation while war means destruction. As far as concerns the United States corporate oligarchy and its vaunted Visigoths (i.e., uniformed “military”) — whom Marine Corps General Smedley Butler called “gangsters for capitalism” — I wouldn’t call anything they do “art.” I wouldn’t even call it “grafitti.” I call it vandalism. And whenever they have a chance to do over what they have already done too many times to even recall, they do exactly the same thing one more time, because after “Plan A” they have no other plan. As Jake Tapper wrote in his book The Outpost:

“It has been said that the United States did not fight a ten-year war in Vietnam; rather that it fought a one-year war ten times in a row. Perhaps the same will one day be said of Afghanistan.”

As a matter of fact, history has already said the same thing about America’s signature Groundhog wars. Sixteen times in Afghanistan alone. And it will say the same thing next year, too. As we used to say in the computer programming business: “When a man makes a mistake, he makes a mistake. But when a machine makes a mistake … makes a mistake … makes a mistake … makes a mistake …” Now, substitute “commits a crime” for “makes a mistake” and you have the mindless corporate war machine that we used to call “America.” Rube Goldberg would recognize the rusting, clanking monster instantly.

On the other hand, someone once said that “All great war photography is anti-war photography.” Which explains why the U.S. military will never allow an independent photographer to show the world graphic images of what our “heroes” have done to other people who have never attacked or harmed the United States. Of course, a few artists have managed to capture the essence of war on canvas, like like Picasso’s “Guernica” which adorns one wall of the United Nations. I remember when former U.S. President George “Deputy Dubya” Bush went before the UN in order to lie and harangue that assembly of nations into supporting his criminal stud-hamster vendetta against the toothless Saddam Hussein of Iraq (he failed). Prior to the speech, someone covered up Picasso’s painting. I figure that either the UN did it so that Dubya’s demented diatribe would not stain the immortal work of art, or that Dubya’s public relations team did it so that the viewing audience wouldn’t see in a single background image a devastating refutation of every drop of bile and vitriol that spewed forth from between the U.S. President’s flapping lips.

I guess I mean to say that, in my opinion, art can critique war, but war can never produce art. Something like that.

LikeLike

Always interesting, Mike. Yes, art is a creative activity, war a destructive one, but in the destructive act, something new is created.

Art can critique war, but art can also celebrate it. So many old classics celebrate “the profession of arms.” Grand canvases celebrated the grandeur of war. In my mind’s eye, I’m picturing the famous painting of the cavalry charge at Waterloo:

LikeLike

WOW! Just discussing with an old friend my experiences in advertising during the 1960’s & ’70’s, supposedly the ‘golden age’ of the dirty business! I worked for ‘full service’ agencies, which means we both bought media & produced creative. There were no discounts, except for heavy usage and we enjoyed a 15.75% mark-up*. I explain such because today there are “Media buying houses”, which might explain today’s ‘fake news’, as they discount heavily. (*This nice profit sometimes subsidized our art depts. Good stuff, but usually over budget.)

We also had far less control of the media’s tangents than they do today: ratings were what mattered. In fact, as the Vietnam War raged, we got a nice surprise via The Pentagon Papers. Though some bosses may scream “Kill the gooks!” inside, readership exploded with their being published, far more than we paid for when the contracts were signed. CBS’s Bill Paley must be praised here: Walter Cronkite’s boss, he wouldn’t budge in his opinions for advertisers.

Flash forward today: I’m shocked such “presstitutes” as CNN seem to be committing suicide financially. In fact, I don’t believe their “profits” figures. Says this old man today, I think the old system was better, both for the media & advertisers. Not to forget readers & viewers! Rotten sales reports & mall closings may prove my point?

LikeLike

As an impressionable youth in the early Sixties I first saw the Famous Civil War Oil Paintings in the City of Brockton, City Hall Rotunda. I was awestruck by all that Glory!. Of the Mass. 54th Infantry led by Col. Shaw and his all black (Colored) Regiment that fought so valiantly at Fort Wagner… If your ever in “The City of Champions” I heartily recommend it. The Art of War a true paradox!.

LikeLike

I well remember those paintings. Quite dramatic. They made you want to be there.

LikeLike

On the National Historic Register as well as Civil War Buffs- well known Sites of Interest!. Always was partial to the Painting of The Unions Monitor vs. the Confederate Merrimac Ironclads Battle…!

LikeLike

This is art created by the VICTIMS of wars who have lived it and are still living it for 30+ years.

https://secure.flickr.com/photos/alienateddotnet/sets/72157612650950462/

LikeLike

I saw these in Toronto some years ago.

http://warrug.com/Info/2008/05/02/canadas-textile-museum-war-rug-show/

LikeLike

Great video, thanks RS :-). Interesting question why these rugs appeared. If I ever manage to get back there, I’ll ask around. Even more interesting considering the fact that most Afghan rugs traditionally have only abstract patterns (even if these have a meaning for whoever knows how to ‘read’ them), even representation of animals usually are not naturalistic but stylised into a pattern. I’ve seen a trend of very expensive ‘western’ style rugs appear in Afghanistan, mostly simple geometric patterns in ‘earth’ colours, in order to please western markets. An expat had them specially woven in Badakhshan.

LikeLike

These rugs in fact are not so much ment to be art as rather a product popular with foreigners – particularly military – and therefore a way to earn a living. If you would carry out a poll among Afghanistan veterans, you’d probably find that many have such a rug at home. Possibly even with their name or regiment woven into it. Same applies to personalised ‘decorative’ wooden boards with metal inlay with similar pictures. So I’d put these rugs (not necessarily those in Toronto, some if which are really beautiful) rather in the advertising category :-).

It’s different with pictures drawn by children, on which an otherwise peaceful valley has tanks added and helicopters flying overhead. They simply draw their daily life as it has been ever since they were born, they never have know anything else. Generally ‘war in art’ is indeed glorifying war and military achievements, defeat is not a marketable subject, even in art.

I’ve come across an interesting phenomenon lately which concerns art & refugees, a similar subject. It seems to me that many artists who use that subject to highlight the plight of refugees, in fact are highlighting their own frustration with being powerless in this matter. The refugees as such are invisible and explanatory text is needed to inform that it is about them.

The worst example of ‘artistic exploitation’ is a young lady who (supposedly with the best intentions to attract attention to the plight of the hungry) planned a ‘starvation cookbook’. I think it eventually never materialised but it was a hype in art circles and she had a presentation during which such ‘dishes’ (boiled leather shoe soles or tree bark flour) were presented as if they were nouvelle cuisine in a posh restaurant. An ‘installation’ about the desperately poor for the blasé art world.

I had been asked to contribute but flatly refused to be involved in what I consider to be trendy exploitation of human misery for one’s own greater glory as an artist, a red line definitely not to be crossed.

Not that expressing one’s frustration in art is bad as such, but for such subjects I prefer art by the war victims (which can include repentent veterans) or refugees themselves. Rather than speak/paint about them and for them, give them an opportunity to speak and express themselves, to share their first hand experience rather than being treated as an object, mostly of pity.

LikeLike

LikeLike

I read the title of this article literally: i.e., “War as Art,” and as I said above, I do not consider wanton destruction “art.” I did not read the title of this article figuratively: namely, as “Art about War. Of course, one can paint a picture or carve a sculpture, or sing a song about any subject whatsoever. But war creates nothing but rubble, and I do not consider blasted buildings and burnt corpses “creativity.” Union General William Tecumseh Sherman put it well: “War is cruelty, and you cannot refine it.” I do not consider deliberately inflicted cruelty “art.” Coud a painting about an act of cruelty qualify as art? Perhaps, but I would rather consider that sort of thing as a recruiting advertisement for witless barbarians or deliberately impoverished serfs promised part of the loot for sacking a city, say like Rome or Bagdhad.

Speaking of which, I did a little Internet search the other day and found a picture of U.S. marines in 2003 tying a cable around the neck of Saddam Hussein’s statue and attaching it to a tank so that they could topple it from its pedestal. I also found a picture of a painting depicting naked Visigoths putting a rope around a carved marble statue in ancient Rome so that they could pull it down and smash it. (I sent you copies of the images via e-mail) Something about the juxtaposition of the two images seemed to ring a loud, clanging bell of recognition in my head. Life imitating Art, American style. Now you know why I refer to the U.S. military as “our Vaunted Visigoths.”

Speaking of the U.S. sacking of Baghdad in 2003, I specifically remember reading of how the local Iraqis saw our invasion and ruination of their capital city. They compared it to the Mongol Sack of Baghdad in 1258. One can find lots of paintings about that disaster. Not too many of them done in the spirit of celebration. I’ll never forget seeing televsison pictures of thieves looting Iraq’s National Museum of priceless treasures while the U.S. troops stood around with their thumbs up their butts looking even more stupid and confused than usual. Then Secretary of War Donald Rumsfeld put the icing on the cake when he blew off the cultural debacle as “some kid with a vase.” So there we have a perfect example of barbarians, then and now, them and us, captured in photographs and on canvas. By the viewer’s reaction to them one can easily discern the level of civilization that he or she has attained.

LikeLike

Some kid with a vase — truly the words of a vulgarian — and a barbarian.

Yes — I didn’t write this in the spirit of “war as art” — but war as artifice — war as spectacle — war as representation — and if we think of war in that way, can art theory and advertising practices shed some light on certain aspects of war, in this case war, American-style. That was my goal.

I see war often interpreted far too narrowly, e.g. as the continuation of politics by other means, or war as just simply killing. War is political, war involves killing, but it is often much more than this. War is incredibly complex, a force that gives us meaning, to quote Chris Hedges, and what I was attempting to do here was to plumb the depths of war’s meaning, in a way I hoped was suggestive and provocative.

LikeLike

I think you did a splendid job on your essay! Though you took a swipe at my profession – well deserved! – I think you’re onto something for a future essay.

Firstly, you may be confusing advertising with ‘public relations’. I’ve been familiar with Edward Snowden’s ex-employer for 40+ years, Booz, Allen, Hamilton. Talk about schemers! They never sold shirts & cars, but know how to destroy something, or someone, for an outrageous price. (So does John Podesta, but he’s not as savvy; thus it blew up in his face.)

Secondly, mention must be made of the MATERIAL gains war always hopes for. Our old colonists weren’t shy: England, France, Netherlands, yet Amerika’s recent “spreading democracy’ blah, blah, seems to only find a need for it in resource rich places. At least our forerunners were more honest!

The out of the blue attack on Qatar (annual per capita income: $76,000) Or is it $130,000? I’ve read.

A 5* airline, not leased, but BOUGHT, and “don’t bother me with costs” international TV & internet Al Jazeera, plus a HUGE sovereign fund (355Billion$?)

I had no idea sponsoring terrorists could be so profitable! lol

LikeLike

You probably know already, that the hyper religious owner of Wolly Nobby (or something similar), the one who would fire female staff who would dare to wish to use contraception – was just found to have purchased countless plundered Iraqi artefacts in the UAE, after which he smuggled them into the US camouflaged as ’tiles’ or ‘business samples’. They were ment to end up in his ‘Museum of Christianity’, supposedly as examples of the origin of christianity …

LikeLike